Small children are astoundingly flexible visual readers – they can take in packed scenes just as easily as bold, simple images; they can follow adventures in silhouettes against bright backgrounds and turn without a flicker to the comic-like abstractions of Mr Men. This openness is on a par with their acceptance of magical transformations, upside-down houses and flying through space, and their tendency to anthropomorphise everything, from rabbits to trains and from dinosaurs to umbrellas. They know no boundaries. They also linger over pictures, with a time-defying immersion that grown-ups tend to lose.

The variety of picture-language for early readers has been brought home to me by two new books. Julia Eccleshare's brick-like treasure-trove, 1001 Children's Books You Must Read Before You Grow Up (Cassell) is arranged by age groups so that the first sections, 3+ and 5+, deal primarily with picture books, but even the later sections remind us how vital good illustration has proved over the ages. Complementing this, the large – and sometimes too brightly coloured – compendium, Illustrated Children's Books (Black Dog), offers a quick survey of great children's illustrators of the past, before concentrating on about 20 artists since 1945, including newer talents such as Mini Grey, Polly Dunbar and Emily Gravett. The entries are full of small, suggestive details, mentioned in passing, that spark thoughts about how the imagination works. I didn't know, for example, that Jan Pienkowski's signature silhouettes were based on traditions of paper-cutting and embroidery from his Polish childhood; that Quentin Blake, like John Tenniel before him, was an illustrator for Punch; that Peter, in Ezra Jack Keats's The Snowy Day, was inspired by a photo of a young black boy he had cut out from Life magazine 20 years earlier – "a photo he had kept pinned to his studio wall without knowing why".

Appropriately enough, the prefaces are written by the two children's laureates who are illustrators: Quentin Blake introducing 1001 Children's Books and Anthony Browne providing a foreword to Illustrated Children's Books. Blake explains that he moved from political satire to book illustration because he wanted to take drawing beyond the world of jokes into a realm that could embrace narrative and organise sequence and placing. It is bracing to read his quick note on all the things an illustrator has to bear in mind, from identifying with the characters, whether they are mewling infants, giants, witches, or assorted "crocodiles, dogs, mice, monkeys, goats, elephants and insects", to the technical requirements. Where in the text should a picture fall? What role will colour play? What will the readers' reaction be? And even "what implement to draw with (there are a lot to choose from)". Behind apparently spontaneous images lie deep thought and hard labour.

Experts distinguish between "illustrated books", where the picture complements the text, and "picture books", where the pictures come first. But in reality the two often overlap, and words and pictures cast a combined spell. The relationship is subtle, and the role of the artist varies. Some are supreme individual storytellers in pictures, such as Raymond Briggs or Maurice Sendak, but as well as creating their own books many artists act as illustrators for other writers. This has given rise to notable partnerships: Roald Dahl and Quentin Blake, Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin, Alan and Janet Ahlberg, Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler. And while some illustrators have an instantly recognisable style, others, such as Helen Oxenbury, are almost chameleon-like.

Credited with introducing board books for babies, Oxenbury has her own series about a boy called Tom, but as an illustrator for more than 40 years, she cannot be pigeonholed. Her work seems to spring directly from each text, whether it be Edward Lear's The Quangle Wangle's Hat, Michael Rosen's We're Going on a Bear Hunt or Trish Cooke's So Much. (I should confess here that my small granddaughter asks for these three books so often that I sometimes hide them as an act of mercy to myself – but to my shame I have only recently noticed that the illustrator is the same.) Good pictures do more than complement the text. They enlarge and widen its reference, even providing readings that the author never expected. When he wrote Bear Hunt, Rosen has said, he imagined a line of kings and queens setting out to hunt – but Oxenbury created an ordinary family, squelching through mud, tiptoeing into the cave, dashing back under the bedclothes. The final, wordless image, of the bear trotting by the sea, a lonely figure in the dusk, is all her own.

Small children don't think of characters or settings as being invented: Charlie and Lola, the Little Princess and the Gruffalo simply are. And children possess stories in their own way too. As listeners they pooh-pooh the laws of narrative. They rush ahead, or stop maddeningly at a single page and refuse to continue. Often this page involves sudden chaos or disorder, like the joy of knocking down a tower of bricks. In Judith Kerr's Mog the Forgetful Cat the favourite picture is not the climax where Mog surprises the burglar (although that allows for a bloodcurdling "miaow"). Instead the choice is Mog's sudden appearance at the window which makes Mrs Thomas jump so that the peas in her saucepan cascade to the floor. Similarly, in Lynley Dodd's Slinky Malinki, the stopping-point is the picture of the felonious cat entangled in all his purloined goods, with milk-bottles crashing and alarm clocks screeching.

In John Burningham's Mr Gumpy's Outing the illustrations build up with the rhythm of music, but the most-loved page is the great double-page spread where children and animals tumble – splash! – into the water. The chaos is resolved by a later spread, showing Mr Gumpy's passengers dry and warm, enjoying a lavish tea. Six out of 10 books (often involving animals) seem to end with "and they all had tea" and of course a birthday tea tops them all. It is rather pleasing, therefore, that the tea party we remember best is the anarchic Mad Hatter's tea party in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. But any ritual can be disrupted in a children's book. In Judith Kerr's The Tiger Who Came to Tea, the tiger eats and drinks everything in the house, nicely defying the rules tidy children long to break about "only one cake" or "no more juice". But this great beast with his slanting smile has an added power. He somehow harks back to the fatal fascination of the charming, mysterious stranger, like the devil in ballads and fairytales who arrives without warning and disappears with equal suddenness, and who is longed for as well as held in awe. The Tiger is the opposite of Kerr's bumbling domestic cat; it is her anti-Mog. In Illustrated Children's Books, she is quoted as joking that she couldn't draw tigers: "Look at the tiger in The Tiger Who Came to Tea, it's not a tiger at all." Aha, well what is it then?

Unexplained elements and out-of-scale drawings lend edginess to the cosiest stories. The chaos can be internal, and in picture books loneliness, fear, bad dreams, anxiety about separation all find their visual analogues. The scrumbly watercolour sketches of Shirley Hughes's Dogger, where the much-loved toy dog is accidentally sold at the jumble sale, express the ache of childhood loss and the joy of return, as well as complex relations between siblings, while Anthony Browne's blend of the surreal and the everyday in Gorilla suggests how imagination can fill a lonely world. All Browne's work is full of hidden clues, "images which tell us part of the story that the words don't tell us," he says, "and kids are far quicker to spot these details than adults who often take the pictures for granted."

The emotion-powered picture book currently under the spotlight, in view of the new film adaptation, is Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are. As Michael Rosen says in 1001 Children's Books, this is a fable about anger and trying to control our demons – having a wild rumpus, or leaving them behind – which also contains a profound ambivalence about the person who loves us the most. In the book, whose "text" amounts to nine sentences, all is expressed suggestively rather than directly, through the pictures. Illustrated Children's Books quotes Sendak's own response, in his book on an earlier illustrator, Randolph Caldecott. "What interests me is what children do at a particular moment in their lives when there are no rules, no laws, when emotionally they don't know what is expected of them. In Where the Wild Things Are, Max gets mad. What do you do with getting mad?" We never know why Max has been banished to his room, but it makes us think, as Rosen says, "about how we live and how best to love our children".

Sendak is a master of rage and escape, yet his errant children come back to the world of rules, meals and bed-time: when the forests and seas vanish Max finds that his supper is "still hot". Even in the surreal Mickey in the Night Kitchen, Mickey swoops back from his adventure to find that the milk is still on the doorstep in the morning. Many children find this book, with its chant of "Mickey in the batter!", far scarier than Wild Things, perhaps because it conjures up the uncanny fears of fairy stories. Both books draw their power from unresolved issues and hidden tensions, and one can see why they provoke obsessive interpretation. Some readers, I learnt from these two surveys, have apparently labelled Mickey's nakedness as "obscene", while other critics argue that "the book has too much sexual symbolism – the phallic milk bottles, fecund batter and sloshing liquids". This last point might be right, but much is lost in the analytic retelling.

Interpret their power as we may, images from children's books are now omnipresent, flitting from books to cartoons, films and toys. Indeed it is hard to imagine childhood without them. The demands on space in 1001 Children's Books and Illustrated Children's Books mean that, while individual entries are vivid and informative, the broader historical coverage is perfunctory – a pity, since it is a fascinating tale. What did children look at before the advent of illustrations? The richer ones could pore over woodcuts and copperplates embellishing fine editions of Aesop, or follow the tales in tapestries and paintings, but most children made their own pictures in their minds as they listened to stories and ballads, or made do with rough woodcuts from the chapbooks. John Clare remembered that he had learnt most from the psalms and the Bible and from the "sixpenny Romances of Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, Zig-Zag, Prince Cherry", and so on.

These chapbooks, a staple of the peddlers' packs, were really intended for adults: the first book identified as specifically for children was Comenius's educational text, Orbis Sensualis Pictus, translated into English as The Visible World in 1659, with 150 woodcuts. But it was not until the mid-18th century in Britain that children's book publishing really began, prompted by the fashionable belief, influenced by Locke and then by Rousseau, that learning should be fun. The old horn books were replaced by fold-out alphabet games and "lotteries" with sheets of images to colour.

Soon London publishers such as John Newbery were producing tiny books such as the Little Pretty-Pocket Book, the size of a child's hand. At the same time the great French fairytales were translated into English, soon followed by the exotic Arabian Nights. These, too, appeared in children's editions, often with tiny postage-stamp pictures, like early comic strips, but occasionally with fine illustrations such as the meticulous wood-engravings of Thomas and John Bewick. Young readers could move on to illustrated versions of English favourites such as The Pilgrim's Progress and Robinson Crusoe.

With regard to pictures, then as now readers were conservative, clinging to versions they knew. Charles Lamb considered it "blasphemy" when a grand, new edition of The Pilgrim's Progress was suggested, with illustrations by John Martin, replacing the chapbook cuts he knew as a child. Lamb also objected to the evangelical educational material flooding on to the market from writers such as Anna Laetitia Barbauld and Sarah Trimmer, complaining to Coleridge in 1802: "Mrs Barbauld's stuff has banished all the old classics of the nursery . . . Think what you would have been now, if instead of being fed with tales and old wives tales in childhood, you had been crammed with geography and history." In fact these books were far less stuffy than Lamb suggests, and from the beginning illustrators often showed a sly, subversive streak, depicting children up to no good, raiding birds' nests or playing with dangerous objects in the home in a way that left little doubt that mischief was more fun than virtue.

The popularity of children's books ensured that illustrations were taken seriously. In 1807 William Roscoe's The Butterfly's Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast came out, with luscious, detailed, hand-coloured engravings; in 1809 Tabard's Popular Tales carried fluent, mobile line-drawings of characters such as Sinbad that have influenced interpretations ever since; and in the 1820s George Cruikshank produced his classic, spiky, scary illustrations to Grimm's Fairy Tales. Pictures improved with each leap in technology, the most important being the invention of lithography in the early 19th century. And although the moral tales marched on, by the 1840s they were being rocked and mocked by translations of Heinrich Hoffmann's violent and satirical Struwwelpeter, and Edward Lear's Book of Nonsense, in which the eccentric drawings, as well as the verse, undercut all solemnity. In the 1860s came the fraught and brilliant collaboration of Lewis Carroll and Tenniel in the Alice books, adding a new resonance to fantasy. The later years of the century were awash with imperial stories of derring-do, "beautiful children" such as Little Lord Fauntleroy, and eternal youths such as Peter Pan. With them came a "golden age" of illustration, the work of a stable of artists linked to the printer Edmund Evans, including Walter Crane, Kate Greenaway, Randolph Caldecott and Arthur Rackham. In their wake, the new century dawned with another highly original talent, Beatrix Potter, whose Tale of Peter Rabbit was published in 1902.

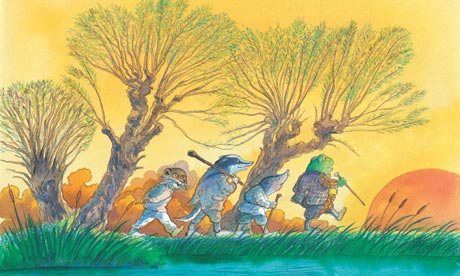

Scanning this history I feel a rising anxiety about unmentioned favourites – where is Captain Pugwash, or Orlando the Marmalade Cat? What about the great bursts of children's writing and illustration, such as the run of invention in the 1920s and 30s? In Illustrated Children's Books Peter Hunt makes a rough list from that period – "Mary Poppins, Biggles, Babar the Elephant, The Hobbit, Dr Seuss, Tarzan, Just William, Worzel Gummidge, Mickey Mouse and Superman, Desperate Dan and Korky . . . and Rupert Bear". To this one could add Winnie the Pooh, The Wind in the Willows, Dr Doolittle, Swallows and Amazons, Milly-Molly-Mandy and the pioneering interweaving of pictures and speech in the first of Edward Ardizzone's Tim series. Was this flowering a result of new markets, or was it perhaps a response to the darkness of the 1914-18 war that had blighted the lives of so many children?

Each new generation has embraced new writers and artists. And in the past 50 years, the qualities of the book as a three-dimensional object have also been increasingly exploited, from the advent of board books and textured, "feely" board to the use of cut-outs and pop-ups (a return to a device popular in Victorian nursery rhymes and fairytales). Sometimes I feel that the realm of children's picture books is the one place that "book art" – playing with a book as a visual, tactile object – has found a home in the commercial world. Children have become used to the clever slippage from page to page that Eric Carle used in The Very Hungry Caterpillar in 1969 and the Ahlbergs used in Peepo! in 1981. They enjoy the play with different forms of representation, such as the mix of photography, typography and drawing in the witty collages of Lauren Child's Charlie and Lola series. They laugh, too, at postmodern games with the constraints of page and volume, as in Catherine Rayner's new book Ernest, where Ernest the moose is too large to squash between the margins until he and his chipmunk friend manage a final, glorious fold-out.

Small readers like leafing through books, turning pages backwards, poring over pictures, throwing them down abruptly. But usually the enjoyment of books at this stage is, as Browne says, a shared experience. The power of pictures is enhanced, too, by chiming refrains or tongue-rolling rhymes: "Silly old Fox, doesn't he know there's no such thing as a . . . Gruffalo?" or "Slinky Malinki was blacker than black, a stalking and lurking adventurous cat". But 1001 Children's Books moves swiftly beyond being read to, into the intense world of private reading and imagining.

Although my subject is illustrated books for small children, the breadth and depth of Eccleshare's trawl through the literature, right up to the most demanding teenage fiction, demands noting and celebrating. The book is compiled chiefly for adults forming a child's bookshelf, but it would also be perfect – like a good library, or old-fashioned bookshop – for older, greedy-reading children to browse through to find what to read next. Within each age group, titles appear chronologically, so that one follows the development of the genre in all its variety, from myths and folk-tales to domestic stories or pirate adventures. This chronological sequence is also a bird's-eye map of the ideology of particular eras, showing how it is reinforced by writing for children, and confronting the difficulties of attitudes to race and gender in the most cherished tales – the prejudices lurking in Tintin, or the relics of imperialism in Babar the Elephant.

Illustrators have always played an important role, both in reinforcing current values and stereotypes and brilliantly debunking them. To take just one example, girls' school stories, set in the Chalet School or Malory Towers, could never be the same after the demonic girls of Ronald Searle's St Trinians rampaged into print in 1948. The figures in Searle's cartoons, notes the entry on this book, "are all angles, with sharp little expressions knotted into mischief, and not a pretty face in sight". Boys fared the same. Even the first irreverent Jennings book, which appeared in 1950, was trumped three years later by Geoffrey Willan's Down with Skool!, which Searle also illustrated. In 1001 Children's Books Philip Pullman locates its "irresistible flavour" in its misspellings and anarchic phrase-making, but also in Searle's drawings, which do not date with the text, but remain "wildly and gothically extravagant masterpieces of comic art . . . 'A Corner of the Playing Field' for instance, showing a single crow looking down from a dead tree at a bleak rain-swept expanse of mud, littered with empty bottles and cans".

A real bonus is the inclusion of titles from around the world. A young French friend pounced with fierce delight on this book, astonished that I did not know Natha Caputo's Roule Galette or René Goscinny's Petit Nicolas series; how could this be? As she explained with passion what it was like to grow up surrounded by bandes dessinées, the graphic stories that have reached our shores chiefly through Tintin and Asterix, I realised that there is no substitute for knowing books in childhood, as a deep, unmediated way of encountering the world. Many foreign stories, like British classics, take place in that liberty-promising realm from which adults are banished or consigned to the margins.

The way that these tales highlight children's self-sufficiency (rather than their darker selves) is a springboard for a third book on my table, Jane Brocket's Ripping Things to Do: The Best Games and Ideas from Children's Books (Hodder & Stoughton). This is full of jolly wheezes and projects, from tree-houses to treasure hunts, and many of us might sigh dejectedly as we compare our failures to the Brocket family's genius for hammock-making or literary table tennis. Luckily, the gung-ho efficiency is redeemed by the author's sense of humour (her jumping-off point is William Brown taking the library clock apart "to see how it works", inspired by a Christmas present called Things a Boy Can Do), and by the selection of period line drawings. These range from Milly-Molly-Mandy's cut-out dolls to the reviled Famous Five, taking a dip in a rock-pool on Kirrin Island before "racing back to their cave for a nice hot drink and a hearty breakfast, all ready and energised for whatever adventure awaits". Those were the days.

Reading itself can feel like a well-appointed cave, a private retreat. In 1001 Children's Books, the run of introductions to individual titles is interrupted from time to time by special reviews from writers. Here the real magic of reading glimmers through. Judy Blume, for example, remembers her mother taking her to the library, where she sat on the floor and thumbed through the books. One day she found Ludwig Bemelmans's Madeline (1939) – important, I think, that it was her own discovery, not handed to her by an adult. "I loved that book! Loved it so much that I hid it in my kitchen toy drawer so that my mother would not be able to return it." Later she realised that her mother would have bought her a copy of her own, but then she didn't know that such a thing was possible: "I thought the copy I had hidden was the only copy in the whole world." This anecdote conjures up the extraordinary force of "wanting" – an emotion too direct even to be called desire – that childhood books can evoke.

We might never work out why they mean so much. In this case, Blume remembers that, while she was small and scared of everything, Madeline was equally small but always brave, and that, by reading, she could cloak herself in her heroine's boldness. It didn't matter that the Parisian, Catholic setting was remote; she surrendered without question to Bemelmans's impressionistic drawings and his opening lines: "In an old house in Paris, that was covered in vines, lived twelve little girls in two straight lines."

Illustrations – especially for children's books – used to be regarded as a lesser, ephemeral art. The first signs of change came with a few pioneering exhibitions. Now we can research early examples in the Wandsworth collection, built up after the great Osborne collection went to Canada in the 1950s. In Newcastle, Seven Stories is a flourishing centre for children's books, with an archive of artwork and manuscripts, while in London, Quentin Blake's brainchild, The House of Illustration, plans to open a permanent base as part of the King's Cross regeneration. Next year the charity Booktrust launches a second round of its competition The Big Picture, to find a new generation of children's illustrators.

Both Blake and Browne see picture books as a route to appreciating art, as well as stories. "The illustrations in children's books are the first paintings most children see," Browne writes, "and because of that they are incredibly important. What we see and share at that age stays with us for life." Eccleshare, too, notes in the introduction to 1001 Children's Books that it is often the illustrations, "absorbed in early childhood, that will rekindle the strongest and warmest memories . . . Taking even the oldest reader straight back into the essence of their own childhood." She is right. These pictures act like an evocative scent, or Proust's taste of the madeleine, thrusting us back in time. In Illustrated Children's Books Browne makes an impassioned plea for us to place more value on the skill of "learning how to look". Why do we lose the lively visual awareness of childhood, or the unembarrassed urge to draw? We should focus, he suggests, on visual as much as verbal literacy. If we learn to do this, perhaps we can, if lucky, retain the child's fetter-breaking, visionary power of the imagination, however old we grow.

To order 1001 Children's Books You Must Read Before You Grow Up for £18, Illustrated Children's Books for £22.95 and Ripping Things to Do for £16.99, all with free UK p&p, call Guardian book service on 0330 333 6846 or go to theguardian.com/bookshop