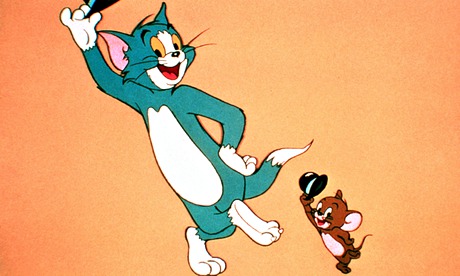

Early Tom and Jerry cartoons that feature Mammy Two Shoes, the stereotype black maid, now carry a health warning on Amazon. The animations, it warns, represent “some ethnic and racial prejudices that were once commonplace in American society … that were wrong then and are wrong now”.

Tom and Jerry join a long and growing list of old favourites that are suddenly denounced for failing the test of contemporary sensitivities. This is the cue for an argument that cuts through attitudes like a cheese wire: mirth and derision at political correctness on the one hand, and agonised uncertainty from everyone else.

It’s painful, relocating one’s understanding of stories that are old friends, whose characters and experiences permeate one’s memories of childhood. I can now see that my own favourite character, Babar, is among many other things a hero of several tales that consistently promote the superiority of western ways over African life. But as a child I wept for the motherless elephant, cruelly orphaned by wicked big game hunters, who was befriended by a charming elderly French lady he meets in Paris and returns to his homeland to introduce the ideal city, Celesteville, named in authentically colonial style after his wife.

In the general context of Mammy Two Shoes – a black, grown-up woman coexisting with a cat and a mouse locked in very human scheming – I struggle to see that the blackness of the adult and her subordinate role in the household is likely to have a profound influence on the way a child understands the world in which she lives. Yet I was once brought up short by evidence of how books shape perceptions. Years ago, trawling through a friend’s extensive collection of 1950s Ladybird books (I loved the history tales, and can still see Alfred’s horror at the burned cakes), my small daughter found one about becoming a doctor that featured only men. She read it avidly, but as she put it down she asked sadly, “Does that mean only boys can be doctors?”

So I don’t have a problem with the list of children’s favourites that are now gone (Little Black Sambo) or have been rewritten like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, where the Oompa-Loompas had to be reimagined twice to fit Roald Dahl’s own changing perceptions, although he never quite expunged the idea that it was acceptable for one group of people to dehumanise another. I recognise that Asterix has some unfortunate scenes and am relieved that Tintin in the Congo came to embarrass even its author.

But I struggle with the criticism of books written in the heyday of western imperialism. From The Secret Garden to Doctor Doolittle to Sherlock Holmes, I can see that they are a mortifying embodiment of late 19th-century attitudes to people who are not white Anglo-Saxons. But most 21st-century children can accommodate the absence of indoor servants and gardeners in their lives. They can be trusted to see that relations between people have changed too.

Maybe the recurring outrage about old stories is actually a reflection of a different problem. As the children’s laureate Malorie Blackman argued earlier this year – triggering abuse exceptional even by the inflated standards of Twitter – there is still not enough diversity in children’s books, not enough interest in other cultures, or different perspectives.

If children and their families could, sometimes at least, find stories that reflect their own experience of life, across all cultural forms, then the dated attitudes of old classics could be safely seen as just that.