The man behind the counter in our local dry cleaner's is a tireless optimist. "Me, I think they're alive," he said on Tuesday, handing over some freshly pressed shirts. "I think they're somewhere we don't know about, somewhere secret." Wherever they were, he hoped it would be safe and warm there, and that they had enough to eat and drink while they waited to be rescued. He smiled; his was a well-meant thought – for the previous ten days the friends and relatives of the 239 people aboard flight MH370 must have wished the same thing, only a thousand times more intensely and through every waking hour. I said it would be a wonderful outcome, but of a kind that happened only in fiction. In fact, that isn't quite right: in 1972, 16 passengers survived sub-zero temperatures in the Andes for 70 days, long after attempts to locate their missing plane had been abandoned and their chance of survival written off. Piers Paul Read told the story of their immense courage and resource, which included feeding off the bodies of their dead friends, in his celebrated book, Alive. But it was a different book I remembered in the dry cleaner's, and one written not many miles from where we spoke.

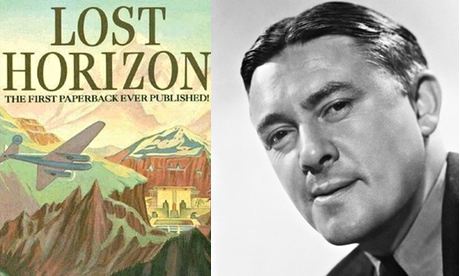

James Hilton finished his novel Lost Horizon at a house in the east London suburb of Woodford Green in April, 1933. It won the Hawthornden prize in 1934, but only began to command popular attention after Hilton published his next novel, Goodbye, Mr Chips, in the same year. Chips had taken him only four days to write – it's no longer than a longish short story – and nothing about its subject matter suggested mass appeal: on the edge of retirement, a teacher in an English public school looks back on his career, his marriage and the boys he has taught. But it had the most extraordinary success – actors as various as Robert Donat, Peter O'Toole, John Mills and Martin Clunes have all played Mr Chips in film and stage versions – and it created an appetite for Hilton's work that Lost Horizon stood ready to satisfy.

By the 1940s, one or both titles had found a place on most British bookshelves, yet in terms of setting, structure and narrative, no two novels could be more different. What joined them was an atmosphere of loss, a saccharine kind of wistfulness and a longing that the dead hadn't died, or that they might be met again, which in the wake of the first world war was a mood that suffused Europe and its empires. There was, you might say, a lot to be wistful about.

Lost Horizon's story begins with an aircraft that disappears mysteriously in the east; nobody knows why or how, apart from the flight's four passengers, a few of the white residents of a troubled colonial outpost on India's north-west frontier who stepped aboard believing they were being evacuated to the comfort and safety of Peshawar. The pilot turns out to be a hijacker – perhaps even the first hijacker – and flies them instead over the Himalayas and into the mountains of northern Tibet, where mountain guides meet them and offer refreshments in the form of perfectly ripened mangoes and delicious wine ("not unlike a good hock"), before leading them along vertiginous paths to their near-inaccessible destination, which is a lamasery above a valley called Shangri-La.

Like Mr Chips, the word has become part of the English language, the name of retirement bungalows from Devon to Durban; of hotels and boarding houses promising rest and seclusion in every continent; of a county in the Chinese province of Yunnan (renamed from Zhongdian in 2001 to promote tourism); of an American aircraft carrier; and of Franklin D Roosevelt's presidential retreat (since renamed Camp David). The imagination of what his critics knew as a "middlebrow" novelist made all this possible, rather than oriental scholarship or the worship of holy men. Hilton was born in 1900 in Leigh, Lancashire, and died in 1954 in Long Beach, California. The son of an elementary schoolteacher, he was an occasional contributor to the Manchester Guardian before he became a novelist. I like to think of his typing fingers tapping out the name Shangri-La for the first time in a house on the edge of the Epping Forest, with no suspicion of the effect it would have on global nomenclature, the threat it posed to "the Pines" and "Bon Accord" and "Sea View".

In the book, what Shangri-La promises in its isolation is a harmonious and immensely long life. It has flush toilets and comfortable baths imported from America, but is otherwise "uncontaminated" by dance bands, cinemas and neon. "Your plumbing is quite rightly as modern as you can get it, the only certain boon, to my mind, that the east can take from the west," the most sympathetic of the hijacked westerners tells his hosts. "I often think that the Romans were fortunate; their civilisation reached as far as hot baths without touching the fatal knowledge of machinery." But the real mark of Shangri-La is its avoidance of any kind of excess. The people are "moderately sober, moderately chaste, and moderately honest". According to its visionary head lama, the sanctuary is the equivalent of a Noah's ark that will preserve human values through the age "when men, exultant in the technique of homicide" destroy the world beyond. "Then, my son, when the strong have devoured each other, the Christian ethic may at last be fulfilled, and the meek shall inherit the earth."

In a western world that was recovering from one world war and beginning its march towards a second – Nazi Germany passed its first anti-Jewish laws in the month the book was finished – the idea of a mountain utopia held a powerful appeal. Of course, it was fiction: no sane person took it as anything else. Nevertheless, it was a more believable fiction then than it would be today, because in 1933 the physical world was still not entirely known. Mount Everest had defeated several expeditions; few westerners had seen the remoter parts of Tibet. Mysteries provided a staple of pub and playground debate. What could have happened to the steamship Waratah, which vanished with its 211 passengers and crew off the South African coast in 1909? (No trace was ever found.) Could Colonel Fawcett and his son Jack still be alive somewhere in the unmapped jungles of Brazil? (They'd last been seen in 1925, setting out to find a "lost city" that he called "Z".) The world was still big enough to get lost in and never be found: to disappear wasn't as it is now – an offence against technology, an impossibility, an outrage.

Lost Horizon also ends with unknowns. Of the plane's four passengers, how many still live? And does the most sympathetic, the protagonist Conway, return to Shangri-La after his brief visit to a world bent on its own destruction? We don't know, though as readers we know more than any other character in the book, apart from Conway and the narrator. "Never reached there [Peshawar] and never came down anywhere else, so far as we could discover," says a fellow pilot. "I suppose they all got killed, somehow. There are heaps of places on the frontier where you might crash and not be heard of afterwards."

How good it would be if the passengers on flight MH370 could disobey the same kind of commonsensical reasoning and have a fate like Hilton's characters. That they should be alive in the kind of place that used to be called "a fastness", eating perfectly ripened mangoes, drinking rather good hock, and waiting for the spotter plane to find the SOS that they've marked with white rocks on a green hillside. But it seems that the world has grown too small for that possibility.