About a year ago I received an unsolicited package from France addressed in an oddly familiar, spidery hand. It was from Ronald Searle, and contained a box of pens he had bought in 1963 and had found at the back of a cupboard.

In the attached note (along with a scrap of file paper on which he'd done some doodles to check the nibs) Searle said he thought I'd like them as he had quite enough pens to see him out. For any British cartoonist this was the equivalent of being given a high-five by God.

Roughly a year earlier Searle had given Steve Bell a box of pens (either before or after he drank Steve under the table) during a visit to Searle's home in France to prepare for a 90th birthday retrospective at the Cartoon Museum, requesting they be passed on to me.

Perhaps it was my effusive letter of thanks that made him think of me again; perhaps he was just clearing out some clutter and, ingrained with the kind of thrift you learn during three years as a Japanese prisoner of war, could never throw away something someone else might want. Either way, I felt like Cruikshank must have done when he was given Gillray's old drawing table.

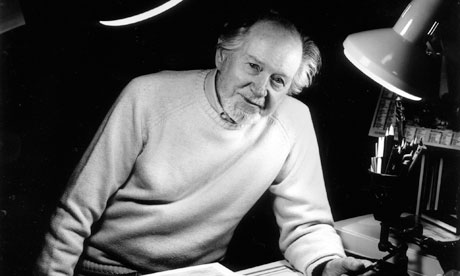

Searle was, after all, easily the greatest cartoonist of the 20th century. Professional since his teens (though just a townie schoolboy, he got commissioned by Eric Hobsbawm to draw for Granta in Cambridge in the 1930s), in the decade following the war he managed, with St Trinian's and Molesworth, to weave himself into the DNA of the nation.

It is interesting to note how men of Searle's generation – Spike Milligan being another notable example – translated the unimaginable trauma of the war into stuff like St Trinian's or The Goon Show. And how distinctly unsettling it is to when you look at the drawings he produced in secret on the Burma Railway, and then see direct visual quotations of torture and beheadings in his later St Trinian's cartoons.

Even if most Britons will remember him as 'the St Trinian's cartoonist', Searle was much more than that. Without him, it's almost impossible to imagine cartoonists like Scarfe or Steadman or the subsequent generations inspired by them.

In 2005 I presented a BBC4 documentary on Searle in which I did some drawing in his style, trying to capture the peculiar magic of his defining blotchy, beautiful, raggedy, cross-nibbed "line". When I got it almost right I recognised something else: other cartoonists (myself included) can twist a nib just so to snag on the paper and release a spatter of blots that invariably denote blood or shit. But when Searle did it, they were champagne bubbles. With a supply of the master's nibs, maybe one day I'll pull off the same trick.

Martin Rowson is a cartoonist for the Guardian