If you’re a woman who has been made to feel a little slovenly and neglectful this week by the realisation that you haven’t had your uterus steam-cleaned, you might have been prompted to wonder whether you will ever reach a stage of life when you can stop being told your body is disgusting and finally find yourself acknowledged for other qualities, such as your character and achievements. When you’re dead, maybe?

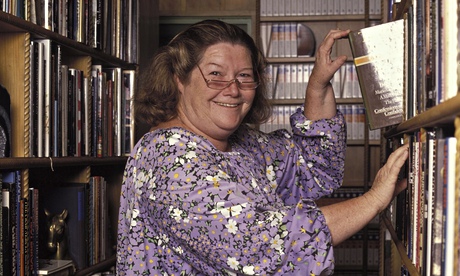

I’m afraid not. Last week, we learned that, even when you’re no longer here to care, you will still be judged for what you looked like and whether anyone fancied you; at least, according to the obituary published in the Australian for the bestselling author and neuroscientist Colleen McCullough, who died aged 77.

“Colleen McCullough, Australia’s bestselling author, was a charmer,” it begins. “Plain of feature and certainly overweight, she was, nevertheless, a woman of wit and warmth.”

It’s not exactly what any of us would hope for in the opening lines of a tribute about our life’s work, particularly if that work had included two highly successful and demanding careers. It’s that “nevertheless” that does it; pitched somewhere between sneering and pity, it makes the unspoken assumption that you wouldn’t usually expect an unattractive woman to possess a lively mind or be appealing company. Despite the massive disadvantage of her appearance, the writer is saying, she managed to be likable. He probably imagined this was a compliment.

If McCullough had made her fortune and career as, say, a couture model or a Hollywood star, despite not meeting the expected standards of female presentability for those professions, there might, at a pinch, be justification for making reference to her appearance. But she was a novelist. An extremely successful one. She wrote 25 books, of which the best-known, The Thorn Birds, sold more than 30 million copies. Before turning to fiction, she ran neurophysiology departments and research labs. You don’t need to be beautiful to do any of those things; you do need a number of other abilities that are apparently of less significance to a male obit writer.

Yes, but that’s the Australian, you might say. They used an outdated obit whose author has himself since died (I’d like to think his obituary began: “Stunted of imagination and certainly envious, he nevertheless scraped a living writing unsigned lists of other people’s achievements”). But this is not an isolated incident. We see it everywhere now, this idea that it’s reasonable to judge a woman on her appearance first, regardless of her talents.

We see it when a male TV critic feels entitled to judge a female historian on her looks rather than her knowledge. We see it when a male sports commentator casually remarks that the Wimbledon women’s champion will “never be a looker”. We see it every time Hilary Mantel upsets a conservative newspaper, in the malicious asides about her appearance. It’s there whenever newspaper commentators direct their objections at a female writer’s face rather than her arguments.

In one of those spontaneous eruptions of humour as a corrective to offence that shows Twitter at its best, the first WTF? responses to the Australian’s obituary quickly evolved into the hashtag #myozobituary. Male and female users jumped in to imagine what their own death notices would look like according to the Australian’s template. “Short, an indifferent housekeeper who admitted she never exercised, she nonetheless married twice and wrote numerous books,” wrote the feminist author Katha Pollit. “Although his beard looked like someone had glued it on and his hair would have been unconvincing as a wig, he married a rock star,” said Neil Gaiman.

By all accounts, McCullough enjoyed a joke; it’s nice to think she would have appreciated this response by those outraged on her behalf. But what’s needed is a broader shift in attitudes; a determination on the part of the mainstream media, in the first instance, to speak about women in the same way they talk about men: in terms of their abilities, their achievements or their character, and leave their looks out of it. Then we might be able to celebrate publicly a scientist, an author or an athlete without belittling her at the same time.