Arthur Conan Doyle

It would be wilful not to make Holmes number one. What we’re after here is sleuthing, not thriller-cop-hero stuff, and the fact that Holmes is just about to feature in his zillionth film (starring Robert Downey Jr, left) shows our rolling-generation fascination with the ability of those who can see what others cannot. Or, when all can see, can bring inferences and deductions that our smaller brains cannot. Sherlock, most brilliantly realised by Benedict Cumberbatch and his writers, has been an intellectual delight. And winningly, humanly, he gets things wrong Photograph: Alex Bailey/Warner Bros.

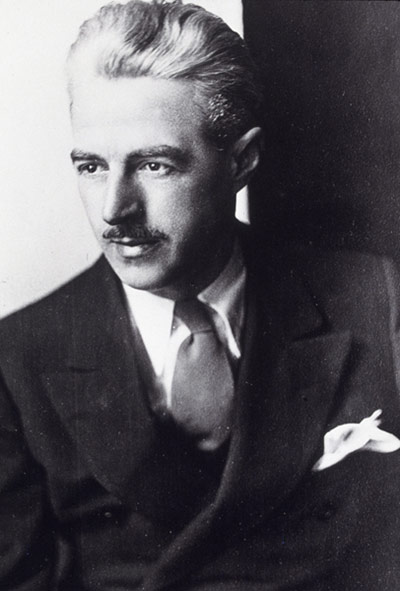

Dashiell Hammett

I’ve gone for this Man With No Name rather than Philip Marlowe and his unbeatable one-liners because, evocative though Raymond Chandler’s antihero is, Marlowe too often shot first and asked questions afterwards. Hammett (pictured) gave us a wise and ego-free sleuthing flatfoot, who follows up and follows up and, rained on and cold and tired, keeps following up tiny matchbook leads until he has done his paid job. True sleuthing in Red Harvest and The Dain Curse and we never knew his name. To make up for this, Hammett gave us Sam Spade Photograph: SNAP/Rex Features

Jeffery Deaver

The Bone Collector and its successors shocked and fascinated. There have been many fictional forensic scientists, but Deaver, whose latest job is to write the new Bond book, gave us a tetraplegic black expert, who’d been crippled by a girder-fall during a crime-scene investigation. Rhyme has a male nurse, one working finger, a tetraplegic-compatible computer, an encyclopaedic knowledge of the archaeology of Manhattan and a brain which, like Sherlock’s, connects in the oddest and most wonderful way. Dark and joyous Photograph: Columbia Pictures/Allstar Picture Library

Colin Dexter

There are too many TV cops, yet Morse endures. He does so because he’s not just using “the procedural” – a point so winningly emphasised in his interplay with superiors – but brains and hunches. In Morse’s case – perhaps fortuitously, what with him living in Oxford – he has what we call the “benefits of a classical knowledge”, coupled with a fine distrust of humanity and of himself. Again, it’s sleuthing, it’s leaps, it’s sudden synaptic jumps that work. It’s his hearing Lewis burbling on about some Lloyd Webber dirge, and drifting into thoughts of opera, and making the connections Photograph: ITV

Martin Cruz Smith

Renko, who first appeared in Smith’s blockbuster Gorky Park, doesn’t just have to sleuth his way through impenetrable riverside murders in filthy, frozen, rush-strewn marshes: he has to sleuth his way around the dying communist state and its quadruple-bluffing, its omnipotence, its reworking of evidence, its falsity. And it’s all terribly cold and there are everywhere drink and memory problems. Even Sherlock would have given up. Renko persists. A very Russian fable of a good man beset by all. Written by an American Photograph: Allstar

Harry Kemelman

The finest crime short story I have ever read is The Nine Mile Walk. There are no heroics, simply logic and deduction. Nicky Welt isn’t even a sleuth – he’s a professor of English with a special interest in logic. He and a friend argue over whether a series of deductions can be logical and yet not be true. Welt asks for an utterly random sentence from his friend. “A nine-mile walk is no joke, especially in the rain,” is given and accidentally overheard. A series of logical inferences becomes a concrete suspicion, then a tentative telephone call to the police and arrests. Utterly inspired Photograph: Public Domain

Peter Hoeg

Smilla’s Sense of Snow was the film version of Hoeg’s book, Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow and no, I don’t know why either. Anyone who has read it knows it goes, frankly, mad at the end. Loopso, actually. But the opening chapters, in which Smilla works out that a young boy’s accidental, snowy roof-fall death was far from an accident – and works it out by just knowing, having been brought up in Greenland, the difference between 17 kinds of ice crystals – and thus sets in store a pocketful of woes, is as sleuthy, as minorly and beautifully detailed as will ever happen Photograph: Allstar

Ian Rankin

The Americans have heroes or antiheroes. Here, we have something in between in both Rebus and Morse, who share a human middle ground where they can’t quite decide whether they want to be hero or antihero. But both are sleuths – more so than Poirot and Marple, who always failed to resonate for me, mainly because those things didn’t even come close to happening. Rankin’s Edinburgh is as true as it gets. Jack Rebus sits in the Oxford Bar, trying to be Scottishly unbotherable and unbothered and suddenly gets the connection. Black and Blue is his finest Photograph: ITV

Umberto Eco

Brother William, as portrayed by Sean Connery in the (fabulous) film adaptation of The Name of the Rose, is perhaps the luckiest of our sleuths. He gets to solve one of the most ancient mysteries of all – the mystery of laughter. Eco has brought us not just the idea of a dedicated monkish sleuth, but the idea of a high private library, in a private high tower, from which the last investigator had been thrown. The sleuthing – this is not about men with guns, but men with brains – revolves around ancient texts, and men with a hatred of laughter, and is as intriguing as it gets Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext Collection/Sportsphoto/Allstar/Cinetext Collection

Frederick Knott

Dial M for Murder, the film adaptation of Knott’s stage play, is Hitchcock’s finest. Hubbard is played by John Williams in a cast that mainly features Ray Milland and Grace Kelly. Milland plots to murder his wife for her inheritance, but then his hired blackmailer burglar/murderer is killed. Milland smooths it all out, but Hubbard is several steps ahead. What follows is complicated, but involves Hubbard deducing where Milland will look for a second door key, based on what his hired dead blackmailer might have done and – ta-da! Sometimes you just yearn for Hitchcock and Knott still to be alive Photograph: Public Domain