The term “manga” comes from Katsushika Hokusai’s books of “random images” published in the early 19th century. Now, 200 years on, the genre has exploded into something much wider. Somewhat like the Franco-Belgian bande dessinée or the US comic strip, the Japanese manga covers a range of topics, from politics to social criticism, retellings of classic stories to everyday escapism. Above all, though, it’s about how to live in Japan’s contemporary megacities, places that are some of the most advanced on Earth, yet also sites of decrepitude, with friendly people and excellent social services, but also alienation and the disappearance of children in a fast-ageing nation.

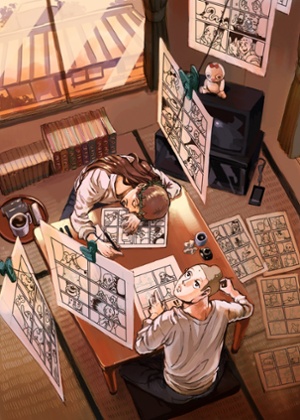

The British Museum exhibition Manga now, which opened on Thursday, focuses on three makers, and while the majority of manga have texts, this selection concentrates on images alone – perhaps this is wise given that few visitors will read Japanese, and the texts are laden with jargon and in-phrases. The three makers are all alive today, but span the postwar era. Tetsuya Chiba, born in 1939, explores the figure of the striving individual, often a sportsman, with a piercing stare into the future. Yukinobu Hoshino, 15 years younger, is represented by his alter ego, Rainman, a split self inhabiting a twilight world, half-Tokyo, half-graveyard. Hikaru Nakamura, still in his early 30s, riffs on manga history in a postmodern way, showing Christ and Buddha as teenagers drawing (or dozing over) manga at a low Japanese-style table. It’s interesting to see how the work is very Japanese but the characters are given mixed-race features.

Perhaps the main way in which manga differs from its western equivalents is that it’s taken seriously as art. It is not just the content that is important – though of course that’s part of it – but the signature style of the artist. If you can, go and see for yourself.

• Manga now: three generations is at the British Museum, London WC1, until 15 November. britishmuseum.org.