As a young man, PJ (Patrick Joseph Gregory) Kavanagh, who died this week, went to Ireland and sought out the celebrated poet of The Great Hunger Patrick Kavanagh. Finding his bibulous namesake in a hostelry, he introduced himself. The old poet said: “Why don’t you change your feckin’ name,” and settled back to his gloomy pint.

PJ’s father, Ted Kavanagh, wrote comedy, notably for wartime radio, It’s That Man Again (ITMA). When Ted was around, the house resounded with the clack and ping of the typewriter. “He lived by writing jokes and had a sort of quasi-rebellious attitude to society as anybody who makes fun of things does.” PJ did not live by jokes, though he could be hilarious company.

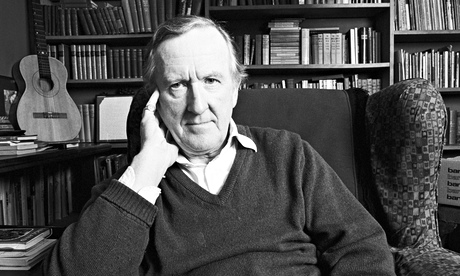

PJ addressed me as his “Dear Sedate Publisher” because I published not only his poetry but his essays and seemed untroubled by the rate-of-sale. Born in 1931 and raised in London during the war, he had seen a lot of the world and suffered significant early loves and bereavements. The latter (particularly the sudden, early loss of his first wife Sally to polio, recounted in his classic memoir The Perfect Stranger in 1966) “must relate one to other people – rather than separate one from them”. He was a soldier (Korea, wounded), a disaffected student at Merton College, Oxford, an employee of the British Council in Indonesia, a broadcaster, actor (emerging with David Frost and Willie Rushton, including in his later credits Half Moon Street with Michael Caine and Sigourney Weaver, and the part of a Nazi priest in an episode of Father Ted), a memoirist, poet, essayist and critic, a nature writer rooted in his beloved Gloucestershire but able to see beyond its borders, an anthologist and editor.

He knew the value of what he wrote and that, like the quiet, formal, questing work of Edward Thomas and Ivor Gurney (which he edited and revived), it would find a place. Life taught him that irony inheres in how the world treats us, what it gives and snatches back: it is an aspect of his themes, not of his style. This and his Catholicism set him apart from his ironical contemporaries, though Philip Larkin might almost have agreed that “Every response to a poet, or more specifically to a poem, is in a sense autobiographical. The work appeals to, or coincides with, some part of our own nature, or perhaps to some deficiency of ours, of which we are aware, and it supplies some lack.”

He did not like to be called a nature poet. In the poem “Nature Poet” he speaks of himself in the third person: “He liked all the people he could and, more than is normal, / Cherished his dead, thought often of them, because they were still.” He detects mercy, “Wafting, as though remembered.” This is religious elegy of a high order, having more in common with George Herbert and Gerard Manley Hopkins than John Clare and William Wordsworth. Kavanagh wrote of “a sense of two worlds: of us living simultaneously not just in this world, but in another too”. He tells transcendent truths without the fibbing one can get in Yeats. In “Resistance” (watch the commas) he evokes

A bridge of punctuation angels use

To balance on, when, soft as feathers

Stroking our dismay, they tell their weird,

Without complacence, grief-including jokes,

And sigh, at our resistance.

PJ followed Patrick Kavanagh’s advice and changed, or abbreviated his name. He found his own ground, his own great hunger, and in a tentative faith rooted in particulars, a way of transcendence. There is an old cat in a late poem who is about to die. He imagines her going to his dead beloved in the other world, moving against her legs.

Warm and dry it alights, almost

weightlessly, and

as light and as dry as this trusting

bird on my finger

the weight of your hand curved

round the back of my hand

I suddenly remember.