It’s an axiom of travel writing that, if n represents the discomfort endured by the writer, 10n represents the pleasure enjoyed by the reader. Look at the perennial appetite for the stories of Scott and Shackleton, who battled unimaginably hostile conditions in their searches for the South Pole. Not for nothing did Apsley Cherry-Garrard, a member of Scott’s expedition, call his book The Worst Journey in the World. In 93 years, it has never been out of print.

Sven Hedin, a Swedish explorer born in 1865, is not nearly so well known. But his sufferings were just as acute, and his memoir, My Life as an Explorer, is a fascinating period piece as well as a nail-biting read. Hedin lived in an age when maps really did have big blank spaces: that magical label, Terra Incognita. Having witnessed as a child the triumphant return of a North Pole explorer, he decided it was his vocation to fill in some of those spaces. And so begins his great story, as he sets off towards the uncharted desert from … Trans-Caspia.

Where, you ask? One of the joys of reading very old travel books is that they force you to look up the way stations on a map, trying to mentally redraw the national borders and match up the place names. I read Hedin’s account with a giant Times Atlas balanced on the sofa arm, and my knowledge of Turkmen-, Uzbek- and Tajikistan is vastly improved as a result. (Admittedly, it started from a low base.)

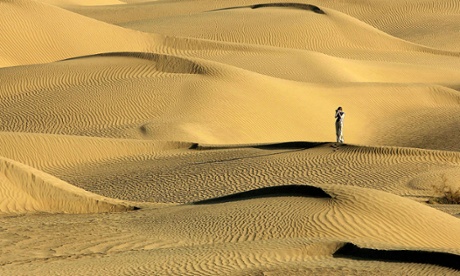

The best bit of My Life As an Explorer – by which, of course, I mean the worst – is Hedin’s horrific journey across the Taklamakan desert, bordering on the Gobi in the northwest of China. Before he set off, a local man, keen to join his group, airily told him he would need only four days’ worth of water to see him safely across to the nearest river. Not so. By day seven, Hedin knew he was in serious trouble. His camels, dogs and Tajik guides began to succumb to the ravages of thirst as the little band inched across the map. Once you’ve read Hedin’s account of what happens to the tongue and throat when a body is deprived of water, you’ll never need to read another.

Later, he trekked across Tibet, where he mapped so many mountains that they named the range after him. (Not for long; it’s now known as the Transhimalaya.) There, he had to contend with not only the cold and aridity of the high plains, but also the hostility of the locals. At that time, Lhasa was closed to westerners; the punishment for trespass was death. That didn’t stop Hedin from trying to get in. He disguised himself as a Tibetan, but almost gave himself away by quaking with fright whenever an official came near.

I discovered Sven Hedin in A Book of Travellers’ Tales, an excellent anthology put together by Eric Newby, the writer and Observer travel editor. Sadly, like this book, it’s out of print. But if you ever find it, tucked away among the Dick Francises on a holiday cottage bookshelf, do look up Sven Hedin – and give him my best.