Alain Mabanckou (Republic of Congo)

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

My novels often feature “grotesque” characters who hail from Congo’s poor, popular, working-class neighbourhoods.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

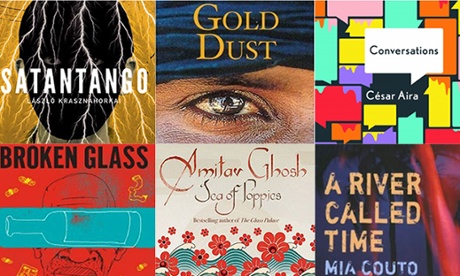

Tomorrow I Will be Twenty is a good introduction to my early years, but readers tell me they find Broken Glass really funny.

As a writer, do you feel that there is a distinction between a home and an international readership?

The Congolese feel as if they help me write my books, whereas foreign readers are transported to the Congo without needing a passport.

Who are your literary heroes?

Robin Hood, Saint-Éxupery’s Little Prince, and Victor Hugo’s Jean Valjean from Les Misérables.

Is it the duty of a novelist to engage with the political issues of the day?

Writers are first and foremost citizens and as such have a responsibility when it comes to political issues.

Tell us something new about yourself.

I’ve been working on the screenplay adaptation of my 2009 novel Black Bazaar … and I decided about a month ago to let my beard grow. I hope to keep it for a long time …

Amitav Ghosh (India)

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

Much of my work is about journeys, along paths not usually taken.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

My forthcoming novel Flood of Fire may well be the best introduction to my work.

As a writer, do you feel that there is a distinction between a home and an international readership?

I think some distinctions exist but are ultimately unimportant; in the end writers create their own readership, which is drawn to them for reasons other than proximity.

Who are your literary heroes?

I think it’s a bad idea to treat writers as heroes; they should be, in the first instance, writers.

Is it the duty of the novelist to engage with the political issues of the day?

No on both counts: “political” and “issues of the day”. Writers should engage with matters of significance, and these are often not issues of the day – climate change is a good example. Nor can climate change be defined as narrowly “political”; like literature it is about much more than that.

Tell us something new about yourself.

I’ve become very interested in growing spices. My homegrown black pepper is exceptionally good, even if I say so myself.

César Aira (Argentina)

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

Once I defined my books as “Dadaist fairy tales”. I don’t know if it is completely correct, but it gives an idea. What is certain is that they are purely literary (“literary toys for connoisseurs” was another description): they don’t have social matter, nor psychological, politic, historic, ecologic matter, nor anything of that sort. They are just ludic forays into the imagination.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

I wouldn’t dare recommend any of my books to anyone. I would be afraid they think that I am recommending myself, and I never do that. I don’t recommend even reading. It should be a free choice.

As a writer, do you feel that there is a distinction between a home and an international readership?

I have noted a clear difference in the critics. Abroad, they contextualise me with tango and gauchos; at home, with Raymond Roussel and surrealists. In the world I am an Argentine writer, in Argentina I am a writer. Readers are usually more generous than critics. But I only know the generous readers, not the other ones.

Who are your literary heroes?

I have the good fortune of not being an iconoclast, so my literary heroes are everybody’s literary heroes: Shakespeare, Dante, Cervantes, Baudelaire, Kafka, Proust, Borges, many more in the top shelf. In a more particular line of predilections, Lautréamont, Marianne Moore, Denton Welch, Gombrowicz. But I should include another set of heroes, no less important for me: Duchamp, Cecil Taylor, Neo Rauch, Godard…

Is it the duty of the novelist to engage with the political issues of the day?

A writer should have no duties, not even the duty of writing well. And least of all unto politics. I have not the least sympathy for these useless and destructive pastimes, football and politics.

Tell us something new about yourself.

I am translating, for pleasure, the Life of Savage, of my longtime master hero, dear Dr Johnson.

Fanny Howe (US)

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

My novels are about a generation of Americans who lived between 1940 and 2000, who resisted the postwar political and cultural forces by choosing a wandering life of impoverishment and wonder. Inevitably, race and economics are a big part of their stories. Childhood, childishness, and children are never far. I grew up reading 19th-century novels and late Victorian children’s books, so I try for a good story full of coincidence and error, landscape and weather. However, the world was radically changed during my lifetime, and I tell of that battering as best I can.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

I would recommend to a reader of fiction Nod, The Deep North and Indivisible. These are all collected in one volume, Radical Love. Two collections of my poems were published in England by Reality Street Press: O’Clock and Emergence. And two collections of essays, The Wedding Dress and The Winter Sun, would give a reader an introduction to my interest in religion and philosophy.

As a writer, do you feel that there is a distinction between a home and an international readership?

I have found that, at home, the survival of unconventional writing is all thanks to small presses who also publish poetry. This fusion has created a hybrid form that is very interesting to me. This change is probably true around the world. Magic realism and the explosion of prose poetry were part of this movement. I was involved in the adaptation of poems from Polish into English by two sisters who wrote them through their youth in Buchenwald, and this way I wrestled with the experience of translation, prison writing, and oppression.

Who are your literary heroes?

My immediate list would include James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston, Julio Cortázar, Garcia Márquez, Marguerite Duras, Samuel Beckett and before them, the Brontë sisters, Rilke, and Thomas Hardy. The delicious chaos in the middle would be James Joyce. In poetry, I have, since very young, loved poetry in translation. The Chinese, the French, the Russians, Italians, Indians and early Celts: the formality of the translator’s voice, their measured breath and anxiety moves me as it lingers over the original.

Tell us something new about yourself

I was a go-go dancer at the Dom on East 10th Street in NYC. This was a glittering ballroom over Stanley’s Bar. 1965.

Hoda Barakat (Lebanon)

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

How to answer this, especially if you don’t know the person, apart from saying: “Read me, and I hope you will like it!” I would add that these books are emotionally difficult to write, and perhaps that they tell the stories of characters who are either marginal, isolated, or innocent, who are subject to violence that transforms them.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

Probably the first, hoping that the reader will then try more!

As a writer, do you feel that there is a distinction between a home and an international readership?

I don’t think so, no. I’ve had the luck to meet readers of different backgrounds, languages and countries, and their comments generally weren’t much different from those of my Arabic-speaking or Arab readers.

Who are your literary heroes?

There are lots of them and they are all different. In each novel or play that I’ve read, or even music that I’ve heard, the characters that I’ve liked have helped shape me and were my heroes, up to the point of considering them to be aspects of reality and not creations of fiction. So that Werther was more real than my younger brother, Macbeth filled my dreams and anxieties more than the beginnings of war in my town … With the advantage of being able to read in two languages, Arabic and French, I had the extraordinary luck of feeling like I belong to a family of people around the world, and also of all times!

Is it the duty of the novelist to engage with the political issues of the day?

I don’t believe that a writer has “duties”: it is enough for a writer to do their job well. However, it’s true to say that a writer is indirectly the witness of their time, even through what they omit from their work, and denial of the “great causes” of their times is bearing witness to it as well.

Tell us something new about yourself.

I’m a grandmother! And very happy to be one! My granddaughter is called Yasmine.

László Krasznahorkai (Hungary)

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

Letters; then from letters, words; then from these words, some short sentences; then more sentences that are longer, and in the main very long sentences, for the duration of 35 years. Beauty in language. Fun in hell.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

If there are readers who haven’t read my books, I couldn’t recommend anything to read to them; instead, I’d advise them to go out, sit down somewhere, perhaps by the side of a brook, with nothing to do, nothing to think about, just remaining in silence like stones. They will eventually meet someone who has already read my books.

As a writer, do you feel that there is a distinction between a home and an international readership?

No, I don’t; readers with empathy are the same all over the word.

Who are your literary heroes?

I have only one: K, in the works of Kafka. I follow him always.

Is it the duty of the novelist to engage with the political issues of the day?

No, under no circumstances. Artists have no duties whatsoever. Just freedom without borders, the answer to which is despair.

Tell us something new about yourself.

I’d prefer to supply some helpful information: the pronunciation of my name in English: [krαsnαhorkα.i]

Marlene van Niekerk (South Africa)

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

Difficult question. I would say a high degree of specificity. Thick description. There is a vain ambition that propels my efforts: to write something that will at least surprise and at best confound me – and hopefully the reader. This involves a certain hellbent relationship with language. I try to “make it” lead me into the unknown by forcing useful “accidents”. Seduction, coercion, treason, egg white, Biblical rhythms, anything to mobilise “the other” of writing. To provoke the resistance of what refuses to be written.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

Agaat releases its effect incrementally. Many people find Triomf a rollercoaster. Some readers might find Memorandum a curious affair, but because of the strange synergy with the hospital paintings of Adriaan van Zyl [which appear alongside the prose], it might be the most rewarding of my attempts so far. I could suggest that the reader tries a poem as appetiser, there are a few from the collection Kaar (2013) that I have tried to translate on the website of Rotterdam Poetry International.

As a writer, do you feel that there is a distinction between a home and an international readership?

Yes, there certainly is. I always have an internal debate, or rather a debacle with South African readers when I write. The majority of my readers are not resident in South Africa but in the Netherlands and in Sweden. So no, I do not intentionally direct myself to an international readership, I would not know how to do that, I am a country girl. It could however be precisely the undertow of this local debate, or the positions in the debate that capture the international reader. There is always a judge, a blackmailer, a complainant, a confessor, an accomplice, a collaborator, a rescuer, a resister, an accuser, an accused, a refugee, a prisoner, a warden, a witness, a victim, a prey, a parasite, a predator, a torturer, a mute, a translator, in these debates. This obsession with power struggles causes a torque in the writing; a constriction of the breath that I think sometimes captures a certain kind of kinky foreign reader even if the setting is local.

Who are your literary heroes?

I have been reading more non-fiction than novels lately: “big history” (the history of energy, beginning at the Big Bang up to the destructive fuel extraction of global capitalism), political theory, economic history, ethology, anthropology, and especially a certain type of philosophy. I sometimes find a stylistically gifted speculative philosopher like Peter Sloterdijk or Michel Serres or Jean-Luc Nancy or Deleuze and Guattari more engaging to read than literary prose: passionate, entertaining, provocative, imaginative, argumentative and pretty meaty. What novelist can write like that? JM Coetzee does. Prose that thinks. But stripped entirely of the philosopher’s wordiness and swank.

Is it the duty of the novelist to engage with the political issues of the day?

It is a political act to write, tout court, and one is caught up in the stories of one’s time whether one likes it or not. The obvious point is that one assumes power when one writes and the trouble starts when one (as a white writer in South Africa) realises this and then is old-fashioned enough to try and get a grip on the “accountabilities of form” involved in an act that assumes such authority. That is, if one is narcissistic or foolhardy enough, on top of it all, to want to “out” your damned act, ie publish it. One can also put it in a drawer or in a will and escape the contestations.

Tell us something new about yourself?

I talk to owls. I go out at night when I hear them calling and join in. Sometimes when the weather is “owly”: sweet, clear and resonant, I just start hooting in the dark until one answers. They get in quite close sometimes to check who is interfering in their territory. They probably think I am amakwerekwere* but so far they seem to engage with alacrity. It is the game of my heart, it strangely consoles and relieves me. The fellowship of breath. It was a thrill when I then happened upon Seamus Heaney’s analysis in Finders Keepers of Wordsworth’s owl-poem, There Was a Boy.

*amakwerekwere is the name that xenophobes give to foreigners in South Africa referring to their speech.

Mia Couto (Mozambique)

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

I use dreams and words and feelings to produce stories. My writing is my passion and I don’t consider it as “work”.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

From my novels I would choose The Sleepwalking Land. From my short stories, Every Man Is a Race.

As a writer, do you feel that there is a distinction between a home and an international readership?

Yes. What can be read and understood as “surreal” by an outsider will be perceived as “natural” by a reader from Mozambique.

Who are your literary heroes?

Fernando Pessoa (Portugal) and Guimarães Rosa (Brazil).

Is it the duty of the novelist to engage with the political issues of the day?

Not a duty. But something that can’t be avoided. Otherwise politics will engage with the novelist.

Tell us something new about yourself.

My books are the only part of me that is interesting.

Maryse Condé (Guadeloupe)

How would you describe your work to someone who is unfamiliar with it?

I was born on the tiny island of Guadeloupe, which never makes headlines unless there is a hurricane or an earthquake. All my work attempts to prove that such an approach is simplistic. Guadeloupe, where African slaves, Indian indentured labourers and the European colonisers met, has a complex and fascinating culture to decipher.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

I would recommend my books with an autobiographical theme and a Guadeloupean perspective: Tales from the Heart: True Stories from My Childhood; Victoire: My Mother’s Mother; I Had a Dream of Africa (the provisional title for a forthcoming translation); and my last book Mets et Merveilles (“Marvellous Meals”, not yet translated into English).

As a writer do you feel there is a distinction between a home and international readership?

There is certainly one distinction: people at home are more familiar with the realities that you describe. But this is not necessarily a positive element. An international readership dreams more freely about unfamiliar topics.. Nothing is more satisfying than discussing my work with a Japanese audience, for example, so far and so different from my people at home.

Who are your literary heroes?

Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights; Tess of the D’Urbervilles; James Ramsay in To the Lighthouse; Marguerite Duras in The Lover.

Is it the duty of the novelist to engage in the political issues of the day?

No, I don’t think so.

Tell us something new about yourself?

In my last book Mets et Merveilles, I reveal a little-known facet of myself. In my life I have two passions: writing and cooking. I explain how for me both activities derive from the same desire to create, either with words and images or with food.

Ibrahim al-Koni (Libya)

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

To answer this question I would need to write all my works again. If forced to reply, however, I would say that I will shock readers who seek entertainment in literature and not truth, because the literary search for truth is a wail that always arises from pain. For writers like me literature is a mission, and having a calling like this implies an acceptance of the cross and the blood that washes the cross; this is true for every prophetic mission in the world. Therefore I am unable to offer a formulaic definition, because if the devil is in the details, as we say, truth also dwells in the details.

Which of your books would you recommend to a reader approaching your work for the first time?

All my books are my progeny. There is no superiority for one over the others. But if I am forced to name one book that provides a key to my works in English, it would be al-Tibr (Gold Dust). My major work, the epic al-Majus, has been available for a considerable number of years in German and French translations but still has not yet appeared in English.

As a writer, do you feel that there is a distinction between a home and an international readership?

Perhaps the distinction between the foreign and Arab reception of my works is that the recognition I receive from the Arab reader, in whose language I write, is based almost entirely on the international recognition my works have received. What I call “the mission or message text” normally does not find a brisk market easily. The quest for God is a perilous adventure and encountering reality is not a blissful endeavour!

Who are your literary heroes?

All the emblematic figures in world literature have been heroes for my literary journey, beginning with the epics of ancient literature and ending with 20th-century literature. These include the Old Testament, especially Genesis and Ecclesiastes, the works of Saint Paul and Saint Augustine, and the texts of ancient India like the Rig Veda and the Upanishads, the Dao De Jing, Greek, Roman, and Classical Arabic literatures, Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes, [and on to] Dostoevsky, Balzac, Faulkner, Mann, Kafka, Galsworthy, and the others.

Is it the duty of the novelist to engage with the political issues of the day?

I have always been suspicious of politics, for many reasons. The most important of these is its intimate relationship with truth’s number one enemy: ideology! A novelist infected by the curse of politics inevitably falls prey to it. Then he sentences himself to death as far as creativity is concerned. This naturally is not a call for living in an ivory tower, as the saying goes. It does, however, mean adopting extreme caution when writing a political narrative – especially in a world that is accustomed to reducing existence as a whole to politics. To cite an eminently existential subject like freedom, for example – a purely political end will kill the spirit of truth in it, unless it arms itself with a life preserver: in other words, with myth.

Tell us something new about yourself.

If I were to say something new, it would be that a new thought cannot be articulated, because we never say what we want to say … Indeed, we do not add anything new to what has been said before us, except the degree of its relationship to the eternal question of the creation, the metaphysical identity that inhabits us. The extent of our success or failure in articulating this is the criterion that will raise or reduce us!