Kamila Shamsie calling for a year of publishing only women has certainly unleashed a storm. Some disagree that gender bias exists, while others would rather celebrate the commercial success of some female authors. A couple of publishers have even taken Shamsie at her word.

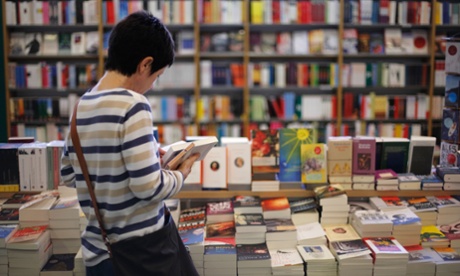

Most people agree that this is a complex issue, with so many levels during the publishing process at which bias can be perpetuated that it is impossible to pinpoint why and how many female writers struggle for recognition against their male counterparts. But one vitally important aspect of this debate seems to have been overlooked: books, once published, must be sold, and while many transactions are conducted online, many others continue to occur in old-fashioned brick-and-mortar shops. Customers don’t just buy what they’ve read about, they come in to browse, to find out what’s available, or to see what their local booksellers have enjoyed.

Sophia McDougall raised this point last year when she wrote in the New Statesman about how she started counting the number of male and female authors promoted by bookshops on display tables. There are numerous ways gender bias manifests itself in a bookshop, from the decisions about which books to stock to the decisions about which to discount and which to feature as a staff pick. Then there’s choosing which books to display, promote or put on overstock tables. (This always comes down to stock levels, which reflect expected sales: if bookshops have more bulk quantities of male authors because that is what is expected to sell, it’s worth investigating why).

As if this isn’t complicated enough, there’s the issue of genre. Not all genres (paranormal romance, for example) are biased against female writers. And we need to stop talking about books as if they are all the same thing, subject to the same publishing and marketing decisions. Then there’s the issue of subject area – not unlike some recent mutterings about women in science – where the availability of titles may make gender parity in a section simply impossible. And we must also consider the English-language canon: the dead, straight, white European men whose work has been so privileged for so long that they have remained in print, when many women have not – thereby claiming a greater proportion of the bookshelf.

But never underestimate the importance of consciousness raising. Since reading McDougall’s article, I have changed the way I approach my job, as have several of my colleagues at Foyles. I am reading more books in translation, more books by writers from different racial or cultural backgrounds to my own and vastly more books by women. As a result I have included more books in these categories as my staff picks, not to achieve quotas, but because they are bloody good books. I consider gender when deciding which new titles to stock in my section, and which books to feature and promote. Our database of staff picks now contains a column noting the author’s gender, so we can track whose work is being showcased, and where (in the front of house, where everyone can see, or in an area with less foot traffic?). I’m not saying we’ve achieved parity by any means – and sales will continue to be influenced by external factors – but we are certainly more aware, more alert to existing bias, and more committed to changing it.

As McDougall wrote: “I don’t think there’s any grand, mustachio-twirling conspiracy to keep women down. But there doesn’t have to be. If you pick books from what you see around you and what you’ve grown up with, and the names you see in the trade press, none of which requires any sort of malice, the monoculture persists.” If bookshops and booksellers promote diversity – not only of gender, but also of race, culture and sexuality – wherever possible, perhaps we will begin to see the changes Shamsie and so many others are hoping for.