You could be forgiven for seeing Everyman, an early-Tudor morality play in which the titular hero is summoned by Death to judgment, as a cultural cul de sac. In fact, it has a remarkably rich legacy, stretching across more than 500 years to Carol Ann Duffy’s reworking that has recently opened at the National Theatre.

John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678)

Drama becomes allegorical fiction, and Everyman becomes Christian en route to the Celestial City, but Bunyan’s ampler version of the search for salvation is also tale of fruitful or frustrating encounters with characters personifying virtues, vices or temptations. Its influence was enormous in the 19th century, stretching from Charlotte Brontë, Dickens, Thackeray and Melville to Shaw – so arguably indirectly Everyman’s was, too, although the play itself went unperformed until 1901.

Everyman’s library (launched 1906)

Five years after the first modern revival (a landmark production that toured internationally), JM Dent began his series of classic books, each with an epigraph from the play. This was also in effect the launch of Everyman the brand, with the name later given to cinemas, theatres, comic book characters, etc. Only in the 70s (when the gynaecological guide Everywoman appeared) did it start to drop out of favour as feminism gained ground.

Hugo von Hoffmannsthal, Jedermann (1911)

Best-known as Richard Strauss’s librettist, the Austrian playwright took time out to pen this German adaptation of Everyman, which since 1920 has been staged annually al fresco at the Salzburg festival, with the cathedral as backdrop. Billed as “the tale of a rich man dying”, it is now performed in smart costumes mirroring festival-goers’ evening dress.

Franz Kafka, The Trial (begun 1914, published posthumously 1925)

As it’s known that Kafka admired Von Hoffmannsthal and saw Jedermann, it isn’t a big stretch to discern its influence on his novel and its Everyman-like hero K. The Trial, on this reading, strips the play of its Christian elements and allegorical figures but still follows an anxious journey towards judgment – now a secular trial with multiple symbolic associations, rather than a reckoning before God.

Ingmar Bergman, The Seventh Seal (1957)

Bergman directed a radio production of Jedermann a few months before writing the screenplay of this film set in medieval Sweden, in which a knight is challenged to a game of chess by a personification of Death.

The Prisoner (TV series, 1967-68)

The hero (“I am not a number, I am a free man!”) held captive in a sinister village and labelled No 6 faces potential extinction of identity rather than death, and his dealings with friends and enemies are inflected by thriller elements and 60s surrealism, but the debt to the medieval play’s set-up and generic protagonist is signalled in the name of its star and co-creator Patrick McGoohan’s production company, Everyman Films.

Woody Allen, Love and Death (1975)

Contains a parody of The Seventh Seal, including the chess game and the concluding dance of death. Later uses of the same tropes (eg in Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life and Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey) can’t count on viewers knowing their Bergman, let alone their medieval morality drama.

Philip Roth, Everyman (2006)

A number of postwar US writers (eg Arthur Miller in Death of a Salesman) have deployed “everyman figures”, but Roth unusually made the Tudor connection explicit in this pared-back late novel in which the hero knows he is dying and reviews his life.

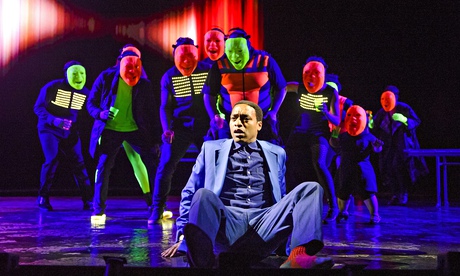

Carol Ann Duffy, Everyman (2015)

Chiwetel Ejiofor’s shallow rich man can no longer count on friends, family and possessions when confronted by Death in the poet laureate’s contemporary version, and his sins now include the 21st-century vice of trashing the environment.