JD Salinger’s Holden Caulfield is to the 20th century what Huckleberry Finn is to the 19th: the unforgettably haunting voice of the adolescent at odds with a troubling world. Holden, the opposite of Huck, is an unhappy rich boy who has done a bunk from his posh secondary school, Pencey Prep, in Agerstown, Pennsylvania. He begins his first-person narrative in words that echo the famous opening of Twain’s novel (No 23 in this series), a frank disavowal of “all that David Copperfield kind of crap”.

Holden declares that he isn’t going to tell us “about this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas just before I got pretty run-down”. Actually, that’s just what he does, writing (apparently in retrospect from California) about three days in December 1949 when, having been chastised by his school “for not applying myself”, he plays truant over a long and memorable weekend in Manhattan. Holden is tortured by the battle to come to terms with himself, with his little sister Phoebe, and their dead brother Allie. Like many adolescents, he feels that the world is an alien, hostile and comfortless place run by “phonies”.

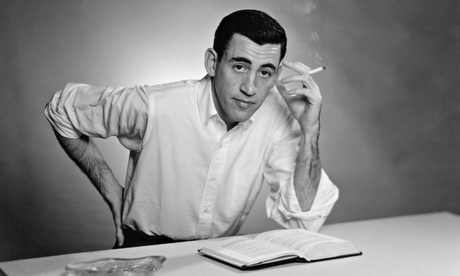

One of the many remarkable things about Salinger’s portrayal of Holden Caulfield is that he seems to be fully inside the head of this troubled 16-year-old when the author himself was almost twice that age. Salinger had fought in Europe as an infantryman, after landing at Utah Beach on D-day, and later saw action at the Battle of the Bulge. Quite a lot of the downtown action in The Catcher in the Rye (a night out in a fancy hotel; a date with an old girlfriend; an encounter with a prostitute, and a mugging by her pimp) might almost as well describe a young soldier’s nightmare experience of R&R.

That’s just one reading. Salinger’s masterpiece (he published comparatively little after its appearance) has also influenced later writers with angry protagonists, from Martin Amis’s Charles Highway to Philip Roth’s Portnoy and many others besides. The Catcher in the Rye remains the crazy, and often very funny, distorting mirror in which generations of British and American teenagers will examine themselves. At the same time, it instructs them to give nothing away to “the phonies” who ruin all our lives. “Don’t ever tell anybody anything,” says Holden Caulfield, echoing Huck Finn again. “If you do, you start missing everybody.”

A note on the text (and its afterlife)

The Catcher in the Rye had some difficulty finding a publisher. One editor judged its protagonist simply “crazy”. The New Yorker, which had favoured Salinger’s stories, stalled with indecision. Eventually, it was published on 16 July 1951, by Little, Brown in Boston, with a famous, award-winning cover designed by E Michael Mitchell.

Salinger had been working towards his masterpiece, in sketches and drafts, for a decade and more. Some of his earliest short stories, written as a student, contain characters reminiscent of those in The Catcher in the Rye. Indeed, while still at Columbia, Salinger wrote a story, The Young Folks, that included a character described as a prototype of Sally Hayes (Holden’s old flame). In November 1941, Salinger also sold a story (Slight Rebellion Off Madison), featuring a disaffected teenager with “prewar jitters” named Holden Caulfield, to the New Yorker. After the outbreak of war, in which Salinger served as an infantryman, the piece was considered unpatriotic and did not get published until December 1946. Meanwhile, another story entitled I’m Crazy, containing material that was later used in The Catcher in the Rye, appeared in Collier’s magazine on 22 December 1945. Another long story about Holden Caulfield was accepted by the New Yorker for publication, although it never appeared.

The Catcher in the Rye continues to hold its place as the defining novel of teenage angst and alienation. My friend, the critic Adam Gopnik, says it is one of the “three perfect books” in American literature (the others are The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby, Nos 23 and 51 in this series). Gopnik says that “no book has ever captured a city better than The Catcher in the Rye captured New York in the 50s”. Book and author quickly acquired a mystique, partly abetted by Salinger, who cultivated his obscurity to the point of mania, becoming as secretive and self-obsessed as Holden Caulfield, in the words of the New York Times, “the Garbo of letters”. Apart from this novel, Salinger published just one collection of stories and two short books about the Glass family (see below), which some readers prefer.

However, between 1961 and 1982, The Catcher in the Rye became more studied in the high schools and libraries of the United States than any other novel. By 1981, it was the second most taught book in the United States. Teenagers especially loved the book for what is taken as Holden Caulfield’s sponsorship of rebellion, combined with his promotion of drinking, smoking and sex. More seriously, there is the grimmer association of The Catcher in the Rye with the murder of John Lennon by Mark Chapman, and John Hinckley’s failed assassination of Ronald Reagan.

Salinger himself remained sequestered from the world in New Hampshire. “There is a marvellous peace in not publishing,” he said, some 20 years after he first fell silent.

Three more from JD Salinger

Nine Stories (1953); Franny and Zooey (1961); Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction (1963).

The Catcher in the Rye is published by Penguin (£8.99). Click here to order it for £7.19