Peter Lennon, who has died of cancer at the age of 81, was at the same time a Dubliner, an honorary Parisian and a Guardian man. The honesty and integrity of his writing during two lengthy periods on the newspaper were also reflected in his one excursion into film, Rocky Road to Dublin (1968), which was both an indictment of and an impassioned plea for his native Ireland, and quickly came to be recognised as a documentary masterpiece. "If one is a true patriot, you criticise your own country," he later wrote when reflecting on the uproar it caused.

His relationship with the Guardian was not always smooth. During budget cuts in 1969, the paper, which had been struggling financially, suddenly let his contract lapse after a decade of distinguished freelance service in Paris. He successfully sued, arguing that the paper had been indefensibly stingy with his severance pay – only to return a decade after reaching a settlement in 1973 to spend practically the rest of his life writing for it. His claim had been backed by a legal threat to have the "international" edition (copies sent to France) impounded by the authorities.

After his departure from the Guardian, he wrote first for the Sunday Times during the editorship of Harold Evans, to whom he was introduced by Michael Frayn, and then for the Listener, published by the BBC. His main contribution to the Sunday Times was a long stint as television critic, an unusually influential one in his insistence that the medium should develop a strong visual language and character of its own.

Typically, when the printers of the Times and Sunday Times were locked out in November 1978, taking both titles off the streets for a year, it was Lennon – he abhorred a vacuum – who broke the silence. He edited a substitute newspaper, the Sunday Times Reporter, with Lew Chester. Productive though Lennon was at the Sunday Times, Chester and other colleagues say that he continued to regard the paper that had cast him out as his natural home.

Lennon left the Sunday Times only when Rupert Murdoch loomed, not waiting long enough to become a Wapping refusenik when the operation moved to the East End of London in 1986. By then Lennon had gone to the Listener, whose editor, Russell Twisk, became a lasting friend.

The radiant eloquence and wit of his best writing in the end ensured his reconciliation with the Guardian. His byline had reappeared in the mid-1980s on the book pages, edited by WL Webb. He was formally rehired on a contract in 1989 by the present editor, Alan Rusbridger, at that time the features editor, who knew nothing of the earlier dispute. Lennon wrote features for the Guardian and pieces for the website until his "retirement" in 2005, when colleagues were surprised to discover he was 75. He continued to write occasionally, his last piece appearing in May 2009.

Lennon had fled from Ireland, although only tentatively at first – his ticket to Paris was a precautionary return – in his mid-20s. He had been born into a family once of moderate prosperity whose fortunes had been dissipated in drink, which was readily to hand – they had been wine merchants. His father was a freelance salesman, but it was Lennon's mother, who lived until she was 99, who kept the family together.

Lennon survived, he would say, not so much frugality as an education by the Christian Brothers – scenes in Rocky Road to Dublin were filmed in the actual classroom he had occupied. He left school not for university, but work. It was from the imprisonment of a job in a Dublin bank (once a mortuary) that he escaped to Paris, although he had already sensed a route to freedom in the pieces he had started getting published in the Irish press.

Once in France, he fitted into the interstices of Parisian life. He lived precariously by giving English lessons and filing reports for Irish newspapers – factual insofar as his stumbling progress in French enabled him to tell: they were mostly culled from French newspapers.

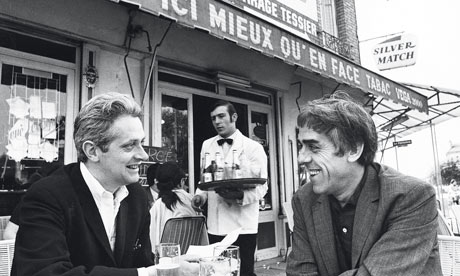

He formed a lasting friendship with his compatriot Samuel Beckett, one that survived the award of Beckett's Nobel prize in 1969 and all the pressures that went with it, although meetings became more sparse. Before that, they often met and shared what Beckett called "a jar". His handwritten letters and notes to Lennon, spanning about 15 years from the beginning of the 1960s, shelter in the Guardian archive – the content screened by a tiny and almost indecipherable script.

Lennon's own considerable literary potential was never fully realised. He wrote promising short stories for the New Yorker (which on at least one occasion brought congratulations by Beckett) and the Atlantic Monthly, which led to book offers and advances, but the novel never materialised. He had an impatient talent, and quite often an urgent need to eat.

His relationship with the Guardian began when he submitted his first piece, as he was turning 30. He provided the paper with rich coverage of French cultural life throughout the 1960s. One of his slightest offerings also became one of his best known – a piece about the fin de siècle phenomenon Joseph Pujol. As Le Pétomane, Pujol had packed theatres with performances in which he exercised an unusual ability to inhale through the rectum and exhale musically. "Not to beat about the bush," Lennon wrote, "he could fart like nobody else in the world, before, then, or since."

He had an excellent relationship with the Manchester features office, particularly Brian Redhead, who imposed only one restriction: he was asked not to encroach on the territory of the paper's regular Paris correspondent, Darsie Gillie. But the war in Algeria was seeping into the streets and environs of Paris, and in October 1961 a demonstration had been suppressed by the police, who were accused of lynching some of the demonstrators.

In his lively biographical account of these years, Foreign Correspondent, Paris in the Sixties (1994), Lennon recalled: "I wrote a theatre piece into which, in recounting the reasons for missing the performance, I packed many of the details of the October slaughter." It was run without question as a page lead under the heading of his regular column, La Vie Parisienne, with the additional headline, Strange Fruit in the Woods. The strange fruit were the hanging bodies of the lynched protesters. "I never mentioned the piece to Darsie and he never reproached me. From that moment I felt complete- ly at ease with the Guardian."

For Lennon, Paris put Dublin and Ireland in perspective. He was dispatch- ed by the Guardian to cover the Dublin book festival. This, along with bar-room reunions with friends who insisted that Ireland was changing in ways he could not detect, goaded him into writing a series of articles on the condition of his native land. These criticised the climate of repression, the censorship, the claustrophobic narrowness of the classroom, the provincialism of sporting life, but particularly the grip of the clergy. They provoked a furore that aroused in him not dismay, but confirmation and indignation.

This experience led him to make the feature-length Rocky Road to Dublin. He found a friend in Paris to put up the money. His younger brother Anthony became one of the producers. Most remarkably, he succeeded in enlisting the services of Raoul Coutard, the cinematographer who had worked for Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and other directors of the nouvelle vague. Lennon's only experience of film-making at that point had been an abortive spell as an extra and writer of English dialogue (never used) for Jacques Tati, who was working on Playtime.

The film reflected the theme of the articles and caused even greater uproar when a glimpse of it was shown at the Cork film festival in 1967, before a longer commercial showing in Dublin. It was in itself something rare, a full-length film on Ireland made by an Irishman. One of its interviewees, John Huston, who happened to be filming in the Wicklow mountains, advocated this as an antidote to the Ireland of Hollywood which he himself represented.

Lennon wanted his film to be a personal essay, with the camera used as the writer used a pen. As he put it in the commentary that he wrote and spoke himself in his beautiful tones, it was an attempt "to reconstruct the plight of an island community which survived more than 700 years of an English occupation and then nearly sank under the weight of its own heroes and clergy ... The question now was: what do you do with your revolution once you've got it?"

His thesis was that the hopes of the revolutionary generation of 1916 and later had been betrayed by something like a conspiracy between politicians and the clergy. There are many memorable sequences: the boys in his old classroom standing to recite "Because of Adam's sin ... our intellect is darkened and our will is weakened" and speaking of "the abomination of bad plays, films, books, pictures – and miniskirts"; the editor of the Irish Times talking about wrestling with the controversy surrounding "the pill"; a hurling match, an approved Irish sport – there was still a ban on "foreign games", soccer, rugby, cricket and hockey, in 1967; a wonderful singing sequence in a bar, where the song from which the film takes its title, Rocky Road to Dublin, is in the repertoire; and, most telling, the not unkind but at the same time agonising record of two days spent with a priest nominated by the archbishop's office: "We are not against sex ... I personally would like to be married."

In fact, as Lennon later discovered, the priest was in an illicit relationship with one of his parishioners.

To the consternation of the Irish authorities, the film was chosen for critics' week at the Cannes film festival in 1968 – the last film shown before the festival was stopped as a gesture of solidarity with the protesting students and workers. After almost three decades of virtual exclusion in Ireland (it was never officially banned), it was restored by the Irish Film Board and screened with Paul Duane's The Making of Rocky Road, in which Lennon was also closely involved, at the Cork film festival in 2004.

That was a kind of homecoming for Lennon. "People might now begin to see it as a very affectionate film about Ireland," he wrote. "Because it attacked the institutions, they missed the point that it was on the side of the people."

Not long after the start of his Paris period, he met and in 1962 married a Finnish student, Eeva Karikoski – she always insisted she had picked Peter up – who also became a journalist. As Eeva Lennon, she continues to report from London for the Finnish Broadcasting Company. They had two children, Samuel and Suzanne, both born in Paris. All three survive him.

• Peter Gerard Lennon, journalist, born 28 February 1930; died 18 March 2011