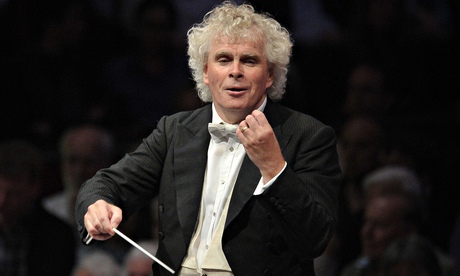

Simon Rattle has been “Britain’s leading young conductor” for so long now that it is a shock to realise that he turned 60 this month. The famous frizzy hair is greying, the shoot-from-the-hip witticisms are (sometimes) modified by political prudence, and observers would say that his interpretations have deepened and broadened over the years without losing any of the visceral excitement that first established him as a musical dynamo. He has potentially plenty more decades in view: conductors tend to live as long as Titian, possibly because of their combination of regular physical exertion and extensive creature comforts: Pierre Monteux famously requested a 25-year contract from the London Symphony Orchestra when he was 86.

But it has been quite possible for British audiences to overlook Rattle in the past decade and more, because he has been out of the country at the helm of one of the world’s great orchestras, the Berlin Philharmonic, since 2002. He has made occasional visits to London with the Berlin players, appearing here regularly only with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, the period-instrument band which he introduced to Glyndebourne and continues to conduct, and making returns to his native Liverpool during its year as City of Culture.

Now all that is changing: Rattle was seen around the world in July 2012 as a conductor in the opening ceremony of the London Olympics. (He was the only one who actually conducted: Daniel Barenboim, after performing at the Proms that night, turned up to carry a flag.) Following the LSO’s Olympics performance – famously subverted by Rowan Atkinson as Mr Bean – Rattle’s relationship with the orchestra has continued to flourish. They had just completed a partnership with Wynton Marsalis at the Lincoln Center in New York; Rattle has since been a regular feature of the LSO’s diary. Earlier this month he gave two high-impact programmes with them in London and Luxembourg, and they share a programme of work in the future. He is to step down as chief conductor of the Berlin Phil in 2018, signing off with a typically sharp reference to Liverpool: “will you still need me when I’m 64?”.

So the last period of Rattle’s Berlin partnership will take on a heightened importance and will be closely watched: what legacy will he leave there? The two BBC Proms he gave with the Berliners last summer could not have been more different: Stravinsky’s Firebird in one, drawing on the unique textures of the Berlin Philharmonic, developed over decades to produce sounds of unbelievable sophistication; Bach’s St Matthew Passion in the other, reimagining that ritual masterpiece in a staging by Peter Sellars that took them out of their comfort zone and challenged the orchestra’s tradition.

The concerts in the ensemble’s London residency in February contain signature Rattle works that are equally contrasted. Mahler’s Second Symphony at Southbank Centre is the piece with which he both started and finished his time conducting the CBSO in Birmingham; it is core Berlin repertory. Not so the Sibelius symphony cycle which he conducts at the Barbican –though Herbert von Karajan recorded almost all those seven symphonies, they have never been accepted in Germany as being central to the European symphonic tradition. Yet, as Tom Service relates in his book Music as Alchemy, Rattle has been totally committed to them: he conducted and recorded the whole cycle early on in Birmingham, and among many others created a lifelong fan in David Yelland, who became editor of the Sun and gave Rattle an unexpected editorial cheer when he was elected to Berlin.

I first met Rattle in his late teens, with his supportive parents at the international Dartington Summer School of Music in Devon, where he conducted with galvanising energy and made friends quickly and easily, while I pushed pianos around and put up music stands. When I began to follow his music-making during his years in Birmingham in the 1980s, and first wrote about him, it was clear that his was an electrifying talent, but no one could tell whether it would burn itself out, develop or simply lose its edge. Rattle, who has a pretty high degree of self-awareness, saw the problem very clearly: “My greatest danger is that I could become too lazy. It could all be too easy.” It wasn’t: he saw to that, and he has continued to build himself new mountains to climb.

There have been innovations, such as the first Wagner opera on period instruments, or a set of new commissions to partner the movements of Holst’s Planets Suite; there have been major strategic decisions, such as removing the Berlin Philharmonic from the warm embrace of the Salzburg Easter festival and creating a new festival in Baden-Baden; and there have been passionate commitments, such as creating an inclusive education and outreach programme previously undreamed of in Berlin. These, and continually driving an ever-widening repertory with the orchestra, have kept Rattle alert, active and often challenged by the powerful individual musical personalities of the Berlin players.

It was no doubt a judgment that irritated others in the musical world, but it seemed reasonable when I defined Rattle a decade ago as “more than just another great conductor … the characteristic conductor of the 21st century”. Consider the sheer breadth of his musical and stylistic sympathies: he explores the French baroque opera of Rameau as readily as the musicals of Bernstein; he brought not only Kurtág but also Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius to the Vienna Philharmonic; he is as much at home with Puccini’s Manon Lescaut in Baden-Baden as he is with Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites at Covent Garden. He has espoused not only Sibelius, but Szymanowski, Schoenberg and Saariaho. His repertoire – from Bach to Boulez, with Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner in between, on modern and period instruments – is way beyond the normal reach for today’s conductors, and represents a stratospherically high level of achievement.

Rattle’s path has been built on clear-sighted planning and his ability not to be deflected from the task in hand. The network of school music lessons, and free provision of local services such as youth orchestras helped his early progress: he first assembled musicians for an orchestral concert in Liverpool when he was 15. Nothing annoyed him more during his Birmingham years, beginning in 1980, than being asked when he was going to move on, and 18 years later he was still at the helm of the orchestra he had built into an ensemble that was in demand around the world (his first cycle of Beethoven symphonies, performed around Europe during CBSO tours, has just surfaced for the first time on Radio 3). He became skilful at declining the most attractive and lucrative offers that did not fit with his chosen path: he could have gone to Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Boston … but what would he have built?

At the CBSO, he built a repertory with his orchestra, developing their skills together and growing gradually into the music, in a tradition more closely related to the longtime music directors of the past, such as Stokowski or Barbirolli, than to the international jet-setters of today. But unlike the maestros of the past, who built their work around the central European classics, Rattle, as a child of the late 20th century, found his centre of musical gravity in Janácek, Bartók, Stravinsky and Mahler, only slowly reaching back to the 19th century classics and beyond.

So what next? The conditions need to exist to enable him to make the greatest music. But it is no secret that he would be welcomed back to London – or rather welcomed to London for the first time. Although he has often appeared here, he has never had a permanent appointment in the capital. If properly supported, this could herald a step-change in our musical life; he could bring changes to our orchestras through his artistic leadership, and at a time when access is top of the agenda, could drive the democratic engagement of the UK with the arts. Rattle would make a powerful spokesman, and a convincing advocate for creative education and young people’s learning, which he has argued for consistently over the years and which he will demonstrate during the upcoming residency through the Young Orchestra for London project where he will conduct an ensemble involving 100 young people from every London borough.

Does he want the challenge, at a time when he could easily step back from Berlin and accept enticing guest conducting engagements around the orchestras and opera houses of the world? If he feels that enough new can be achieved, that musical life can move forward, and that everything he does can benefit the whole of the UK and not only the concertgoers of London, then there is a challenge and a cause for him to take up.

This year’s London residency of the Berlin Philharmonic in February will allow audiences to judge the deepening maturity of his music-making, now that at 60, his experience and ambition are evenly balanced. Looking to the future, one of the last things Rattle’s mother said to me before she died, when he made one of his rare returns to Britain and received the acclaim of a packed hall, was short, sharp and to the point: “He should be here.” Perhaps soon he will be.

- Nicholas Kenyon is managing director of the Barbican Centre, and author of Simon Rattle: from Birmingham to Berlin (Faber). Rattle conducts the BPO at the Barbican, London EC2Y (barbican.org.uk), and Southbank Centre, London SE1 (southbankcentre.co.uk), on 10-15 February.

- The subheading on this article was amended on 4 February to be consistent with the body of the article.