The author Mark Haddon remembers Charles and Camilla's wedding day with fondness - but only because the televised royal nuptials had slipped his mind till he turned up at Cotswold wildlife park with his two small boys, to find the car park empty and "an uninterrupted view of the penguins. We were very thankful."

Haddon is a self-professed republican. Like fellow writer Caryl Phillips, he feels there is no place for the monarchy in 21st-century Britain. The two British authors were bemused to find their principles put to the test after they were awarded the only literary prize in which the Queen takes an active interest.

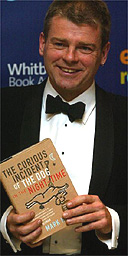

Each year the winner of the Commonwealth Writers Prize for best book is invited for an audience, usually the following spring, with the head of the Commonwealth: the Queen. Yet after Phillips won last year for his seventh novel, A Distant Shore, he quietly and persistently refused the invitation. Haddon, winner of best debut for what was his first novel for adults, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, was in effect asked to take his place, but also discreetly declined. No date, then, for the Queen's diary. As one of the judges, I was intrigued by their stand.

The two writers, who have never met (Haddon hates flying and did not go to Melbourne, where the awards were being announced), say they accepted their prizes before any mention of a visit to Buckingham Palace. According to Mark Collins, director of the sponsoring Commonwealth Foundation, meeting the Queen is "not a necessary or integral part" of the prize, which started in 1987, and whose host city rotates around the Commonwealth. Writers, among them JM Coetzee, Peter Carey, Vikram Seth, Nadine Gordimer, Margaret Atwood and VS Naipaul, value it highly as an ambitious forerunner of the global Impac and Man Booker International literary awards. As Louis de Bernières, who won in 1995 for Captain Corelli's Mandolin, put it, "because the judges come from all over the world, you know you've produced something special".

Phillips and Haddon are agreed on the need for a public debate about the monarchy. For Phillips, who grew up in Leeds and now lives in New York and London, the royal family "represents a particular type of Englishness - not even Britishness - that's comforting to some people, even though they know it bears no relation to reality". That tradition, he says, "sits squarely in a fake conception of Britain ... in direct opposition to what I've been trying to write about for more than 25 years".

A Distant Shore, tracing an encounter between a retired Midlands schoolteacher and a traumatised African asylum seeker, reveals the anxieties of a Britain that bolsters its identity partly by excluding others. "I'm trying to interrogate British history and mythologies and duplicities, and one of the enduring myths is the royal family, which is white and Christian and 'pure-blooded', and on which the sun never sets," Phillips says. Alluding to the royals' German and Greek ancestry, he adds, "there's no evidence of their publicly acknowledging even their own mongrel nature. They're immigrants, but some immigrants are allowed to assimilate with greater rapidity than others because they're white and Christian, and by being very careful about whom they marry. They can't marry a Catholic or Muslim or a Jewish person without some kerfuffle at the highest level."

The 1701 Act of Settlement not only forbids the monarch or heirs to marry a Catholic (or "Papist"), but obliges them to uphold the Protestant line of succession. Renewed moves in parliament to reform the act failed again this year. Yet for Phillips, "it isn't just about amending an act. It's a deep conservatism; a rigid, orthodox sense of what constitutes Britain. People cling to that for safety against immigrants, Gypsies or asylum seekers. If a possible future king thinks that it's OK to dress as a Nazi at a 'Natives and Colonials' party, you erase that, because it's nothing to do with politics, it's just a safe, comfortable image of Britain."

The royal family, in his view, helps perpetuate the "mythology of European 'purity of blood' that buried millions of people in the 20th century". Europe, he says, "became multiracial as a result of a long history of overseas adventuring, and fusion - from Disraeli to Equiano. But you can never look at the royal family and see true British history, because it's hidden, and they're complicit in that."

The ostracism of outsiders is also a theme of Haddon's fiction. The author says his novel, whose sleuth Christopher Boone is an autistic teenager with Asperger's syndrome, shows us that "no one is a stranger. The people we turn away from in the street are more like us than we dare to admit. Christopher happens to have a few behavioural problems, but the world dismisses him as it dismisses people who sleep in doorways or live in caravans in laybys."

Haddon too finds the monarchy at odds with his vision as a writer. A key theme of The Curious Incident, he says, is the idea "that no human being is inherently inferior to any other. I felt it would have been hypocritical to meet with someone whose job involves being inherently superior to everyone else."

Phillips "believes passionately in the ability of healthy societies to take in and recognise those who are different from them; to enable them to rise to the top, without feeling there's only so far they can go". Haddon would "love to live in a society where no one is seen as inferior on account of who their parents are. But I don't think this is ever going to happen while we have a head of state who gets the job - and the frocks and castles - simply because their father had the job before them."

This year's Commonwealth Writers Prize winner, who is also British, describes herself as a republican too. Andrea Levy, who won for Small Island, her Windrush-era novel of West Indian migration, believes the monarchy "keeps the class system rigid" and "stops us moving on". She was in two minds about seeing the Queen, and adamant that she refused to curtsy, though when she was asked to a big palace reception after winning the Orange prize, "my mother burst into tears; it made her existence. I was surprised, but I understood her life in the Caribbean better." Yet Levy succumbed to "enormous curiosity", and spent a quarter of an hour with the Queen last Friday. "There was bizarre pageantry, but at the end you do sit down with a human being," she says.

The refuseniks stand firm. "I know writers who have met the Queen and found her charming and articulate," says Haddon, "but the idea of one human being having to bow or curtsy to another is one I find offensive." For Phillips, a hereditary head of state is "simply nonsense".

· Maya Jaggi was the British judge for the 2004 Commonwealth Writers Prize.