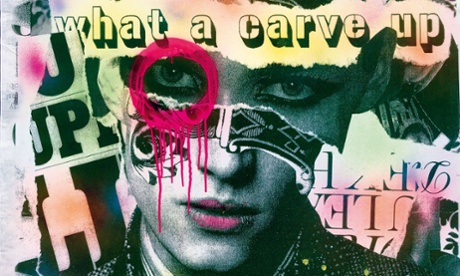

You don’t want to read about happy families at Christmas, feasting and carolling and blessing each other, every one. Whether as a pleasing contrast to your own idyllic circumstance or a toothsome reminder that things could be worse, you want to read about a family who are, by the admission of one of their own members, “the meanest, greediest, cruellest bunch of back-stabbing penny-pinching bastards who ever crawled across the face of the earth” – the Winshaws in Jonathan Coe’s brilliantly plotted and bitingly angry black comedy about privilege and greed, What A Carve Up!

Investigating their misdeeds, and the wartime tragedy that links him to them, is literary novelist Michael, who has been commissioned by dotty Tabitha Winshaw to write a family history that will shake all the skeletons out of their closets. Dreamy and uncertain, Michael comes from a humble background, and is inclined to hide from the world; the Winshaws, on the other hand, are inclined to devour it. There’s banker Thomas, making money out of nothing by speculating on the stock market in the wake of Thatcher’s Big Bang; arms dealer Mark, punting nerve gas to Saddam Hussein; politician Henry, ostensibly left-wing at first but dedicated only to the entrenchment of the establishment and his own advancement; farmer Dorothy, putting profit before health and animal welfare to build a ready-meal empire; Roddy, an art dealer with zero interest in art; and Hilary, a tabloid columnist cynically confecting toxic opinions for a fat paycheque.

Two decades after the book was first published, there are many examples of real-life Winshaws to be found. For a novel so rooted in its political times, it’s shocking – and depressing – how relevant it still is. Coe uses the Winshaws to rail against the marketisation of the NHS, farming malpractice, the shoring up of tyrants abroad and the dumbing down of culture at home – all the carving up of the common good in the pursuit of profit. As Henry says, the trick in government “is to keep doing outrageous things”.

The gloomy fun Coe has at the expense of literary publishing’s decline in fortunes hasn’t dated either (the novel also includes one of the best jokes about book reviewing ever written). Many could rant along today: “Nobody gives a tinker’s fuck about fiction any more, not real fiction, and the only kind of… values anyone seems to care about are the ones that can be added up on a balance sheet”. The 90s saw the rise of the celebrity novelist, and Hilary Winshaw, Michael’s mournful editor tells him, has got in on the act with

‘the usual sort of rubbish… Cheap tricks, mechanical plot, lousy dialogue, could have been written by a computer. Probably was written by a computer. Empty, hollow, materialistic, meretricious. Enough to make any civilised person heave, really.’ He stared ruefully into space. ‘And the worst of it is they didn’t even accept my bid.’”

In some ways, all that seems to have changed over the past two decades is technology (the freeze-frame function on video recorders plays a big part in the book) and the names of chocolate bars (Michael has a penchant for Marathons).

Coe has commented ruefully that readers and reviewers like “to remind me as often as possible that What a Carve Up! is my best novel”, and wondered if that might be because they share its politics. But there is so much more to the book than didacticism. There is the glorious plotting that laces the book tighter than a drum, and any number of wonderful comic set pieces, from the world’s worst tube journey to Michael’s woeful attempts to write a sex scene. There is the mashup of genres, from newspaper reports to a hommage to the golden age of detective fiction. There is the mysterious power of Michael’s childhood obsessions, including space flight, cinema and the Orpheus myth; and of course there are those awful, awful Winshaws.

Insanity runs in the Winshaw family as well as avarice. Who is more deluded: Tabitha, confined to an institution for accusing her brother of murder, or the rest of the family, who put profit before people? “There comes a point when greed and madness become practically indistinguishable,” says Mortimer Winshaw. “The willingness to tolerate greed, and to live alongside it, and even to assist it, becomes a sort of madness too.” As austerity bites and climate change threatens, society looks madder than ever.