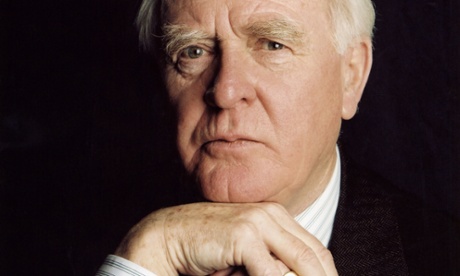

Some of my favourite writing about London is in works of fiction that aren’t primarily about London at all. Examples I keep close to hand include John Le Carre’s famous Cold War stories about his spy character, George Smiley, resident of Bywater Street and operative from a pretend spook HQ in Cambridge Circus. My favourite is Smiley’s People. I’ve read it several times, and parts of it several dozen times. Perhaps it is the current uneasy political and economic mood that’s made me pick it up once more.

Published in 1980 and set in that tumultuous late-’70s period of punk rock, “stagflation” and a fragile Labour government before Thatcherism began, it follows Smiley visiting the spartan West London flat of an elderly Russian defector named Vladimir who had been murdered on Hampstead Heath the night before. Le Carre describes a tired, tattered London of not so very long ago:

There are Victorian terraces in the region of Paddington station that are painted as white as luxury liners on the outside, and inside are dark as tombs. Westbourne Terrace that Saturday morning gleamed as brightly as any of them, but the service road that led to Vladimir’s part of it was blocked at one end by a heap of rotting mattresses, and by a smashed boom, like a frontier post, at the other.

“Thank you, I’ll get out here,” said Smiley, politely, and paid the cab off at the mattresses.

He had come straight from Hampstead and his knees ached. The Greek driver had spent the journey lecturing him on Cyprus, and out of courtesy he had crouched on the jump seat in order to hear him over the din of the engine. Vladimir, we should have done better by you, he thought, surveying the filth on the pavements, the poor washing trailing from the balconies...

He walked slowly, knowing that early morning is a better time of day to come out of a building than go into it. A small queue had gathered at the bus-stop. A milkman was doing his rounds, so was a newspaper boy. A squadron of grounded seagulls scavenged gracefully at the spilling dustbins. If seagulls are taking to the cities, he thought, will pigeons take to the sea?

Shedding chestnut trees darkened the pillared doorway, a scarred cat eyed him warily. The doorbell was the topmost of thirty but Smiley didn’t press it and when he shoved the double doors they swung open too freely, revealing the same gloomy corridors painted very shiny to defeat graffiti writers, and the same linoleum staircase which squeaked like a hospital trolley. He remembered it all. Nothing had changed, and now nothing ever would. There was no light switch and the stairs grew darker the higher he climbed...

He reached a landing and squeezed past a luxurious perambulator. He heard a dog howling and the morning news in German and the flushing of a communal lavatory. He heard a child screaming at its mother, then a slap and the father screaming at the child...There was a smell of curry and cheap fat frying, and disinfectant. There was a smell of too many people with not much money jammed into too little air. He remembered that too. Nothing had changed.

Things have changed a little now. Milkman are harder to find and newspaper boys are almost unheard of. Scavenging seagulls can still be heard and, presumably, seen, but these days the habits of foxes exercise us more. On the other hand, there are still plenty of gloomy private housing blocks where too many people with too little money reside. But maybe Westbourne Terrace no longer provides a good example. Today, a one-bedroom flat there costs well over half a million pounds.

Smiley’s People also contains evocative descriptions of dusty libraries in Bloomsbury, the hinterland of the old docks, and walled gardens next to Hyde Park that everyone pretends do not exist. Treat yourself via here.