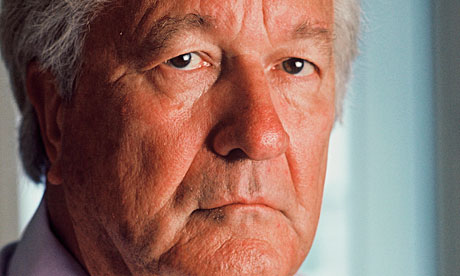

Twenty years ago today, the American novelist William Styron's short but devastating memoir about his depression and near-suicide, Darkness Visible, was published in the UK. In it, he described depression as "a disorder of mood, so mysteriously painful and elusive in the way it becomes known to the self – to the mediating intellect – as to verge close to being beyond description." And yet, then as now, the most striking aspect of Styron's book is just how close it gets to describing the stifling horrors of the illness.

The publication of Darkness Visible helped break the silence around depression, which many suffered in solitude. It also tackled head-on the pervasive assumption that depression is simply down to individual weakness, particularly when it drives people to suicide. And it argued from weathered experience that anyone suffering from depression must not, whatever happens, give up – indeed, its closing pages are profoundly redemptive, offering hope and guidance to anyone who has been affected by the condition.

I should say at this point that when I first picked up Darkness Visible around nine months ago, I was very depressed myself. Not to the extent that Styron describes - he was afflicted by severe, or "clinical" depression – but enough to make me feel acutely sad, anxious and lost. And it wasn't the first time; this has been happening periodically for around 15 years, and has often made romantic relationships, friendships and professional progress very difficult. So perhaps I was primed to be moved by Styron's strangely luminous description of being smothered by depression; but its appeal is by no means limited to those with firsthand experience.

The power of Darkness Visible was immediately clear on its publication. Applauded by critics and clinicians, Styron was flooded with letters from readers grateful to him for describing so clearly an illness whose very nebulousness makes it mysterious to many suffering it – let alone their friends and families. "Out of a great deal of luck and timing, I was able to be the voice for a lot of people," Styron told the New York Times.

At just 85 pages, Styron's account is piercingly concise. It starts in Paris in the winter of 1985, when the author first realised that the melancholy which had dogged him for months was descending into a deep, chaotic depression. Styron remembers his brain feeling "under siege", while his thoughts were repeatedly "engulfed by a toxic and unnameable tide". He goes on to unflinchingly document his descent over several months into a bed-ridden, suicidal trance whose nadir found him minutes away from taking his own life, before he pulls himself back from the brink, and checks into a hospital, where, with the tough, tireless support of family and friends, he slowly recovers.

In some ways, Styron's account has now dated. (For example, he acknowledges that his suicidal impulses were probably magnified by the high doses of benzodiazepines prescribed by his psychiatrist; these drugs have thankfully now been largely replaced.) But its remarkable descriptions of what happens when the mind turns "agonisingly inward" make it as urgent today as 20 years ago. Styron's assertion that "the gray drizzle of horror induced by depression takes on the quality of physical pain" is acutely well-observed. Elsewhere he protests persuasively against the word itself, saying that it totally fails to convey "the howling tempest in the brain".

It is vitally important that we celebrate the anniversary of a book which offers a vocabulary for this illness. The mental health charity Mind recently reported that men and boys are still reluctant to admit to themselves or others that they have a mental health problem; stigma remains acute. Depression affects around one in 10 people in the UK. But speak with psychologists in the NHS and they'll tell you they are braced for higher case loads, even as frontline mental services are being senselessly cut.

So it's encouraging that Darkness Visible has become the founding text of what is now a flourishing genre known as depression memoir. You can feel its reassuring hand on the shoulder of many brave and searching accounts, including Andrew Solomon's The Noonday Demon, Lewis Wolpert's Malignant Sadness, and Tim Lott's The Scent of Dried Roses.

And we need more of them. They continue to break the silence, while expanding our knowledge about an illness that remains essentially mysterious. Few conditions are as idiosyncratic – depression affects people in countless ways, and its causation can never be precisely determined. It's the accumulated weight of decades of lived experience, which have somehow tilted you towards despair. Literary accounts are no replacement for empirical studies or professional services; but they can hold up individual experience in such a way that it catches the light for others watching. They are flashlights in the dark, which can make you feel less alone in depression's deep wood.

Most importantly, what Darkness Visible offers is hope. Its message is this: depression is conquerable. Styron stresses that even if you have reached "despair beyond despair", keep going. Eventually you will be delivered back to the capacity for serenity and joy. It remains as important to repeat that now as 20 years ago – and, I'm sure, will be just as crucial 20 years hence.