For those of us whose foreign-language abilities extend little beyond ordering a cerveza or croque monsieur, the polyglot is to be envied and admired. But the hyperpolyglot, defined here as someone who knows at least six languages and possibly dozens, is a more enigmatic and freakish specimen, rather like a music prodigy or maths whiz. Can some individuals really master a cornucopia of foreign languages when others struggle with the rudiments of one? Are the reported feats of the world's most accomplished language learners rooted in myth or reality?

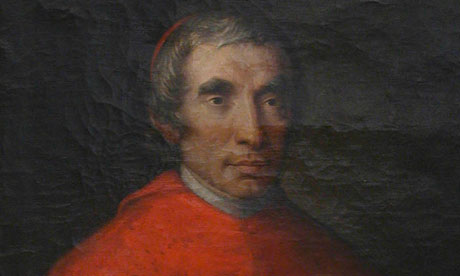

Born in Bologna in 1774, Cardinal Giuseppe Mezzofanti was said to know as many as 70 languages and be capable of switching from one tongue to another as effortlessly as one might slip into a different coat. According to a famous anecdote, Pope Gregory XVI once arranged an audience with Mezzofanti for a group of international students, who tried to bewilder the cardinal by speaking en masse in their own languages and were left stunned when he responded to each student in turn. On another occasion, Russian scholar AV Starchevsky confused Mezzofanti during a meeting in Rome by chatting in Ukrainian; after being invited by the Bolognese to come back in two weeks, Starchevsky was flabbergasted to hear Mezzofanti converse in fluent Ukrainian on their subsequent appointment.

Having since become a byword for hyperpolyglottery, Mezzofanti has attracted admirers and sceptics in apparently similar measure, including those who write him off as a fable. But if his talents are believed to surpass all others, he is not the only individual from past or present linked with extraordinary language proficiency. Emil Krebs, a German diplomat active in the early 20th century, claimed to know 65 languages. Until the late 1990s, Ziad Fazah was down in The Guinness Book of Records as speaking 56 "fluently", but was widely discredited after performing badly in a Mezzofanti-like test broadcast on Chilean television in 1997.

Describing himself as a "monolingual with benefits", author Michael Erard embarks on a globetrotting mission to uncover the truth about hyperpolyglots. Starting in the Bolognese library that houses Mezzofanti's archive, he quickly dismisses any notion the hyperpolyglots of history – including Mezzofanti and English explorer Sir Richard Burton – had complete mastery of all their languages. Nineteenth-century linguists would have been judged largely on the strength of their "receptive" skills, such as reading and translating, instead of the more demanding task of oral communication. When it came to the latter, the nature of exchanges between a cardinal and foreign dignitaries would have ensured Mezzofanti was rarely outside his comfort zone.

What, then, of modern-day hyperpolyglots and the ignominy of Fazah? An encounter with Alexander Arguelles, whom Erard eventually befriends, reveals much about the disposition and abilities of so-called language accumulators. An introvert based in California, Arguelles spends hours each day studying dozens of languages, purely as a labour of love, but can speak fluently in only a handful without any preparation. Other accumulators Erard meets display similar proclivities and skills. While many claim to have an aptitude for language learning, studies suggest no hyperpolyglot can maintain more than seven or eight languages to a high standard at any one time because of working memory limitations. Even multilinguals exposed to many languages from birth are better in some than others.

Erard's book gradually morphs from journalistic inquiry into scientific investigation. The author is treated to an examination of Krebs's brain, preserved for medical research and unusually developed in areas associated with language accumulation. Seeking to establish whether nature or nurture is primarily responsible for language talent, he also meets Christopher, a possible autism sufferer (although never formally diagnosed with the condition) who absorbs languages like a sponge but exhibits some curious shortcomings, including a failure to master syntax. Experiments conducted on laboratory rats in the 1980s showed that spikes in testosterone at important developmental stages caused cells to migrate from the left hemisphere of the brain to the right – the side linked with puzzle-solving and related abilities in humans – creating the imbalance that might lead to autism, dyslexia and even left-handedness among language savants.

Despite indications that some individuals are biologically or genetically predisposed to be extraordinary language learners, however, Erard reveals equal support for alternative explanations. Krebs may have formed additional neural connections by exercising his language faculties so heavily, much as an athlete trains a muscle. Learning a new language may be easier for a polyglot than a monoglot because the former can recognise patterns based on existing knowledge while the latter is starting from scratch. Erard's discovery and ultimate revelation that Mezzofanti, of all people, relied on a method as banal as flash cards might disappoint readers looking for a magic key, but it could spur others to persevere with their own more elementary efforts.

Mezzofanti's Gift is available to buy at ducknet.co.uk