I don't think I'd ever read a proper parody before I stumbled across Bored of the Rings. I was in my early teen years, sulky and gawky and pottering around Swanage on the Dorset coast on what would be the last real family holiday. I'd probably not long since read the actual Lord of the Rings when I was mooching around a bookshop near the front and plucked out this slim, imported paperback.

I was a mass of whizzing teenage hormones and the extract on the flyleaf had me hooked, detailing as it did the seduction of a hobbit-like character by a sensuous elf. I read it through in a couple of sittings on the beach, and by the end of it, if I'd realised the saucy passage didn't actually appear in the book, I didn't care. I'd been introduced to satire.

Bored of the Rings was published in 1969, and as such could arguably be the forerunner of today's sub-genre of comic fantasy exemplified by Terry Pratchett and Tom Holt. But whereas Pratchett's Discworld operates within the logical framework of proper fiction, Bored of the Rings throws those rulebooks out of the window.

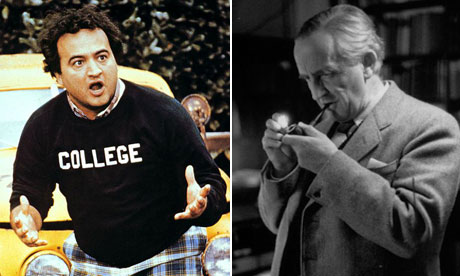

Freshly published in a new edition this month by Gollancz, Bored of the Rings was credited to the Harvard Lampoon – in essence, Douglas Kenney and Henry Beard – which grew into the National Lampoon in the 1970s. Bored of the Rings sits somewhere between the classic US parody magazine Mad and National Lampoon's signature movie Animal House – cruder than the former but not quite as rude as the latter.

Tolkien's three-doorstep magnum opus is boiled down to a couple of hundred pages, with the main characters reinvented as a fairly grimy, down-at-heel set, the simple hobbits of the Shire transformed into greedy, smelly Boggies. Their names reference largely American or long-forgotten brands and slang – Frodo becomes Frito (a brand of crisps, or chips in the States), Gandalf is Goodgulf (petrol), Pippin and Merry become Pepsi and Moxie – soft-drinks.

Others are more obvious and perhaps cringeworthy. Legolas the elf is Legolam, Gollum is Goddam and Bilbo Baggins, of course, becomes Dildo Bugger. Most inspired is folky hero Tom Bombadil's transformation into Leary-esque acid casualty Tim Benzedrine.

Bored of the Rings is, by Gollancz's own admission, "sometimes childish, sometimes rude" but it's also very funny, albeit perhaps less sophisticated than more modern parodies. But Kenney and Beard's respect and affection for the source material shines through.

There's a gag you can appreciate on pretty much every page, and many of them will actually make you laugh out loud. Take Dildo's first encounter with the Gollum-alike: "He would have finished Goddam off then and there, but pity stayed his hand. {itals} It's a pity I've run out of bullets, he thought."

The characters also break the "fourth wall" – Frito rolls his eyes at the beginning of the book and observes that "it was going to be a long epic" and chapter five concludes as the characters "set out with Frito along the rising gorge that led to the next chapter".

There are some "of their time" references that are perhaps wince-worthy; disparaging references to Italians, and a bug-eyed stereotypical African-American skit that is uncomfortable to modern readers but is entirely in keeping with the Brer Rabbit tale it parodies. Arcane references aside, Bored of the Rings stands up well 40-odd years on. Besides, accusations of casual racism are something that the original material has had to sidestep more than once, so perhaps the authors are merely keeping their satire in the spirit of the original.

Who knows what Prof T would have made of it, but it's nice to think it might have raised a smile. And it's refreshing to see a book that lays the cards on the table in its opening salvo: "This book is predominantly concerned with making money and from its pages a reader may learn much about the character and literary integrity of the authors. Of Boggies, however, he will discover next to nothing."