'Dickens was the most gorgeous person you could possibly meet. He was just amazingly affable. Your day would be absolutely made if you bumped into Dickens. More than that, he possessed the power to make you funnier and more attractive. He would laugh so generously that he actually empowered you. What a gift. No wonder that even during his lifetime people knew he was one of the immortals."

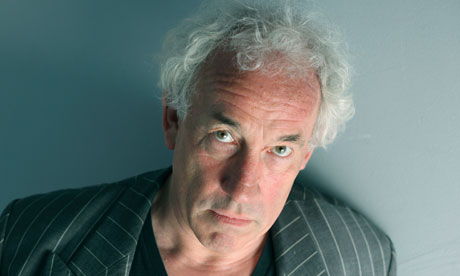

Simon Callow is explaining a lifelong fascination that has led him to write about Charles Dickens, to adapt his work, and to play the man – twice in episodes of Doctor Who alone – as well as his characters on both stage and screen. It is an engagement that reaches something of a culmination next year with the Dickens bicentenary, when Callow will publish a new book about the writer as well as performing a series of one-man shows. But in effect the celebrations have already begun: this year Callow has performed two rarely staged Dickens stories, "Dr Marigold" and "Mr Chops", and is currently appearing at the Arts Theatre, London, in a stage version of A Christmas Carol.

Just like Dickens himself, who used to begin his legendary public readings with a version of A Christmas Carol, Callow is alone on stage from "humbug" to "God bless us, every one", conjuring along the way ghosts, the Cratchit family, the transformation of Scrooge, the prize turkey and all the rest. On top of that, Callow also conjures the person of Dickens. It is a theatrical ebullience that Callow best summed up when writing an introduction to a book about acting. "All our lives in the theatre we have heard this maxim: LESS IS MORE … But very often less is simply less, and more is actually MORE."

On stage Callow made his name in the late 70s with performances in Brecht's Arturo Ui and Shaffer's Amadeus. A few years later he was in the film version of Amadeus, though not playing Mozart as he had on stage. He appeared in Merchant Ivory's A Room With a View and, in perhaps his most memorable film role, as Gareth in Four Weddings and a Funeral, in which he was delighted to play a gay man who died of something other than Aids – "an excess of Scottish country dancing".

As a director and adapter, Callow has done everything from grand opera to one-man shows, and all the while he has conducted a literary career that would be sufficient in itself for most professional writers: it includes reviewing, biographies of Charles Laughton and Orson Welles, a revelatory account of the acting life, a memoir of his intense relationship with the great theatrical agent Peggy Ramsay, as well as guides to Shakespeare, film acting and Oscar Wilde's circle.

His new book will be called Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World, and is essentially an account of the writer "on the stage of life. People have already written brilliantly about the theatricality of the novels," he says, "so rather than do that again it is about his theatricality as a man. His self-dramatisation and the way in which he seemed to live his life in front of footlights."

Callow approached the subject as an actor would a character. "And that is not so easy. How do you comprehend the sheer quantity of things he achieved on an almost daily basis? Part of it is physical. He was a little chap, but he would go up mountains and down glaciers and so on. His physical stamina was extraordinary. The criticism he hated more than anything was that he wrote too much and was uncritical of his own writing. But I'm afraid it's true. He sometimes did just throw down a string of adjectives. But within the best of him is an intense sense of compacted life in the same way that that it is in, say, the music of Beethoven. The life is in the work, and he identified himself so completely with his society and the world in which he lived that he became its living representative. And for that I utterly love him in a way, for example, that I don't love Welles or Laughton, deeply interesting as they are. But all these lives have been fascinating to me in different ways, and a great deal of the work I have done stems from my passion for biography. From an early age that was my preferred reading matter. I wanted to know about other people's lives, and I still start with the obituaries when I open a newspaper. I always want to see where people came from and what they made of themselves."

Callow was born in 1949 in Streatham, south London. When he was 18 months old his father left home, and he was brought up by his mother with the help of his grandmothers. When Callow was nine, he and his mother travelled to what was then Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia, in the hope of a reconciliation with his father. Things did not work out, but his mother stayed on and Callow was sent to boarding school in South Africa for three years before they returned to Britain when he was 12. On the ship home, he recounts in his 2010 memoir-cum-selected journalism, A Life in Pieces, he enjoyed early stage success when he won a fancy dress prize dressed as a cancan girl: "The best thing was being wolf-whistled as I went up to collect it".

He admits he was a slightly odd child whose youth was spent discovering classical music, "so I was a bit deaf to pop in the 60s. But while I didn't set out to be different, I also didn't mind that at all." He and his mother "had a very difficult relationship. We were so temperamentally opposed, and she was a very odd woman. There is something terrible about a quirky parent for a child. I couldn't really understand what she was driving at a lot of the time. But having said that, she also served me incredibly well. She thought a child had to be both disciplined and stimulated. So when we got to Africa, despite the trauma she was undoubtedly going through because it was evident that my father was not sincere in his attempts to revive the relationship, we went on safari and I had to learn about these extraordinary animals. She always made me give an account of myself. I had to be amusing and intelligent and have ideas about things. There was no indulgence. You couldn't be boring. I had to justify my place in the conversation."

Although aware of the potential for emotional damage, Callow says his childhood left him largely unscarred. "There is something essentially sanguine about me, which I am inclined to attribute to the fact that I was born by caesarean section. It must affect you. Most children have to fight and kick their way into the world. I was serenely lifted out. A lot of untoward things have happened to me, but I've usually risen above them."

Most recently he had to deal with his mother's decline into Alzheimer's, and he has written and spoken movingly about both her condition and the practical aspects of care that have forced him to sell his own home to help pay the bills. His openness about his finances matches an openness about other aspects of his life: he was one of the first and highest-profile public figures to come out as gay in the 1980s. "I am a person without secrets. Which might be to the detriment of my art. Artists probably should have some impenetrable aspects of themselves."

It was this impulse to openness that led him to write Being an Actor in 1984. "I wanted to describe the experience as it was happening. I wrote that the power of directors was out of hand, and the balance had been skewed, which wasn't good for acting or writing or performance. Michael Billington said it was a 'tragically misguided conception'. But so many actors wrote to thank me for saying it, and people like Branagh went off and tried a new approach. That wasn't specifically because of my book, but I had articulated something."

He says that coming out as gay in the book was part of the same process. "If I hadn't said anything I wouldn't have been doing the job I had set myself. You couldn't ignore that at that time 99% of gay actors were in the closet. But it was never that difficult for me to say it. I'd always rather liked the idea of being gay, but I wasn't sure I was very well qualified for the job. I didn't think I was attractive enough, and I was very shy about making moves. Some people have a real gift for being gay, and are terribly good at it. That wasn't me. But I have been lucky in having some wonderful relationships."

Callow had found his way to the stage after leaving school in London in 1967. "I actually wanted to be a writer long before I wanted to be an actor. Not because I didn't want to act. But I couldn't see a way in which it would come about." His way in was via a three-page letter to Laurence Olivier, which resulted in a job in the box office at the National Theatre, then housed at the Old Vic. Fired by exposure to theatre, he took a place at Queen's University Belfast, ostensibly to read French but really to act. It was a disappointment academically, but Callow did meet and work with the great Irish actor Micheál Mac Liammóir, whose one-man show The Importance of Being Oscar can be seen as a major influence on Callow's subsequent explorations of the lives and worlds of Wilde, Dickens and Shakespeare. "I did rather fall in love with this form he had invented – the biographical tour. You are the narrator and you impersonate the characters and sometimes you are the subject himself. It's an antidote to those deadening biographical shows when someone comes along and says "I was born in a cabin in Massachusetts …"

After leaving Queen's, Callow enrolled at the London Drama Centre, before making his professional debut in Edinburgh in 1973 and joining the Gay Sweatshop theatre company. Bit parts on TV followed – including an episode of The Sweeney – but his first major success was playing Mozart in the 1979 National Theatre production of Amadeus. "Paul Scofield, who played Salieri, refused point-blank to do interviews. Felicity Kendal was at the height of her fame but had probably given too many interviews, so I was the one who spoke to the press. I didn't really want to be famous as such. I wanted to be well known as an actor in the way that, say, Maggie Smith was well known as an actor, and I still generally avoid premieres and showbiz events. If a movie needs to be promoted I'll do it, but apart from that it never seems like time well spent. What I didn't anticipate coming from this new fame, such as it was, was that I would become a public figure, although it was really inevitable given my compulsive desire to communicate on any number of subjects."

Callow began to write book reviews in which "I simply tried to puzzle things out. I asked what's going on and what is meant. I do it as an actor and I do it as a reviewer." It was his interest in "how things work" that prompted his move to directing. "I love it when I do it, but you shouldn't really dabble at it and I do dabble. I write full-time. But if you only direct every few years then you tend to forget all the things you should anticipate. I have had a few major car crashes, some of them just critical disasters but some actual disasters too." His 1999 revival of the musical The Pajama Game lost about £3m. "You do go around for a while feeling a bit like a criminal. It doesn't matter who is to blame – you as the director are to blame."

As his career has progressed, he says, his view of acting has changed. "While it started as a type of escape, it has now become the exact opposite, in that I'm actually trying to connect to the centre of myself rather than creating a periphery. So my final considered thought on the theory of acting is that it is 'thinking the thoughts of another person'. The thoughts of the writer must pass through my brain and body to come out as something interesting for the audience. And that means I have to bring me to the performance every day. You can't let a performance just do itself." He cites the teachings of GI Gurdjieff (Peter Brook is an even stronger devotee), "who says we are all essentially asleep. So my great job as an actor is to be awake when I'm on stage. Utterly, 100% awake, which then yanks the audience into time-present as well. That is traditional mystical wisdom, but this business of the now is genuinely important and rather exhausting – if you pull it off it does release something rather fantastic."

In practice this means he does not attempt to reproduce the way Dickens conducted his readings. "What interests me much more is trying to make the work completely surprising again. That is very hard to do with something like A Christmas Carol. I'm interested in recreating the innocent ear or eye, so that the work is de-patinated, that it comes to you as fresh as the moment it was written. And what this implies is a search for simplicity. Perhaps simplicity is not something that people think about when they think of my work, and yet that is what I am now striving for."

Over the years he has worked with Peter Ackroyd on Dickens and with Jonathan Bate on Shakespeare. "And then these things are rewritten over and again, because in the end they also have to fit me and so they have to be teased out over time. Being Shakespeare, as The Man from Stratford finally became, is probably my proudest achievement in the theatre. It has been refined and distilled and it is now just itself – a perfect conjunction of form and content. We've been through the same process with A Christmas Carol to make this very over-familiar story work. Looking at the structure of sentences, deciding whether to move a clause, finding a different adjective – it has been a little nightmarish, but part of the joy is in the detailed working with these texts."

Callow's upcoming work includes a first novel and a book of pen portraits of people he has known who have died – "when I thought of the idea it was intended as just a little book, but now it has sadly become a much larger thing". He will also be touring both Dickens and Shakespeare and "has to" finish the third volume of his Welles biography. "And now I can do it, because one way and another my life and my finances have regularised themselves. The problem with writing such a big book is that it takes a long time for not much money. A £25,000 advance paid in three tranches basically means £8,000 for a 700-page book. And taking nothing for granted about Welles in among all the sometimes confusing myth-making is a job that cannot be rushed. But I've never minded hard work. It was my mother who instilled in me that you shouldn't waste a single second. She had no ability to relax and still doesn't, and she now constantly pushes these little blocks around on a tray at her home. When I was young, at the end of every day, she'd always ask me what I had achieved. Even now, if I've had a very nice time with friends, which is exactly what I needed and wanted, but I've done no acting or writing, then I am left with this slight feeling of guilt. It's not really a problem and I certainly get a lot done, but I do admit that I might not be the most relaxing person to go on holiday with."