Diaries: you get one as a Christmas present, start writing it, and continue for, oh, a few days more or less than you go to the gym for the new year. Then you give it up, along with that new dietary regime.

Fictional characters, however – forced by their authors to carry the story, slaves to the process of narrative – tend to be much more reliable. And there's good reason for the format's popularity in novels. At the most basic level, it means you can have a first-person narration without the protagonist knowing what's going to happen (although going out on a dangerous adventure is slightly less exciting, because the diarist definitely got back safely to write it up).

Fictional diaries have been amusing and entertaining us since the modern novel's early days. Here are some favourite examples.

Pamela

Samuel Richardson's Pamela (1740) is usually described as an epistolary novel. But our heroine also writes a journal, and then sews it into her underwear for secrecy (she describes it as "in my undercoat, next my linen"), so she is wearing it at all times. It is hard to imagine a better metaphor for the history of women and their writing – and, perhaps, women's diaries – over the past 250 years.

Wuthering Heights

It's easily forgotten, but Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Brontë has a skeletal framework of a diary: "I have just returned from a visit to my landlord … Yesterday afternoon set in misty and cold". Mr Lockwood will learn about true emotion day by day as he finds out and writes down the story of Heathcliff and the Earnshaws.

What Katy Did

Susan Coolidge's 1872 book What Katy Did, beloved by generations of children, contains a scene where the older siblings laugh at young Dorry's diary, with its repeated entry: "Forgit what did." Many of us could empathise with that, though we can't hope to inspire, of all unlikely things, a Philip Larkin poem about unkept diaries called Forget What Did, the title taken from Dorry.

Diary of a Nobody

George and Weedon Grossmith's Diary of a Nobody, 1892, first appeared in the humour magazine Punch – but is better than that makes it sound. It has never been out of print, and is full of fascinating details of daily life as well as excruciating class warfare and British embarrassment tropes. Maybe not a book to be translated around the world, but the jokes have lasted longer than the currency: "I am a poor man, but I would gladly give ten shillings to find out who sent me the insulting Christmas card I received this morning." True fans are laughing after the first few words of Charles Pooter's expressive complaint.

Dracula and 1984

Diaries form a key part of books that aren't automatically associated with them: three different diaries are used for the narrative of Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897). In a recent Guardian piece I was looking for anti-anachronisms, book references that seem out of their time but are unimpeachable, and a reader splendidly pointed out that a key character is busy taking photos of Dracula's future home with his Kodak, just to jolt you into the late 1890s. And in George Orwell's 1984, Winston Smith starts his rebellion by writing a diary, even though he's not sure what date it is.

The Man in a Brown Suit

Diaries are very handy for murder story writers, and the record of the day's activities might be hiding as much as it reveals with a careful use of words – "I did what little had to be done" is a well-known euphemistic entry, but we'll keep the name of the book hidden for fear of spoilers. And a word for Agatha Christie's The Man in a Brown Suit, where part of the book is the diary of MP Sir Eustace Pedler, a very entertaining slice of his life amid the rather Peg's Paper adventures of the heroine, and laugh-out-loud funny in places.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and Diary of a Provincial Lady

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925), the diary of the beautiful Lorelei Lee, was written by a brunette – Anita Loos – who was annoyed not about silly or gold-digging ladies, but about men's stupidity about women. It's still very funny and clever, and still has points to make about relations between the sexes. And EM Delafield's Diary of a Provincial Lady (published 1930) seems artless and real but is actually a very careful and enduring work of fiction.

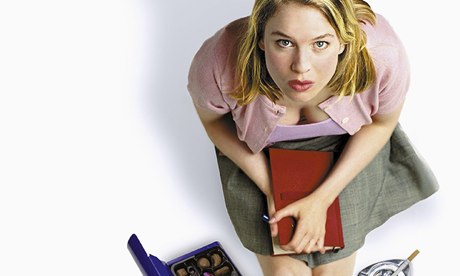

Bridget Jones's Diary

The same could be said about Helen Fielding's Bridget Jones. Bridget Jones's Diary (1996) is well known to be based on the plot of Pride and Prejudice, but in fact reminds me more of The House of Mirth, Edith Wharton's 1905 classic of singleton life and problems, with Lily Bart transported to a kinder and funnier time. Like most of the books mentioned, Bridget Jones's Diary contains wonderful social observation: if the world were to end, you could recreate the Britain of the 1980s and 1990s from the Fielding books, Sue Townsend's Adrian Mole, and Posy Simmonds' Mrs Weber's Diary, the marvellous cartoon strip that first appeared in the Guardian.

I Capture the Castle

Dodie Smith's I Capture the Castle (1948) is the iconic diary book for young women, from its beginnings in the sixpenny notebook to the last desperate words scribbled in the margins of Cassandra's two-guinea book (more outdated currency). The diary format is very popular in books for teens – Diary of a Wimpy Kid is the bestselling example of the moment, and there's also Meg Cabot's The Princess Diaries, Louise Rennison's Angus/snogging/thongs books, all those fictional diaries of historical figures, the Spud books of John van de Ruit, and many others. Young people like reading the details of others' lives, and get something more from diaries. As my son put it to me: "We take black joy in other people's misery; it's good if the diarist is slightly worse off than readers, we find it encouraging. Diaries are meant to be truthful, so writers reveal that they are not as pleased with themselves as they appear on the surface."

Some of these diarists – looking at you, Mr Lockwood – are forgotten. But others are standout characters, people whose names are part of the national culture. Everyone knows what being a bit Bridget Jones means; historian David Starkey compared Edward VI to Adrian Mole; Pooterish is a widely understood adjective. Which other fictional diarists have become part of our lives?