Helen Oxenbury, illustrator

I first heard the story when the Scottish folk singer Alison McMorland recorded a traditional song about a bear hunt and asked me to design the record cover. By coincidence, Michael Rosen and his editor knew the song, too, realised it would make a good children's story and, without knowing about my record cover, asked if I'd do the illustrations.

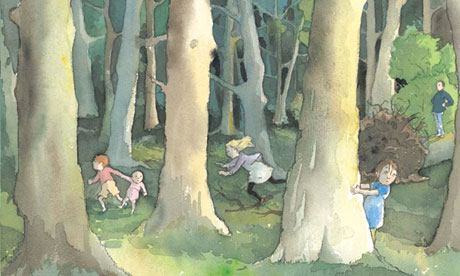

What's wonderful about it is that nothing is described in a way that restricts you. Michael had said he envisioned it as a king and queen and jester setting off to hunt a bear, but I immediately saw it as a group of children. Everyone thinks the eldest one is the father; in fact he's the older brother. I modelled them on my own children. I didn't want adults around because they tend to stilt the imagination. The dog in the pictures was my own dog.

Michael and I didn't meet until after the project was finished. He is the last person to inflict ideas on people: he gave me a free hand. Usually I submit preliminary sketches that are made up into dummies, but for this book I did it all in one go. I got so involved I didn't want to break off to show anyone.

The structure of the story was quite challenging. Finally, I came up with the idea of having black-and-white drawings when the children were contemplating an action, and colour when they were actually doing it. I modelled the muddy scenes on the Suffolk mudflats where we have a boathouse. The rocky beach where the bear's cave is was inspired by a holiday in Druidstone in Pembrokeshire.

I'm a terrible people-watcher. I go to a cafe every day, and sit and watch passers-by, and I draw on this remembered gallery of postures and expressions when I'm working. The great challenge of illustration is how to convey emotion economically.

It occurred to me three-quarters of the way through that the bear was all on his own in the cave, and might have wanted some company rather than to eat the children. I modelled his posture on the final page on a friend who had depression and whose shoulders dropped when he walked. He actually recognised himself and the original now hangs on his wall.

Michael Rosen, writer

The story seems to have been a folk song that circulated around American summer camps, sometimes with a lion instead of a bear. I heard it first in the late 1970s and started to put it into my one-man poetry show. The editor of Walker Books, David Lloyd, saw me perform it and said it would make a great book. I said that he should write it down. He said I should. I said that he should. He said that I should. So I did.

But the way I performed it didn't work, and it wasn't long enough. So I invented some words for the sounds of going through grass ("swishy-swashy"), or mud ("squelch-squerch"). I added a forest and a snowstorm.

About 18 months later, I was taken into a darkened room and in the middle was a table, and on the table a pile of large homemade sheets of thick paper divided by coloured tissue. The editors peeled back the sheets, and I was stunned. First, they were such beautiful pictures. Second, I couldn't figure out what they had to do with a bear hunt. It looked like a family having a holiday in Cornwall. If I had had any image in my mind, it was some kind of street carnival with a bloke in a bear suit. Helen's pictures were something completely different.

The editors said this was one of the most amazing books they had ever seen. And I confess, I didn't get it. I thought they were amazing pictures, but I couldn't figure out how it would work as a book. But I trust illustrators and editors to make books. That's not what I do.

The book came out, and it caused a massive stir, and I had to listen to people to hear why. What brilliant, clever Helen and the editors "got" and had created is that special thing that pictures books can do – which is to narrate different stories in print and in pictures. The family saga isn't in the words. The words were designed for a kind of play-song that you act out as you sing it. The book is an insight into a drama being faced by what is actually quite a vulnerable group: five children, a baby and a dog. Are the black-and-white pages "reality", and the colour only what is in their imaginations? The end paper shows a bear who is humanoid. He/she is clearly not very happy. Is that because he/she wanted to play? When the family dash home and all pile into bed, are they really regretful? Or was it all a family game? This all comes from Helen's imagination: it's nothing whatsoever to do with me. I enjoy and admire the book almost as an outsider.