At the first bookstore I worked in, The Great Gatsby wasn't a classic. Fitzgerald slugged it out in general fiction, side by side with Faulks and Fleming. Fleming wasn't even in crime and thrillers; no, James Bond languished in fiction too.

These decisions, as is the case with all bookstores, had a lot to do with space issues, but our own prejudices came into it. The usuals – Homer, Dostoyevsky, Austen – had at least half a shelf each in classics, while other authors, arguably of the same calibre and importance – Vonnegut, Conrad, Kesey – were kept in fiction.

Undoubtedly important as a figure of his time and of the western literature canon, Fitzgerald just wasn't dead enough or prestigious enough for us to put him in classics. We weren't one of those bewilderingly elitist bookshops that insist on keeping a "literary fiction" section separate, but we were still dictating how customers saw books for the sake of our own reading tastes.

In another shop I worked in, we avoided the issue by defining the "classic" chronologically: anything written before 1960 was kept in "classic fiction" and everything written after went to "modern fiction". But then there were the problem authors, the ones who straddled the two periods. Mary Renault, Gore Vidal and Isaac Asimov skipped over the fence depending on who put them in the system.

Then, because publishers must toy with us, there are "modern classics". Enjoyable oddballs such as John Kennedy Toole and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry get the attention they deserve with this label but meanwhile, Morrissey managed to get his biography published as a Penguin Classic - a move justified by Penguin because it was "a classic in the making".

Like Morrissey, some customers feel their reading choices are more admirable if they come from the classics shelf. I remember one woman snapping, "I refuse to believe that you only have four of the brilliant JD Salinger's books, your classics section is appalling." We had to break it to her that JD Salinger had only written four books. ("The next one comes out in 2060," we told her cheerfully).

After five years selling books, I find the word increasingly meaningless. Unavoidably, booksellers and publishers are gatekeepers, making these decisions to suit their market and make their product easier to buy. What one person regards as an outstanding example of literature, another will consider drivel. The label "classic" is increasingly bandied about with wild marketing abandon. As a bookseller specialising in modern fiction, I look at a lot of new releases with a slightly jaundiced eye. These days any amiable-looking book garlanded with just one or two admiring reviews looks positively rubbish.

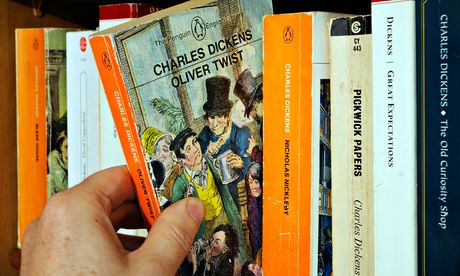

Reading forward, what will stand the test of time? Which current authors will, like Dickens, come to dominate whole shelves, and who will be remembered for only one book? In a year or decade, will genre-hoverers such as Burgess, Kesey, Vonnegut and Bradbury be officially elevated to classic status? That's a burden for future booksellers. At least they won't have to shift shelves online.