RA Lafferty might just be the most important science-fiction writer you've never heard of.

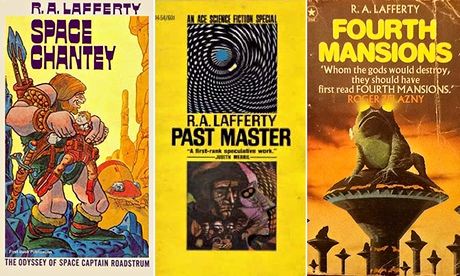

Raphael Aloysius Lafferty – RA for the byline, "Ray" to friends – was born on 7 November 1914 but, centenary year aside, what singles out Lafferty's work from the legions of forgotten paperback SF writers is the sheer absurdity of much of his output and the singular marriage of fable, comedy and fantasy that underpins his writing – including his novels Past Master, Space Chantey and Fourth Mansions, and his huge body of short stories.

Take his 1969 novel Fourth Mansions, a tale of rival world-spanning conspiracies duking it out to shape mankind's next level. Like much of Lafferty's work, Fourth Mansions is infused with his strong Catholic beliefs, his love of mythology, and a darkly comic flair:

There was a young man who had good eyes but simple brains. Nobody can have everything. His name was Freddy Foley and he was arguing with a man named Tankersley, who was his superior.

"Just how often do you have to make a total fool of yourself, Foley?" Tankersley asked him sharply. Tankersley was a kind man, but he had a voice like a whip.

"An enterprising reporter should do it at least once a week, sir, or he isn't covering the ground," Fred Foley said seriously.

There's something of the Irish comic tradition in there, the absurdity and surreality of Flann O'Brien, author of The Third Policeman.

"I agree," says the author Neil Gaiman. "And there's kinship with the American tall tale tradition, and with GK Chesterton. But they are all only cousins. There's nothing close to Lafferty – nobody with the gravitas about things that were light, and the antigravitas about important heavy things."

Lafferty was born the youngest of five children, in Iowa. When he was four, the family moved to Oklahoma, where Lafferty lived until his death, at 87, in 2002. He had more than 20 novels and more than 200 short stories published – success that began relatively late in life, from when her was 46 (he worked as an electrical engineer until 1971 before turning to full-time writing). After a series of strokes in the early 80s, he retired. He lived much of his life with his sister, was afflicted by drink problems and died unmarried.

Gaiman has been a Lafferty enthusiast since he was nine, and discovered the writers' work in various anthologies. He attempted a story in Lafferty style – Sunbird, in his collection Fragile Things – which he said proved to him "mostly how much harder" the style was than it looked.

"What drew me to his work? The narrative voice, I think," says Gaiman. "The way he'd construct a story – unlike the way anyone else did it. The peculiar rightness of his worldview, and the topsy-turvy nature of it. The sentences."

A few years after his initial discovery, Gaiman struck up a correspondence with Lafferty. He remembers: "I sent him a Lafferty pastiche I had written, and he was not rude about it. But he was encouraging, and informative, and took me very seriously, which is good, because I was about 20 and took myself very seriously as well."

There's the sense that Lafferty was outside the mainstream, the SF establishment, ploughing his own absurdist furrow. He was nominated for several Nebula awards but never won one; he managed to share a Hugo award for best short story in 1973, with Frederik Pohl and CM Kornbluth.

You can find one or two short stories online; Slow Tuesday Night is a wonderful example, in which humanity is gifted the ability to make literally split-second decisions, affording them several careers, marriages and lifetimes in a single night. It begins, and ends, with a beggar accosting a couple:

The panhandler was Basil Bagelbaker, who would be the richest man in the world within an hour and a half. He would make and lose four fortunes within eight hours; and these not the little fortunes that ordinary men acquire, but titanic things.

"Lafferty himself said his short stories were better, but his novels had more to say," says Andrew Ferguson. "The stories are always worth going back to, but it's the novels on which his long-term literary reputation will rest."

Ferguson is a PhD candidate at the University of Virginia, and along with Gaiman's championing he's one of the reasons Lafferty is perhaps being pulled back from the brink of total obscurity – he's writing a biography of the author for the University of Illinois Modern Masters of Science Fiction series, and will chair a panel on Lafferty on 14 August at Loncon, the World Science Fiction Convention, being held at London's Docklands.

Ferguson says: "It may be a bit of a cliche, but there's really nothing else out there comparable to him. He's one of the distinctive prose stylists in the genre: you can tell a Lafferty story within a sentence. He's a very funny writer, in a field that has often taken itself way too seriously."

Curiously, though largely out of print in the west, the writer is big in Japan, says Ferguson, where "Lafferty has remained popular for decades ".

This year Centipede Press published a limited-run collection of Lafferty short stories – The Man Who Made Models – which sold out almost immediately. Wouldn't it be nice, though, to have Lafferty available in a more mass-market edition, especially for his centenary year?

Ferguson says: "I'm hoping the Centipede Press editions get licensed for a more affordable edition eventually. I think there'd definitely be readers for a big best of Lafferty retrospective."

That's something Gaiman would like to see, too : "I'd love to see a Complete Lafferty in print. I used to give people his short story collection Nine Hundred Grandmothers, until one day it was out of print and gone."

It's hard to say why, if Lafferty was so brilliant – which he was – he's virtually unknown. David Langford, the noted science-fiction commentator, wrote in his regular SF news bulletin Ansible, after Lafferty's death in March 2002: "The World Fantasy Convention belatedly did the decent thing and honoured RA Lafferty with its lifetime achievement award in 1990. But the SF world never honoured him enough. Major publishers abandoned him in the mid-80s: Lafferty was just too dementedly brilliant for them."

Perhaps what were once perceived as his weaknesses in publishing terms should be seen as Lafferty's strengths. After all, Lafferty's most accessible and widely read novel, Space Chantey, is a psychedelic, Homeric odyssey in which space captain Roadstrum leads an expedition to the pleasure planet Lotophage, where the immortal houri Margaret tells him, very wisely, that "there are worse places to live than in tall stories".

• RA Lafferty's friends called him Ray, not Ralph as an earlier version of this article suggested. This was corrected on 13 August 2014