Like all authors, I have a simple plea: read my book before talking about it. It is clear that few of those discussing it in newspapers and on the web in the past few days have actually done so.

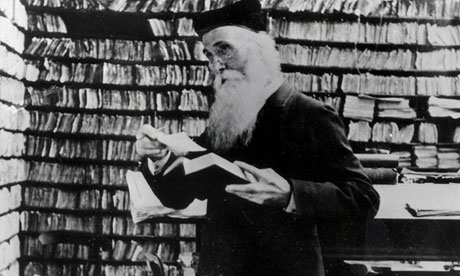

Words of the World: A Global History of the Oxford English Dictionary tells the story of how the 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary has been, since its beginnings in the mid-19th century, a truly global dictionary. By this, I mean two things. First, that the earliest editors, James Murray and others, admitted surprisingly large numbers of "loan words'" (words borrowed into English from other languages) and "World Englishes" (words from varieties of English around the world) into the dictionary. Secondly, that Murray called on readers from all around the world to provide those words for his team to consider, edit, and include in the dictionary. Murray was ahead of his time: OED was the original Wikipedia.

Oddly, attention in the press has all been focused on the work of an editor from the 1970s, Robert Burchfield, and his deletion of some of those non-British words (which was a small section in a 240-page book). Some journalists have even suggested that Burchfield did this deleting surreptitiously or covertly, which is a ridiculous claim, and not one I made. Nor do I ever attribute mendacity to Burchfield, who was the chief editor of the OED from 1957 to 1986; in fact I warn against that twice.

Yes, it was odd that Burchfield deleted 17% of the loanwords and World Englishes from the 1933 supplement because once a word gets in the dictionary, the policy is that it does not leave. But even more surprising was that the words were there in the first place. Their presence in the dictionary is the discovery of the book! Why? Because there has been a consensus view over the past 40-odd years that the early editors were Anglocentric dons who treated these words "almost like illegal immigrants", to borrow Burchfield's own phrase.

This is a "good news" book about the early editors of OED and their surprisingly positive and pioneering attitude to words entering English from around the world; it is not a "bad news" story about Robert Burchfield. The early editors – James Murray, Henry Bradley, Charles Onions, and William Craigie – included far more foreign words and World Englishes than we previously thought.

What's more, they were criticised by their 19th-century contemporaries for including such words. I found letters, slips, and reviews in the OED archives showing that reviewers, consultants, and the delegates of Oxford University Press (the OED editors' bosses) put pressure on the editors to keep out of the dictionary the "outlandish words" that were "corrupting the English language". The early editors ignored these criticisms and pressures, and kept putting in the loanwords and World Englishes. It is therefore ironic that by the second half of the 20th century, they were being criticized for leaving them out. I wanted, in my book, to give them their due.

I have devoted my life to writing dictionaries and working on Oxford Dictionaries. The sections of my book on Burchfield were written while I was an editor on the OED. My colleagues there read and re-read the chapters many times.

I admire Burchfield and his contribution to 20th-century lexicography greatly, and would never want to be regarded as responsible for the vitriolic comments about him that are being thrown around blogs at the moment. So please, read the book, and let the words speak for themselves. As Herbert Coleridge, the first editor of the OED, wrote in 1857: "Every word should be told to tell its own story – the story of its birth and life, and in many cases of its death and even occasionally of its resuscitation."