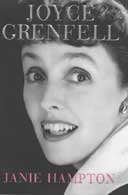

Joyce Grenfell

by Janie Hampton

352pp, John Murray, £20

There is a popular notion at the moment that where the lives of celebrities are concerned, the public has a right to know everything. The daily rags plague the citizens of Britain with endless detail about how many martinis Anne Robinson once drank, or why Geri Halliwell may eventually suffer colonic congestion. It's not that I am not interested in celebrity, it's just that there are very few of the genuine article around. True show business stars are as rare a commodity today as erudition from John Prescott.

If, however, you want a benchmark for true talent, then starting with Joyce Grenfell is about as good as it gets. Born in 1910, she lived in an age of cocktail parties and tennis played on private lawns. A time populated by people called Reggie and, in fact, Joyce. A lifestyle which disappeared about the time the word "lifestyle" arrived to describe it.

Joyce grew up around money and privilege. She was a debutante, and "came out" in 1928, something which today has an entirely different ring about it. Her autobiographies whet the appetite for detail about her life, for they are as complete in what they don't say, as in what they do. These are books in which Joyce clearly wrote about the life she wished she had had. They leave the impression of a jolly schoolgirl springing though a daisy field of joy, while leaving out anyone she didn't like, and hardly mentioning bothersome things like the Blitz.

Janie Hampton would seem to be ideally placed to fill in the gaps in her new biography of the great Grenfell. An old family friend, she has had access to letters and papers which might reveal a greater depth to this funniest of women. To begin with, there is plenty of the straightforward stuff: tales of Joyce's mother, Nora Langhorne, the daughter of an American railroad millionaire who was once engaged to two brothers and their friend at the same time; stories about her redoubtable aunt, Nancy Astor, who was still doing cartwheels into her 60s; and reminiscences of Joyce's husband Reggie, who celebrated finally being alone with his bride-to-be after two years of courting by giving her a bag of sticky toffees.

It's not a bad book if you want detail about Joyce's life. You can learn the names of all 15 people who acted as bridesmaids and pages at her wedding, as well as other events Joyce "enjoyed that year". I just don't know if you will laugh or, worse still, like Joyce any more at the end. I know she lived in a different era, but I came to the conclusion that she and I would not have toured well together.

In her first professional show, Hampton tells us that Joyce "did not adjust to the 'complete lack of standards' of her colleagues in the company, and regretted that they did not go to church or read books, and that many of them were homosexual." Here Joyce and I would have parted company, as that list includes the main reasons for going into show business in the first place.

It gets worse. For all her skill at observing ordinary people, Joyce seems to have been rather grand in life. While touring in Algeria during the second world war, if Joyce didn't get the performance conditions she required she deliberately "became 'altesian' from the French altesse, as in 'Your Highness' - and would make clear her displeasure by becoming taller and more distant." Oh dear, as she might have said, how horrid.

I've given the book to our local charity shop as a tribute to how incredibly kind and generous Joyce was to friends and strangers. I still marvel at the woman who had better timing than a Swiss clock, but in the end it wasn't Joyce I fell in love with, but her mother. Apparently, Nancy Astor invited all the great and the good to Joyce's wedding, while Nora asked her favourite London cabbie and the "one-legged man who sold gardenias outside the Berkeley hotel in Piccadilly". Now, we really would have got on.

· Sandy Toksvig's The Gladys Society is published by Little, Brown