It’s obvious to say that many would be in awe of David Malouf’s career as a writer, speaking at the Sydney writers’ festival in his 80th year. What the audience really take away from his discussion with Tegan Bennett Daylight, however, is an awe of his life as a reader.

Growing up in Brisbane, he was eight when he first read Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, before his father bought him the complete works at aged ten. Since then, he says, he must have read each play “hundreds of times,” and yet, especially when watching Shakespeare in performance, Malouf continues to find lines he has never heard before. “There is nothing more extraordinary to finding your way into the mind of Shakespeare,” he says, still filled with awe. Shakespeare is, in Malouf’s estimation, the greatest writer the world has ever seen.

When he was 12, he tells us how he “read a whole bunch of books that changed my life.” Laughing, he relays these aren’t the books you would think typical for a 12-year old boy to find life-changing: Wuthering Heights, Vanity Fair, Pride and Prejudice, Persuasion, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. These books, he says, “kept telling me the most extraordinary things about the world, and I couldn’t wait to grow up and get into it.”

While Shakspeare may be the world’s greatest writer, the Iliad, says Malouf, “is the greatest piece of writing ever offered to us.” His 2009 novel, Ransom, is a retelling of part of the Iliad, and in writing it “I wanted to be a storyteller of that level,” he says, “but also raise the question of what storytelling is.

“How extraordinary for someone, right at the beginning of our culture, to throw that down and say ‘match that.’”

From Australian literature, he has been influenced by Frederick Manning’s The Middle Parts of Fortune, Kenneth Seaforth Mackenzie’s The Young Desire It, and Patrick White’s The Aunt’s Story. Of these writers, says Malouf, although they’re not always writing about Australia or Australian characters, “their ‘Australianness’ is absolutely taken for granted, and absolutely present.”

The session, too, spoke much to Malouf as a writer. He talks of writing a novel like training for a race (“you’ve got to do it every day”), of learning to listen as a writer (“you’ve got to not speak for [the novel], because if you do you’re shutting out their voice”), and why his books couldn’t be turned into films (“they’re all interior; you can’t translate that to the screen. Almost nothing happens”). But still, it is easy to feel almost the whole week of the festival could happily be filled with Malouf offering his reading suggestions, and detailing how those books have shaped his life.

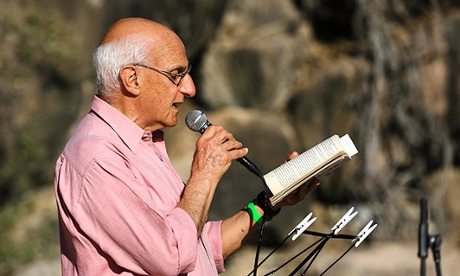

He is not, however, a reader of his own work. After he reads to us a passage from his 1993 novel Remembering Babylon, Daylight asks Malouf if he remembers writing it. “No,” he simply answers, to laughs from the audience. “I think letting [your writing] go is really important,” he says; the last time he reads his work is often the “painful” period of doing proofs.

It is the reader who Malouf writes for, and it is only the reader who can ever truly understand a piece of writing. “The only person who has never read the book is the writer,” he says. “There are things in a book the writer can’t see.” The reader, however, comes in with fresh eyes: they see new ideas and make new connections.

After his work is published, he says, “the book belongs to the people that it was always actually intended for. The book has to go out and find its own friends.” Judging by the audience at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, Malouf’s books have found themselves a very appreciative collection of friends indeed.