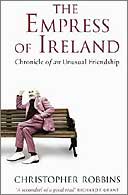

The Empress of Ireland

by Christopher Robbins

400pp, Scribner, £15.99

When, some time in the mid-1970s, my friend Malachy told me that he had found lodgings with Brian Desmond Hurst, I was mightily impressed. Listening to the Warsaw Concerto on a more than usually crackly 78 had been one of the formative musical experiences of my life, so much so that I had taken the trouble to track down the film from which it came, Dangerous Moonlight, with Anton Walbrook. Preposterously romantic, hair tumbling over his noble brow, moustache quivering with sensitivity, the great Austrian actor passionately pounded the ivories while the eponymous moonlight washed over him, dangerously.

The director of this glorious farrago was Brian Desmond Hurst, and I had been surprised to discover that he was responsible for not only this masterpiece of the higher schmaltz, but also the perennial Christmas Carol with Alistair Sim, Malta Story, Tom Brown's Schooldays, The Shadow of the Glen and The Playboy of the Western World. No mean curriculum vitae. So Malachy's new landlord was quite somebody.

"Oh he is," said Malachy, "but he's a terrible old queen." This seemed perhaps not entirely ideal, since Malachy, hitherto a bit of a terrible young queen himself, was about to enter the priesthood. "Oh, but he's awfully religious too," he said, and invited me round to Kinnerton Mews to have a look for myself at the curious array of shrines with which the master bedroom was decorated - one for virtually all the great faiths, with a specially elaborate one for St Theresa.

The presence of these various deities and saints must have provided a piquant contrast to the legendarily pagan sexual practices still vigorously engaged in by the octogenarian director. It was the 70s, and there were still secrets; gay life, only recently freed from the shadows, was still very much a cloak-and-dagger business. Hurst was a sort of central switchboard to those, of all ages and classes, who needed to be discreet. Among them was a distinguished theatrical knight, who was apparently always dropping by in search of a great deal of Scotch whisky and a quick spot of GBH.

I leapt at the opportunity to meet Hurst in person, and finally made it to one of the less louche soirées, where the guests consisted of actors, writers, models, musicians and one or two young men of no specific occupation but considerable testosterone levels. They sat around rather awkwardly, throbbing with sexual potential. Hurst was absent, though much spoken of. Without thinking about it, I found myself sitting on a large wing-backed chair. As if in a fairy tale, a terrible hush descended on the room, the crowd parted and suddenly standing in front of me was a tall, stooped, red-faced old man with piercing eyes and a pair of eyebrows like white flames. "Off," he said, quietly enough, but I leapt away as if he'd cursed me to all eternity. After that I didn't have the courage to speak to him, but watched him unexpectedly beguiling his auditors into roars of laughter.

Soon after I had to leave, Malachy disappeared into the monastery and I never saw or heard of Hurst again. I tried to find out more about him, but the reference books were of little use beyond stating the bare facts of a career which started in Hollywood, where he had been an art director, later becoming John Ford's assistant, then turning out 20 or so films, most of which were unremarkable, but some of which (the ones mentioned above) were quite superb. Only recently, I discovered that he was the model for the character of the vicious old faggot Maurice Hussey in Rodney Ackland's cult play Absolute Hell (not so long ago revived by the National Theatre), but Hussey is an angry caricature born out of deep personal dislike and sheds little light on his evident talent and originality.

Hurst's last years were unproductive, though one of the most touching things Malachy told me about him was that he was in permanent preparation for a biblical epic of some sort, to which end he was always recruiting pretty young actors to audition for angels. At first Malachy had assumed that there was some kind of sexual motive (though pretty young men were not at all Hurst's tasse de thé), but, having assisted at one or two of the auditions, he reported that they always broke up because Hurst would become so moved by hearing them read that he would start to sob and be obliged to adjourn the audition.

This and many other aspects of Brian Desmond Hurst have haunted me over the years, so it is impossible to exaggerate the excitement I felt in discovering that the screenwriter of that very putative biblical epic (actually the story of the nativity, called Darkness Before Dawn) had written a book about him. And magnificent it is, too, a consummate and classic portrait of one of the great picaresque personalities of the 20th century, which will, I have no doubt, guarantee his immortality.

Christopher Robbins's method is of chronological revelation - we learn about Hurst as Robbins does, and he takes us deeper and deeper into his world, his history and his nature, stripping away the layers like peeling an onion. It is no surprise that one of Hurst's best friends was the legendary blagueur and international conman Gerald Hamilton, upon whom Christopher Isherwood based his Mr Norris; Robbins's relationship with Hurst is deeply similar to that of William Bradshaw (Isherwood's alter ego) and Norris, and the book offers a kind of joint portrait, with Robbins constantly outwitted and wrong-footed by his outrageous partner, whom he comes, in some peculiar way, to love.

Hurst, like Norris, was given to magniloquent utterances about himself, elaborate in locution, full of a sort of arch wickedness: "Some people have asked me over the years whether I'm bisexual. In fact, I am trisexual. The Army, the Navy and the Household Cavalry." His manifold contradictions - sexually insatiable (anything in uniform), naively religious (he relied on St Theresa to get him whatever he needed), intellectually highbrow (Finnegans Wake was his favourite book), but full of a kind of penetrating folk wisdom, sometimes harshly dismissive, often sentimentally tender - are brilliantly noted and exemplified as Robbins comes increasingly to understand that the film will never be made, despite recces to Malta, long script sessions in Tangiers, recruitment of directors and investors, and encounters with stars. Instead he starts to act as Hurst's amanuensis on an autobiography, which elicits extraordinary accounts of a childhood in working-class Belfast and war service in Gallipoli; eventually, though, even the autobiography begins to seem unreal.

They drift apart, the process perhaps encouraged by Hurst, who begins to seem more and more a Falstaff figure, pushing Robbins's Hal away from him towards independence and manhood. At the very end, Robbins glimpses a Hurst seen by no one else: "The roguery and the sophistication had evaporated, replaced by a childlike openness that was kind and simple and pure. I was blessed with a look of the utmost gentleness. Saintly would have been the word to describe it, had I been more Christian."

The Empress of Ireland is a fine book about the liberating friendship of opposites, about the masks of personality, about the coming of wisdom. It is also endlessly funny and brilliantly colourful. Something of a masterpiece, in fact.

· Simon Callow's Orson Welles: The Road To Xanadu is published by Vintage.