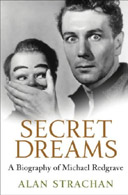

Secret Dreams: The Biography of Michael Redgrave

by Alan Strachan

448pp, Weidenfeld, £25

Alan Strachan is right to point out that when John Gielgud's obituaries were written, and his place in the theatrical pantheon assessed, Michael Redgrave was inexplicably omitted from the list of Britain's greatest 20th-century actors. The fine and judicious biography he has written does an important service in restoring a major figure to its rightful place in the theatrical landscape. It must, however, be said that both the career and the man emerge if anything somewhat more enigmatic than they were before.

Inevitably, Redgrave, whose last major creation was Jaraby in The Old Boys (directed by Strachan) at the Mermaid in 1971, is remembered by fewer theatre-goers than the other great actors who all had Indian summers well into their 70s. His distinguished body of film work - including superb performances in The Browning Version, Dead of Night and The Stars Look Down - is perhaps better known, and fortunately now includes the television film of the Chichester festival production of Uncle Vanya which preserves his nonpareil performance in the title role, generally regarded as the crowning glory of his work in the theatre.

If nothing had survived but this one performance, both electrifying and heart-breaking, he would on the strength of it have joined the ranks of the Immortals. The character's life is inhabited with profound complexity but also a kind of transcendent poetry: absolutely real but on an epic scale, the reality of life itself, not merely of one life. His co- star, the director of the production, is Laurence Olivier, whose Dr Astrov is itself a brilliantly achieved, deeply felt performance. But Redgrave's achievement is of a different order. He does what only the very greatest acting does - he opens up the secret places of the human heart, allowing us to glimpse truths about ourselves that we can barely acknowledge, in Vanya's case the overwhelming sense of waste, the impossibility of love, the death of hope. Redgrave knew about such things. As if at destiny's behest, his early life shaped him to experience loss, disappointment, rejection.

He was unique among the great actors of the 20th century in that he was actually born into the theatre. Both parents were actors, as were many of his forebears. His father, Roy, was a feckless charmer of a barnstormer who made his way to Australia, where he triumphed in outback melodramas, occasionally featuring live sheep; his mother Daisy and the infant Michael joined Roy, somewhat against Roy's will, and stayed with him for a little while, during which time the boy made his stage debut, running on at the end of a sentimental monologue to cry "Daddy!" In fact, he couldn't bring himself to utter the word and instead burst into tears, a nice metaphor both for his relationship with his father (from whom they parted shortly after and whom he never saw again) and for the unusual degree of emotion he was to bring to his own work as an actor.

His childhood, back in England, was as unsettled as the life of a single parent who was a jobbing actress on tour could hardly fail to make it, and he was constantly given over to the care of aunts (and "aunts"), frequently depending on the kindness of landladies. Then, quite without warning, his mother married a very respect-able and comfortably-off businessman and their lives changed hugely for the better - in the material sense, at least. Redgrave was plunged into the inevitable Oedipal alienation, in addition to resenting what he felt to be the bourgeois nature of their new life. He was sent to a minor public school where he was blessed with an inspired English teacher who staged plays to a high level of excellence. He also experienced the usual intense crushes on various fellow pupils; before long he had been to bed with men and with women.

Both sexes were understandably smitten by this immensely handsome, elegant, witty and infinitely vulnerable young man. At Cambridge, in the late 1920s, he had long-term love affairs with several men, moved in Bloomsbury circles and was in touch with many of the Apostles; this was the epoch of Burgess (who designed a play for him) and Blunt (with whom he co-edited a magazine). He was confirmed in his leftwing political attitudes, though never formally a Marxist. He was not an especially diligent scholar, but absorbed a very wide culture, particularly during a visit to Heidelberg, which was rare for an actor at the time. He became a schoolmaster, plunging immediately into directing and acting in school productions, playing Hamlet, Lear and Samson Agonistes. By the age of 26 he felt strong enough to enter the fray professionally, playing a vast range of roles in the course of a year at William Armstrong's Liverpool Rep, where he met and married Rachel Kempson. Within a year he had been snapped up by the Old Vic and was playing Orlando opposite Edith Evans's Rosalind, one of the great romantic partnerships of the decade; a year after that he was cast in the leading role in The Lady Vanishes for Alfred Hitchcock, his film debut. Four years into the business he was an established star in both media.

Despite his splendid physical and vocal equipment - the nearest thing to an acteur noble this country has produced - he did not quite fit into a pre-existing mould. "What sort of actor do you want to be, Michael?" Edith Evans had asked him. "Do you want to be like John, or Larry, or Peggy Ashcroft, or me? What sort of standards are you aiming at?" He was in fact that unheard-of phenomenon, an English leading actor who was not an extrovert, always seeking to create from within. Like Charles Laughton, with whom he had surprisingly much in common, he was always in touch with his inner drama, and his best work possesses a sense of fathomless pools of complex life within. Unlike Laughton, his relationship to his own body and his face was not anguished; it is in fact very often the gap between the nobility of his appearance and the turbulence inside which gives his acting its extraordinary tension.

He was desperately needy in his sexual and emotional demands. "I am shallow, selfish (horribly), jealous to a torturing degree, greedy, proud and self-centred," he wrote to John Lehmann; "I have grasped at people's love and done vain and stupid things to get it; I am at times hideously immoral." An example is the passionate affair he had with Edith Evans during and even after the run of As You Like It , starting when Rachel was seven months pregnant with her first child Vanessa, and continuing thereafter for nearly a year, an affair of which Rachel remained ignorant till the publication of Bryan Forbes's biography of her some 40 years later.

Later, the affairs were with men, including at least four long-term relationships, all of which Rachel was told about to the accompaniment of copious tears, and all of which she learned to live with: indeed, she even learnt to live with the lovers themselves. He was so infatuated with Noël Coward during their brief affair that it was with him and not Rachel that he spent his last night before beginning his wartime naval service. She was curiously tolerant, almost unnervingly so. In addition to the marriage and the official lovers were unending one- night or indeed one-afternoon stands, for which purpose he had rented an office off St Martin's Lane, plus pick-ups in parks and stations; later, territory not covered in Strachan's book, he was to go into darker and darker realms sexually, usually fuelled by large quantities of alcohol. These encounters were always accompanied by terrible remorse and vows of renunciation, always broken, sometimes on the very day of the diary entry that records them. This is something that goes well beyond simple bisexuality or mere promiscuity. It is an irresistible compulsion, driven by unshakeable guilt and the constant need for endorsement. It was inextricably bound up with his art. "I like attempting parts of men, as it were, in invisible chains."

The miracle is that for so much of his career, until he was stopped in his tracks by Parkinson's disease shortly after his 60th birthday, he remained so productive and so constantly illuminating in his work; he maintained an elegance and splendour through some of his most demanding roles and despite the unremitting intensity of his private experience. His classical roles - and in one glorious season at Stratford he played King Lear, Shylock and Antony - were absolute reinventions of the characters, but the re-invention was completely unself-conscious: he worked from profound inner promptings, his transformations organic and radical.

As a director, too, he worked with exceptional taste and intelligence; and finally as a writer he produced two of the finest books in the language about acting, and a haunting novel, The Mountebank's Tale , about an actor and his doppelgänger, whose epigraph (by Rilke) seems to tell us something very personal about the enigmatic Redgrave himself: "I can only come to terms with inner cataclysms; a little exterior perishing or surviving is either too hard or too easy for me. In the life of the gods... I understand nothing better than the moment they withdraw themselves; what would be a god without the protecting cloud, can you imagine a god worse for wear?"

Simon Callow's book Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu is published by Vintage.