Science fiction is all around us, from clandestine electronic surveillance to robots taking our jobs, from death-dealing drones in the skies of Pakistan right through to the second industrial revolution unleashed by 3D printing. It's more than a century since writers began charting the technological dream of human civilisation we now live in, but some readers are still put off by a writer who reaches into the future, a novel with a spaceship on the cover.

Like any enduring cultural experiment, science fiction has evolved its own codes, its own logic. Some of the genre's most intense and visionary work talks in a shared language of concepts that can be hard for the uninitiated to penetrate – works Samuel Delaney's Dhalgren or James Tiptree Jr's Ten Thousand Light Years From Home, for instance, would be a forbidding place to start. But if you want to catch up with the literature of our shared future then where can you begin?

It would be hard to find a better starting point than Mary Doria Russell's The Sparrow. Mankind receives a signal from space, music from the alien world Rakhat. The first to respond are not governments or even corporations, but the Jesuit missionary order, who send a private expedition in a hollowed out asteroid to make contact. The novel is told in retrospect through the eyes of the only surviving crew member, priest Emilio Sandoz. If this scenario sounds at all oddball to you, please put those feelings aside. The story of the first encounter between humankind and alien life that Russell creates is both devastating and an awe-inspiring treatise on man's relationship to our universe.

Pattern Recognition by William Gibson is quickly becoming historical fiction. It so astutely pinpointed the emerging trends in technology in 2003 that a decade on from its publication it reads more like a documentary record than a work of SF. Cayce Pollard is a 30-something hipster immersed in the new media world of global corporate brands, who finds herself drawn in to a dangerous conspiracy as she tries to track down a mysterious set of video clips on the internet. Gibson's seventh novel pre-empted the YouTube revolution by mere months, and is still required reading for anyone trying to understand the fractured reality of our media-saturated world today.

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K Le Guin is among the first major works of feminist SF, alongside Marge Piercy's Woman on the Edge of Time and Joanna Russ's The Female Man. I could in fact have included any of Le Guin's novels in this list, but The Left Hand of Darkness arguably marks the point where SF came into its true political strength. Genly Ai is an envoy sent to the planet of Winter to petition for its entry to the Ekumen. But Winter is a world unlike any other, its inhabitants neither male nor female. The construction of identity – of gender, race and class – is at the heart all of today's political and social struggles. Le Guin's genius was to show how SF could be a powerful tool for dissecting and reconstructing those identities.

The Player of Games by Iain M Banks takes at least a little inspiration from the masterworks of Le Guin. The Culture is a galaxy-spanning civilisation that lives in perfect utopia. Nothing amuses the humans and computer Minds who run the Culture more than messing around with less evolved, more barbaric civilisations. Jernau Gergeh is the Culture's greatest game player, dispatched on a mission to the Empire of Azad, a brutal set of distant planets whose political system is structured around the game of Azad itself. The strength of Banks's writing is as much in its wit and bombast as its smart political thinking, but readers will find plenty of big ideas to get their teeth into.

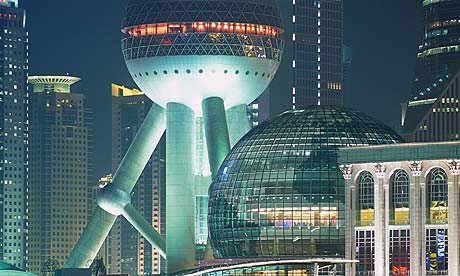

China Mountain Zhang by Maureen F McHugh is perhaps the most mundane of my five picks here. Rafael Zhang is mixed Chinese and Puerto Rican, living in a near future where China has become the political and technological global super-power. Zhang is also gay, a cause of major problems as he tries to advance in a conservative world. The young man's attempts to qualify as an engineer are continually frustrated by a world of social hierarchies, oppressive government and rapacious corporations reaching into the lives of individuals. China Mountain Zhang is a reminder that for all its galaxy-spanning ambition, sometimes SF gives us as accurate description of the present day as anything you can find in the mainstream.