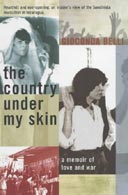

The Country Under My Skin

by Gioconda Belli

380pp, Bloomsbury, £18.99

For many of the journalists who covered the central American wars in the 1980s, Gioconda Belli was the Nicaraguan revolution at its most glamorous and enticing. A beautiful, sexy daughter of the upper middle classes, Belli had rebelled first against convention, by publishing poetry that was frank about female desire, then against the mores of her class by taking a lover while she was married. Finally she rebelled against the 40-year dictatorship of the Somoza clan (it had ruled Nicaragua since 1936) by signing up with the Sandinistas.

It was an irresistible combination. Belli has often written about her body as a metaphor for her country. This memoir describes in frank detail the degree to which she lived that metaphor. At every stage of her journey, there's a new passion. Her husband, married at 19 in her haste for adult life to begin - and with whom she had two daughters - quickly palled and was replaced in her affections, first by a poet who encouraged her to write and introduced her to bohemian Managua, then by a revolutionary who was killed by Somoza's National Guard. Belli's quests for both revolutionary triumph and the ultimately fulfilling love affair ran in tandem until finally the revolution failed and she found lasting happiness - in one of life's wry little jokes - with a US citizen, Charlie Castaldi. Judging from her description of the chauvinism of the Sandinista men, she made a wise choice.

Belli's is a life filled with more drama than most of us could manage over several lifetimes. She survived the devastating earthquake of 1972 that laid waste most of Managua. Before the Sandinista victory, she worked underground, using her day job in an advertising agency as a cover for collecting information and filing reports to the Sandinistas on prominent citizens. She worked as a courier, ferrying money and weapons to and fro. She had to flee into exile, was tried in absentia and sentenced to seven years in jail, then flew back to Managua the day after the fall of the dictatorship bearing the first edition of the new government's newspaper. Dressed in fatigues and army boots, she became a well-known figure in Managua, first running the TV station - a job she abandoned, to her regret, to serve her next but one lover, the legendary guerrilla leader Modesto, who had become minister of works. She toured the Soviet Union and the eastern bloc, she visited Libya, was crudely propositioned by Omar Torrijos, the dictator of Panama, and eyed up by Fidel Castro. When the relationship with Modesto ended she quit to set up a media operation. Finally, when the Sandinistas lost the 1990 election to Violeta Chamorro, Belli left for the US and a new life in Santa Monica.

It would be easy to satirise this account of a naive young woman for whom the passions for revolution and revolutionaries were so hopelessly confused. But Belli in many ways represented that aspect of the Sandinista revolution that attracted the sympathies of many who would not have signed up for the grim existing socialism of the USSR or even Fidel's tropical socialist dictatorship in Cuba. It was not her political sophistication - and certainly not her personal constancy - that made her so attractive. It was her idealism.

Given the choice between the passion for justice of people like Belli, and the greedy and ugly dictatorship the Sandinistas had overthrown, it would have been perverse to pick the dictatorship. The same was true, come the Reagan years, of the choice between the sleazy, CIA-funded Contra operation, with its drug-dealing and deception of the US Congress, its Oliver North and its Otto Reich (now recycled in the Bush administration), and the Sandinista efforts at social justice, soon to be wiped out by the new war with the United States.

Belli's own disillusionment with the Sandinistas, concealed at the time, is also frank in this account. The growing authoritarianism of the Ortega brothers, Humberto and Daniel (later accused by his stepdaughter of sexual abuse), the fact that the core leadership were committed Marxist-Leninists and the recklessness with which they both cultivated the socialist bloc and funnelled arms to the rebels in El Salvador made them an easy target for Ronald Reagan and brought their own revolution down in flames. They could certainly have been wiser. But it would probably have made no difference. They came to power when Jimmy Carter was US president and benefited from Carter's perception that US aid to Nicaragua could keep the Sandinistas out of the Soviet camp. It might have worked, had the next administration shared Carter's vision. But in Reagan they encountered an enemy as ideologically determined as Fidel and one who was not prepared to tolerate either support for El Salvador or anti-Yanqui posturing. Between the two millstones of the cold war, Nicaragua was ground to powder.

Belli's account of these years is personal, emotional and human; revealing, in its way, of life on the inside of the revolution. As such it makes compelling reading. There are, though, some omissions that I find surprising.

Of all the Sandinista inner leadership, Belli seems to retain some sympathy for Tomas Borge, who served as minister of the interior in the Sandinista government, a man she describes as sensitive and kind. Her biggest complaint against him is that Borge tried to end Belli's relationship with her American lover for security reasons.

There is no mention of another, more serious episode that some have laid at Borge's door - the bombing in 1984 of a press conference called by the rebel-turned-maverick-Contra, Eden Pastora, at La Penca in Costa Rica. Three journalists died and more than a dozen were wounded, including a British journalist, Susie Morgan. For years, several of the victims, including Morgan, investigated the outrage, convinced that it was a CIA plot. But in 1989, it was reported that the man who planted the bomb was a former Argentine guerrilla who had been living in Managua, part of a cell that was run out of Tomas Borge's ministry. Borge has always refused to comment.

It is impossible that Belli did not know about La Penca. But if the revelation that it was a Sandinista outrage and not a CIA one shocked her, she does not mention it.

Belli says little of Nicaragua today. Perhaps it is too painful. But despite their many failings, the Sandinistas did hand over power peacefully when they lost the 1990 election. And if some grabbed a few assets as they left, they looted far less than at least one of their successors. After Chamorro came President Arnoldo Aleman, whose personal wealth went up by 900% during his presidency, according to the Nicaraguan comptroller general's office. The poverty of most of the rest of Nicaragua is as shocking as ever. The US got what it wanted, though. When the first McDonald's was opened in the capital, the ceremony was attended by the president and blessed by the cardinal archbishop. Nicaragua had been made safe for democracy.

· Isabel Hilton's most recent book is The Search for the Panchen Lama (Penguin).