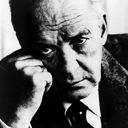

Sales of a dead writer's papers are common enough, but the nachlass of Vladimir Nabokov, auctioned last week by his son Dmitri, was unusual. The entire collection fetched almost £500,000, and among the items attracting the highest prices were the novelist's delicate drawings of butterflies. Most of them are fanciful in name as well as colouring. Nabokov drew them sometimes as doodles, sometimes as a small gift, especially for his wife.

They are prized by collectors not just because Nabokov was a great writer. He was also, by the time he died in 1977, the world's best known lepidopterist. Collecting butterflies was as much a passion as writing. In his wonderful autobiography of a Russian childhood, Speak, Memory, he recalls its birth, at the age of 7. He chased his first papillons on his family's country estate near St Petersburg. When he fled the Nazis for America in 1940 he was stirred most by the thought of all the new butterflies of the new continent. Appropriately, he was to die partly as a consequence of a fall in the Alps while butterfly hunting. His net, he recalled, caught in a tree "like Ovid's lyre".

He did not just collect butterflies, he examined them under the microscope. His favourite haunt was not a library but the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Classification of specimens required painstaking recording of wing markings, it also often involved minute analysis of the male genitalia. He wrote learned papers on the subject ("Nearctic Forms of Lycaeides Hübner") and planned as his magnum opus not a great novel but a complete catalogue of the Butterflies of Europe. Though he worked on it for years, it was too huge to finish.

He belonged to an international community of entomologists, which included gifted amateurs such as himself. They acknowledged him as the greatest expert on the American family of Polyommatini, the so-called "blues" of his adopted country. In his honour, species have been named after him and after characters in his novels (Nabokovia ada, Paralycaeides shade). His collections are in the museums of Harvard and Cornell (he lost three collections moving around Europe).

Aficionados of his fiction (and the odd detractor) might think that Nabokov's vocation was connected to his achievements as a writer. He recalls from childhood the business of killing a specimen with characteristic, discomfiting vividness: "the subsiding spasms of its body; the satisfying crackle produced by the pin penetrating the hard crust of its thorax". Precise, beautiful, unsettling: just like his fiction.