Authors' letters are customarily filed under "non-fiction", but for some their correspondence is just another dimension to the imaginative structures they erect.

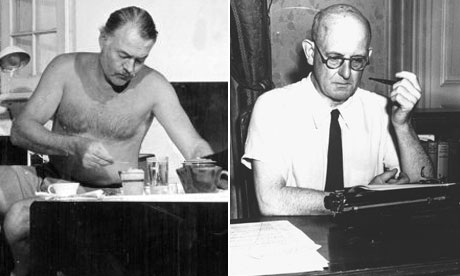

This month sees the publication of Letters by two 20th-century literary greats, PG Wodehouse and Ernest Hemingway. Each, in his own way, had a profound effect on the literary language and imagination of his time. Both were more or less contemporary, Wodehouse (born in 1881) died in 1975. Hemingway, born in 1899, committed suicide in 1961. Both reached the peak of their powers in the 1920s and 30s. So far as I know, they never met, though their paths might have crossed in Paris during the second world war. Neither really enjoyed their postwar creative lives. And as for their letters …

It would be hard to imagine two more contrasting volumes.

Wodehouse was a man who gloried (and perhaps took refuge) in his work. Like many great writers, he was always working at his typewriter. When he wasn't writing short stories or novels, he was corresponding with his agent, co-writers like Guy Bolton and George Gershwin, and old schoolfriends. He often wrote 15, sometimes 30, letters a day. The letters accumulate into an iceberg of self-denial and self-discipline. He is, as I've said, in my biography, the laureate of repression. Many letters are simply repeats of what he's told others before on the same day. As a reader you have the sense that PGW has an eye on posterity (almost all of the letters are typed), or at least on contemporary disclosure. What little he gives away, of a personal nature, is so fleeting and elusive that nothing is really revealed. And yet, put them together in a single volume, as Sophie Ratcliffe has just done for Random House, and an intriguing picture of a great 20th-century writer at work begins to emerge. In its peculiar English way, it has a strange intimacy, the perverse fruit of Wodehouse's instinctive, Jeevesian, discretion.

Hemingway is the polar opposite. His letters were never intended for publication, and they are surprising. The first volume (from 1907-1922), has just been published by CUP as part of a multi-volume project, tidying up behind the previously published Selected Letters. The contrast with Wodehouse's tight-lipped reticence is almost comical. In one letter to F Scott Fitzgerald Hemingway writes "to me, heaven would be a bull ring with me holding two barrera seats and a trout stream... and two lovely houses in the town: one where I would have my wife and children and be monogamous... and the other where I would have my nine beautiful mistresses on nine different floors..."

Behind the hard-living, hard-loving, tough-guy literary persona we find a loyal son pouring his heart out to his family, an infatuated lover, an adoring husband, and a highly committed friend. If Hemingway shares one thing with Wodehouse it's in the discipline he brought to his work. The letters show him making big personal sacrifices to get his stories written.

Sophie Ratcliffe will be introducing the Wodehouse Letters in a Saturday Guardian review essay this weekend. The Hemingway letters are available from the Cambridge University Press. Wodehouse, the humorist, gets one highly commercial volume, put together by an overworked scholar and mother-of-two. Hemingway, the American literary icon, will get many volumes, organised by a fearsome team of American editors. As Wodehouse himself once observed, humorists never get taken seriously by the lit crit intelligentsia. In 2011 these two great writers, who signed themselves either "Plum" or "PG" , and "Bongy", "Oinbones", "Old Brute", "Stein/Steen" and "Wemedge", are still making headlines and selling books.