On the 21st floor of a building near Central Park, New York, a corridor of closed doors and discreet nameplates leads to that literary holy of holies, the Wylie Agency. Known in the book trade as “the Jackal” on account of his business tactics, Andrew Wylie’s clients include the gilded living such as Martin Amis, Dave Eggers and Milan Kundera, and the illustrious dead, among them Mailer, Updike, Bellow.

When the electronic latch clicks open for admission, the atmosphere inside is so hushed I whisper my intention – an appointment with their most refulgent star of all: Salman Rushdie. The receptionist whispers back, in a manner that suggests I may have got the time, date, place or perhaps even the person, wrong “Salman?… You mean Salman Rushdie?” No one stirs or shows any interest. Another day, another interview to publicise another new book. In this silent laboratory where literature and commerce collide, the work continues.

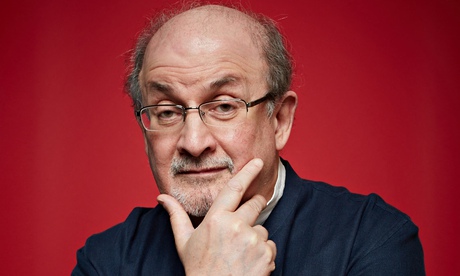

Within moments Salman Rushdie, equally punctual, arrives and breaks the spell. He is affable and warm in greeting, hot in person – this is Manhattan in midsummer. His striped linen shirt, cotton trousers, white socks and trainers manage to avoid any hint of fashion except of the engagingly crumpled variety. We have met before, in a distant past in London when Rushdie was still living under the Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa (prompted by Rushdie’s 1988 novel The Satanic Verses), with no known address, bodyguards at his side, forced to travel in armoured cars. For the past 15 years he has lived in New York. His 12th novel, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, will be published round the world in the English language this week.

Set in the near future after a storm strikes New York City, Two Years features a gravity-defying gardener called Geronimo, and Dunia, princess of the jinn. These pre-Islamic folklore creatures, the novel tells us, “are not noted for their family lives (But they do have sex. They have it all the time.)”. They tend to be amoral, sneaky, lustful, power-hungry and irreligious. Rushdie adds his own chuckling rubric: “We humans have everything else, but not endless sex. Even endless sex after a couple of millennia probably gets a little tedious.” He has trawled a sea of Indian and Arabian wonder tales for this novel, such as The Arabian Nights and the Panchatantra, hauling all of it into a baroque and barnacled fantasy narrative. “The source material is a great storehouse of tales I grew up with, that made me fall in love with reading. I thought this is the literary baggage I’ve carried around all my life and now I’m putting my bags down. Let’s see what happens when I unpack them and those stories escape into this place.”

At fewer than 300 pages and having taken three years to write, it is one of Rushdie’s shorter books. It traverses the world of the 12th-century philosopher Ibn Rushd (Averroes), spanning New York and Fairyland, with walk-on parts for Isaac Newton, Henry Ford, Mother Teresa and Harry Potter. “Yes they’re all there to be squeezed in,” Rushdie says, as if in explanation. “It might be the funniest of my novels. I have to say that even Andrew Wylie when he was reading it said he was laughing out loud, and that’s not easy to achieve.”

The zigzagging between literature, religion, fantasy, the mock-academic and the bawdily demotic will be familiar to any reader, or failed reader, of Midnight’s Children. This is Rushdie’s stylistic thumbprint. Chosen from Two Years at random, the following is representative:

This means that you, like all the descendants of Ibn Rushd, Muslim, Christian, atheist or Jew, are also partly of the jinn. The jinni part, being far more powerful than the human part, is very strong in you all, and that is what made it possible for you to survive the otherness in there; for you are Other too.

“Vow,” he cried, reeling. “It isn’t bad enough being a brown dude in America, you’re telling me I’m half fucking goblin as well.”

Despite its subject matter, Two Years is surprisingly benign. “Yes, it’s almost a series of love stories,” Rushdie agrees, a softness in his always well-modulated voice. “I thought it would be so easy, given the news every day, to make a despotic fantasy in which everything is terrible, then it gets worse and ends horribly. That’s exactly why it isn’t interesting to do that. So what should I do instead? I had the idea that there might be a future which is a lot better than we currently have any right to expect.”

The book’s epitaph is Goya’s engraving The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters from the series Los Caprichos. “The novel is, I think, about reason and unreason. You can’t simply say rational is good and irrational bad. One aspect of unreason is imagination and dream. When reason and fantasy are combined, they produce wonders. When separated they create monsters. I think many people feel these days that the familiar rules of the world seem not to apply any more.”

Is he referring to a loss of courtesy and decency, or to security, war, technology? “I mean the way we think things are. We all have our own understanding of what the world is and how it works. And suddenly a whole range of things have happened – what Grace Paley called enormous changes at the last minute – partly technological, partly political, the end of the cold war, the rise of religious extremism, the transformation of the world by electronic communication. Suddenly a lot of people, I think, feel a little at a loss.”

“I think” is a common Rushdie interjection. In speech, as in print, his sentences are fluent, looped with brackets and sub-clauses, driven by a sense of narrative and history. “I thought, how would one dramatise a world in which the rules no longer applied? I decided to start with some rather fundamental rules: like gravity. It’s not interesting when people just float off into the sky. What is interesting is when they are just half an inch off the ground. Actually Mr Geronimo the gardener was the first thing I had. But this man whose love is the earth becomes detached from the earth. That was the comedy, and the poignancy. I didn’t even know if he’d come down again, actually.”

One of Rushdie’s lifelong influences is Gabriel García Márquez, author of One Hundred Years of Solitude, the novel so closely identified with magic realism. “The problem with that phrase,” Rushdie cautions, “is that people only ever hear the word magic. The point is that it is a way of trying to combine the fantastic and the realistic into a single narrative.” This technique can be irritating, I suggest. There’s always a get-out clause: the hero can escape from cataclysm by, say, turning into a sparrow and flying off. “The point of any kind of imagined world is that is has to be coherent in its own terms,” Rushdie retorts. “It must not just be whimsical. If anything can happen, then nothing matters.”

His last book was the 600-page memoir Joseph Anton – the title was Rushdie’s alias in hiding. As well as the fatwa, he describes his cosmopolitan Indian middle-class childhood, one boy, born in 1947, with three sisters, and the shock of his arrival in England in 1961 to board at Rugby (an early awakening was the graffito scrawled on a school wall “Wogs go home”.) His love for his two sons, Zafar (born 1979) and Milan (1997), shines through, and the remorse of his failed marriages to their mothers, the late Clarissa Luard, and Elizabeth West, is almost unbearable to read. Wives two and four, the writer Marianne Wiggins and the model and TV host Padma Lakshmi, are given short shrift. He tries hard to describe how, in each case, love and affection turned sour. Both women still come off badly.

Spending several years finding ways of telling the truth “as clearly and accurately as he could” wore him out. “I think what happened is that after I’d finished writing the memoir, I kind of got sick of telling the truth. I thought, It’s time to make something up. I had this real emotional swing towards the other end of the spectrum, towards high fabulism. I had so much enjoyed writing the books for my sons, Haroun and the Sea of Stories and Luka and the Fire of Life, that I thought about that source material again, not for children but for grownups.”

Despite the impact of the fatwa, Rushdie is still drawn – in this new novel too – to the twin dangers of religion and faith. He has said, bluntly, that in the end religion itself will make people sick of God. Does he believe this? “Well I hope so. Maybe that’s slightly optimistic. The number of terrible things being done in the name of religion might be piling up. At some point it might occur to people that the problem lay in the idea of religion. Look, I’m fairly open about not being religious, to say the least, but in the book it’s a conflict because that’s one point of view. The other is also there, which is that people will increasingly turn towards religion.”

This move towards faith, everywhere you turn, still puzzles him. “If you’re a child of the 1960s, one thing that never occurred to us was that religion would become powerful again. It seemed like a busted flush. It’s not that people didn’t believe in various gods, but the idea that this would come to orchestrate the public discourse would have seemed impossible. If someone had said that to me in 1968 I would probably have laughed.”

Rushdie’s experience of living under a death threat has led to an implicit expectation that somehow he has all the answers. As Martin Amis once said: “Salman had disappeared into the world of block caps. He had vanished into the front page.”

“I’d rather be back in the books section,” says Rushdie. “I’m stuck with it. It feels a bit like a millstone because I’ve got other stuff to talk about. On the other hand, the question of religious fanaticism has become so central to all of us we all have to think about it. At least I can do my best to use the experience I have had to try to respond as an artist.” He perceives the Islamic revival as “a narrative of power which can confront overweening western power, and make otherwise very powerless individuals feel as if they’ve got some power. And then it really helps if you are a psychopath and feel like cutting people’s heads off.”

He dislikes the word Islamophobia. The question of extremism does not inhere in any particular religion or any one part of the world. The issues are wider and deeper: “It seems to me that if I don’t like your ideas, it must be OK for me to say so. If you think the world is flat, you have the right to say so and I have the right to say you’re a fool. If you believe in God, and I don’t, it must be legitimate for me to say your belief is full of crap. Why do we have to put religious belief in cotton wool? The point about ideas is that they should engage with each other, not be ring-fenced. It’s a quite different matter to say that there should not be racial prejudice against people. Of course there shouldn’t be. The colour of skin is a fact. Religious belief is an opinion. It seems to me quite legitimate to have counter-opinions to any opinion without being called a name.”

One of the most striking things in the past 25 years, he has noticed, is the cheapening of the value of individual human life, “which certainly a humanist tradition would value very highly. Individual life has become, for many people, disposable. Either you believe in this life, or you think this is just some unimportant preamble to real life, so the sooner we get to the next thing, the better. Unfortunately that’s all nonsense. So a lot of people are in the service of nonsense. Now what is true is that in various parts of Europe there has grown up a kind of extreme rightwing racism that has attacked Muslim communities around Europe, and clearly that has to be addressed as quickly as possible.

“But to protect people’s lives, and their ability to lead them, doesn’t mean you have to refrain from criticising their ideas. We’ve got confused about that. For a lot of people, including these folk who were criticising Charlie Hebdo, questioning ideas was seen as improper, given the depressed condition economically of the Muslim community, as if you’re sort of attacking people who are already vulnerable. That was the argument. I don’t think it holds up.”

The decision of 26 authors to sign a letter in protest against a PEN freedom of expression award for Charlie Hebdo, following the decision of six to withdraw from PEN’s annual gala in New York in April, has left a wound that remains fresh for Rushdie. “I wasn’t by any means the only person on this side of the fence. I think a lot of people felt upset. I talked to Ian McEwan and he felt very shocked and alarmed. It seemed shocking to me that many of these wonderful writers were objecting – Junot Diaz, Peter Carey, Joyce Carol Oates, Michael Ondaatje and more. I would never in a million years have thought they would have been on that side of the argument and it was a shock. We’ve all been friends for 30 years. There’s no question that this has left a bad feeling.”

The lack of understanding, or curiosity, distressed him most. One signatory had not even seen a copy of the French magazine. “We are all asked to sign things all the time. In my view you do not sign anything unless you are absolutely convinced you can stand up and justify that signature. I just thought how awful to vilify the dead unfairly. At least if you are going to attack the dead, who can’t answer back, get your facts right. These people were killed for drawing pictures for goodness sake.”

Unexpectedly he has some enthusiasm for Pope Francis. “I am quite encouraged by the pope right now. He has some progressive ideas. Not entirely – for example the Vatican was horrified by the Irish vote on gay rights and marriage equality. But he seems like quite an improvement on that other one. The person I now call ex-Benedict…”

Rushdie worries about a new doctrinaire Hinduism developing in India, embodied especially in the far-right Shiv Sena party. “I don’t think it would be fair to say that the BJP [Bharatiya Janata party] is as extreme as that but it is becoming more strident and less tolerant in its demands.”

The American Christian right is a force closer to home. “Their problem is that they can’t find anyone extreme enough to vote for. George W Bush wasn’t extreme enough. They voted for him but then they thought he was a terrible disappointment. As he was to so many of us for different reasons [chuckles].” Rushdie adds ruefully: “It’s very interesting to me that [his friend, the late] Christopher Hitchens became popular in a way he never had been before when he started articulating a position against God. I always thought that God rescued Christopher from the American right, because of course they didn’t like it that he was atheist. I do think God is responsible for a lot of trouble. It’s become almost unnecessary to say so.”

In other respects America has been a time of redemption and reunion. Many of his oldest friends now live in New York, including Martin Amis and the poet-journalist James Fenton. “Ian [McEwan] is the one who hasn’t done it. He’s so rooted to England. Martin’s here, though oddly I don’t see that much of him – sadly. But most of my friends here are not transplants.” No one in New York can say “wogs go home” as everyone “comes from somewhere else”. As Rushdie said so pertinently in his memoir, “Migration tore up all the traditional roots of the self”.

Of New York he observes: “The very rich immigrant texture of this city is something I find endlessly fascinating. And by the way, it has created a rich new wave of American literature. We all know American literature owed a lot to European culture, to Italian, to eastern European Jewish migration and so on. But now suddenly there are these new immigrant stories arriving from everywhere: Bengali, Vietnamese, Chinese, Afghan, from the Dominican Republic and so on and so on.” Writers he mentions include Jhumpa Lahiri, Nam Le, Yiyun Li and Khaled Hosseini.

He has never forgotten the Indian-born publisher Sonny Mehta (editor-in-chief of Alfred A Knopf) telling him, after Mehta’s move from London to New York in 1987: “For people like you and me, Salman, it’s a really good idea to leave the British empire.” At the time, Rushdie says, “we just thought it was a joke. I still think it’s mostly a joke. But it’s true that this country left the British empire too. I don’t feel particularly alienated from England. Most of my closest family are still there. It’s just that here I found a place that I like living. Square peg finds square hole.”

He thrives on the energy of a city that hardly sleeps. “If you call the New Yorker office at 8.30am, everyone’s in. And if you call back at 8pm, they’re there.” Is that such a good thing? “Yeah, I like that it’s such a hard-working environment because it makes it easy to work. You feel an idiot if you’re not.” He works an ordinary office day, rarely breaking for lunch. “I’m not a 5am person. I think Martin gets up much earlier than me – or he used to work till lunchtime then go off and play tennis. I don’t know whether he still does. Maybe for all of us our sporting days are fading into the past…” He laughs. Rushdie himself was no mean ping-pong player during his enforced exile, making secret arrangements to play in safe houses of friends.

According to the UK gossip columns, you would think Rushdie’s only sport now is attending parties with one or more luscious women. “That’s such crap. Really, when, where are these parties? Give me some examples? I’m quite a gregarious person. But a writer’s life is a writer’s life. You spend most of your time alone in a room. If you don’t, books don’t get written. As it happens, I’ve written a lot of books, which means I must have spent a certain amount of time alone in a room… You know it never used to be like that. I think it was entirely because when I first came to New York I became involved with an extremely beautiful woman and that’s when all this started. There’s nothing much I could do about it. That’s what happened. I was extremely fortunate.”

He and Padma Lakshmi divorced in 2007. Press prurience – in his memoir, he watched Lakshmi “pose and pirouette” for the paparazzi – is the one topic that provokes any hint of ire. “I don’t have a wild life. I don’t go out more than anyone else does. The difference is that whenever I go out someone takes my picture and puts it in the Daily Mail. It’s pathetic. Writer goes out in the evening. So what? People can do whatever the hell they want.”

A keen tweeter, Rushdie has 1.06 million followers on Twitter (self-description: “In the immortal words of Popeye the Sailor Man: I yam what I yam and that’s all that I yam.” Why? He likes Popeye.) Nor has he any illusions about its value. “What worries me most is the anonymity thing, the trolls. It allows people to be fantastically discourteous in a way they never would be if their real name was attached. But you know, when you have a book coming out, it’s not unhelpful to have a million people to talk to, and the million people have been self-selecting in that they are interested in what you have to say. So that’s a way of talking to them directly instead of, say, going through…”

A journalist?

“A journalist! Twitter gives you a megaphone. It’s not just about ‘here’s my new book, please buy it’.”

No, really?

“No! But if there’s something you want to say, you can do it straight away. I’m ready to block people. They can be abusive once but not twice.”

Some of his tweets are extremely funny. One, from a student in Nepal, said: “Dear Sir, with due respect our college teacher told us you have african [sic] girlfriend younger than you?” Rushdie, now 68, replied: “Nonsense. My girlfriend is from Antarctica and is much older than I am. I hope that helps.”

A new liaison?

“There isn’t a new liaison.”

Can I say that?

“Of course you can say that. It doesn’t mean there isn’t going to be. But really. Is this what they talk about in English lessons?

Without brackets or full stops, he laughs long and hard and disappears into the hushed corridor to go in search of the Jackal.

Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights is published by Random House on 8 September, £18.99. Click here to order it for £15.19