When I started writing this column three-and-a-half years ago, the digital publishing revolution was just starting to filter down to public consciousness.

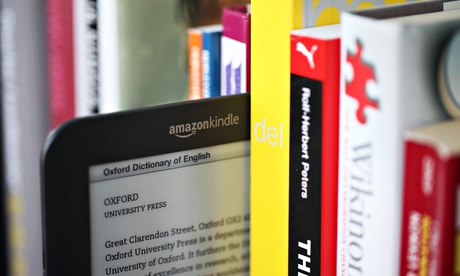

From a pub lunch where someone was showing off their new Kindle to the 8.53am slot on the Today programme, conversations revolved around the same old questions. Is Amazon intent on destroying literary civilisation or is it a well-oiled customer-focused machine? Are publishers greedy and conservative middlemen or gatekeepers upholding quality? Is the person opposite you on the train reading Middlemarch or self-published vampire porn? What happens if you drop your e-reader in the bath?

The answers tended to be very black and white. You were either an ebook zealot or a luddite refusenik. A heartless free-marketeer or a romantic economic illiterate. There was little room for nuance or ambiguity.

As the market matured, people realised it was possible for screens and print, and good high street bookshops and internet retailers, and self- and “mainstream” publishing, to coexist (sort of) happily, after all. This spirit of collaboration is already resulting in more exciting literature – take Iain Pears’s Arcadia (Faber/Touchpress), a rule-breaking, non-linear novel conceived as an app, but also available in hardback.

More serious questions about the book industry now have space to be aired. Are we publishing too many books? Why are the authors whose books make it into bookshops overwhelmingly white and middle-class? Is there a crisis of mediocrity in nonfiction? Is the hardback/paperback cycle outmoded? For intelligent discussion of some of these issues, listen to the podcast of the Front Row debate from this year’s Hay festival.

Has the e versus p debate been a distraction? Yes, but a useful one. It has made readers more clued up about how books are made – and more aware of the power they have to influence what and how they read.