I’ve got a secret vice. I love to visit rare book rooms and leaf through the pages of 16th-century traveller’s tales or 15th-century editions of Petrarch with their brilliantly coloured pictures. Once, I even found a design by Botticelli in a religious tract in the British Library.

This is not actually as criminal or difficult as it sounds. I was researching a book at the time and all the yellow-leafed volumes whose pictures I pored over in the rare books room at St Pancras were more or less relevant to it. Anyone with a British Library pass can do the same. But it raises the question of what great libraries are for: is the research they make possible just for PhD students assembling demographic data on medieval Norfolk or should the rich, aesthetic delights of illuminated manuscripts, 18th-century caricatures and scientific illustrations be available for us all to enjoy as art?

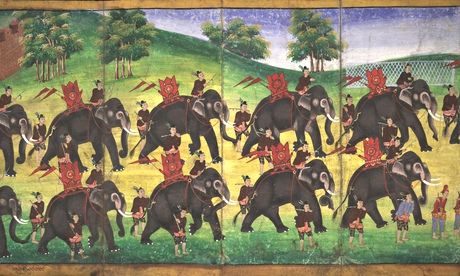

One way libraries are opening their secret worlds to everyone is by putting some of their most curious or majestic items online. Oxford’s Bodleian, one of Europe’s greatest and oldest libraries, is the latest to do so with digital.bodleian giving users unprecedented opportunities to browse precious volumes and their wondrous illustrations from our armchairs, if anyone still has armchairs, or cafe stool or even in a punt (it’s Oxford after all).

You can do all the online things people love to do online, from assembling your own collection of favourites to taking a selfie with Cicero (except the latter), but the most intriguing aspect of this and other digital rarity collections is that it changes the nature of research. Instead of an arduous activity undertaken by determined scholars, visiting the digital Bodleian is a pleasant browse through the virtual past that all of us can undertake. It is like something out of a story by the librarian and fabulist Jorge Luis Borges in which all the great books and philosophies of the world have become one walk-through art gallery, their strange languages fusing into brilliant illuminations. That is to say, this way of consulting a library replaces reading with seeing.

I am never going to learn Hebrew now but it’s entrancing to look at venerable Jewish books in the Bodleian virtual library. It is equally beguiling to come across a manuscript of plays by the Roman writer Terence that was copied in the 12th century. I can’t make much sense of the archaic script but the pictures are amazing – they include a page of Roman theatrical masks, as imagined by a medieval monk. This book preserves a dialogue between the sexually promiscuous pagan comedies of antiquity and the Christian scribes who kept them for posterity; just to think about this manuscript’s miraculous existence is to imagine a story more dramatic than Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose.

Is it a decline of western civilisation if libraries pass from monastic secrecy to democratic openness and books become pleasures for the eye? I’d be hypocritical to say so since as I have confessed I use actual physical libraries in the same way the digital library demands to be used – for the sheer visual fascination of the book as an object and storehouse of images. A society that sees is not necessarily worse than one that reads. Illumination may contain more wisdom than obscurity. Libraries are not simply embracing the digital age but glorying its new culture of the book as a marvel, a wonder, a magical object.

I just hope there is no digital analogy for one of the greatest writers about libraries, MR James. This Oxbridge scholar’s ghost stories tend to start with library researchers coming across grey-faced cobweb covered librarians or curses written in old books. Just watch out for pop-up runes among the digital incunabula.