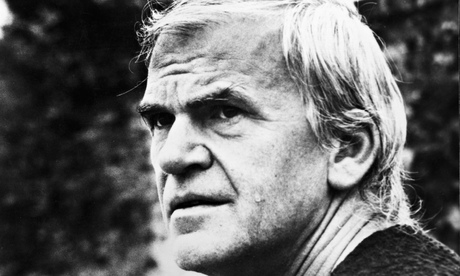

Milan Kundera was a gateway drug for me, my initiation into the world of serious literature. I still have the heavily (and embarrassingly) annotated edition of The Unbearable Lightness of Being that I was given by Giles H, a portly and bespectacled boy in the upper sixth when I, a pimply fourth former, was dabbling in the callow delights of Salinger and Kerouac. Kundera seemed more vital, more political, more potent, raunchier. I took to walking around with the book sticking out of my blazer pocket, putting a Czech diacritic over the “s” in my surname. The Book of Laughter and Forgetting merely confirmed me as a Kundera man: the fragmentation, the melancholy, the politics (“our only immortality is in the police files” is heavily underlined in my copy), and, again, the sex (the scene in which Eva masturbates to a Bach suite while Karel looks on retains its piquancy).

I read the early, highly political Czech novels next, which seemed like stretching exercises for his masterpieces, but still full of wit and verve and wonderfully quotable bons mots (I had taken to smoking Gitanes and wearing black turtlenecks by this point). I was a little underwhelmed by Immortality (1990), but had then caught up with him, if you like, and awaited the publication of his first novel in French with impatience (Kundera moved to France in 1975 and started writing in French after Immortality). The slim novel that came, Slowness (1995), was a disappointing meditation on perspective and modernity wrapped within a series of barely overlapping half-narratives. Reading his subsequent novels – Identity (1998) and Ignorance (2000) – became an increasingly laboured process of digging out the occasional gems from the abstraction and tub-thumping philosophising. When he moved into French it felt like he stopped writing novels and started writing loosely threaded pensées – some of them highly entertaining, but rarely building into anything more than a parade of clever aperçus.

I approached his first novel in 15 years, The Festival of Insignificance, all of a flutter. There is always the hope that a writer you love might produce a late flourish – Roth’s Nemesis is, I think, one of his finest novels (and came after The Humbling); Bellow went off the boil and then produced Ravelstein; Alice Munro’s best collection so far, Dear Life, was published when she was 81. Kundera has just turned 86. The Festival of Insignificance takes to new extremes the process of distancing and abstraction that has typified his French output. It is only 128 pages long, but shows so little interest in providing the reader with reasons to continue turning the pages that the reading process becomes a pitched battle between hope and boredom, with the latter crushingly victorious.

At this point, when addressing the work of a writer one has admired who has produced a stinker, it is usual for the reviewer to spend as much time as possible summarising the plot. So little does The Festival of Insignificance deal in the traditional satisfactions of the novel that it becomes difficult to render even this courtesy. An old man hosts a party to which four friends are invited – two as guests, two as caterers; a woman (who we later discover is one of the friends’ mothers) tries to drown herself, then murders her rescuer; Stalin tells obscurely significant stories until his incontinent stooge Kalinin wets himself. The book is a celebration of the unimportant and superfluous (thus it centres on Kalinin, not Stalin) and every time we are promised a passage that is momentous or meaningful, we are tugged back to the insignificance of the title. It is possible to be interesting about boredom – Lee Rourke’s The Canal managed it, The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa did it brilliantly. Here Kundera mirrors the drabness of his subject matter in flat, affectless prose. It makes for a novel that promises little and delivers less.

One of the four friends in the book, Ramon, laments the ageing process, which has seen him diminish from a lothario with a “passion for dazzling others; for startling them by an amusing remark; for conquering women before their very eyes” into one of “the dismal army of the retired: his nonconformist remarks, which had used to keep him young, now… made him an uncontemporary character, a person not of our time, and thus old”. Kundera’s novel feels stranded like Ramon, lacking political or artistic urgency, taken up with struggles in arenas of literary theory whose suns have long set. The occasional ham-fisted flourishes of authorial interjection fall horribly flat (one of the characters explains his knowledge of Hegel by saying “our master who invented us once made me study him”). The problem is, I think, that there are a host of authors who read and loved Kundera about the time I did, then used him as a launchpad into dazzling new novelistic worlds (here I’m thinking Adam Thirlwell, Laurent Binet, Scarlett Thomas, Siri Hustvedt). While their work thrums with life and ideas, Kundera’s recent(ish) output feels like a series of retreats into mere cleverness.

Reading The Festival of Insignificance made me wish for the vim of those great middle-period novels (which, admittedly, seem a little more adolescent and posturing on rereading some 20 years later). It also made me think about what causes novelists to lose their edge. If, as Malcolm Gladwell claims, genius is all about the hours you put in, why is it that so many authors burn brightly in their youth then fizzle out? I think it’s partly that writers as they age appear to become increasingly interested in style to the exclusion of other aspects of the novel. Children can tell stories, they seem to say, what is important is the form, the shape of individual sentences. This can lead to flashes of brilliance, but more often it is ossifying, stultifying, and leaches life from the prose. Flaubert’s mother said to him once “Your mania for sentences has dried up your heart.”

It also strikes me – and I realise that any number of exceptions can be found to these generalisations – that writing over the longue durée tends to be about refinement rather than accretion, so that novelists try to distil their themes into ever more crystalline and purified forms, to extract the essential and discard the excesses of their early years. This refinement can turn up the occasional Nemesis-like jewel, but more often it leads to a Hadji Murat or a Doctor Fischer of Geneva – desiccated, joyless, insignificant.

The Festival of Insignificance is published by Faber (£14.99). Click here to buy it for £11.99