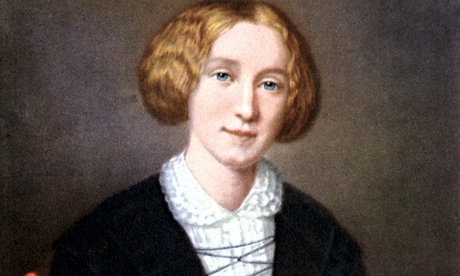

“For there is, in great writing, a sinister power, primitive and overwhelming, whose grasp upon the organs within us unsettles and disturbs.” The nameless narrator of Patricia Duncker’s sixth novel is talking specifically here, towards the end of the book, about the writing of George Eliot, “the Sybil” of the title. Sophie and the Sybil is in part about the relationship between a writer and her readers; not merely the several obsessive readers (both real and fictional) who cross paths with Eliot in the course of Duncker’s historical narrative, but the ambiguity of the author’s own feelings towards her. “[T]he grain of resentment one writer always feels for another whom she hails as ‘Master’ – and I use that word advisedly – would not dissolve,” Duncker explains in her afterword, in which she also explains the multi-layered structure of the book, “a Victorian comedy of manners which had, as all comedy must do, a darker and more sinister set of shadows at the edge”.

The historical part of the story concerns the final years of Eliot’s life, beginning in 1872 when she was travelling in Germany to escape the censure of English society over her liaison with her married lover, George Lewes. Her German publisher, Wolfgang Duncker (no relation, but a happy coincidence that sparked the idea for the book), charges his feckless younger brother Max with accompanying her to the spa town of Homburg for the purpose of securing the rights to Middlemarch. Also staying in Homburg is 18-year-old Countess Sophie von Hahn, wilful and beautiful, promised in marriage to Max and herself an ardent admirer of the Sybil. The stage is set for a three-way relationship that mirrors “the sexual triangle of Middlemarch”.

Sophie pours out her heart to the Sybil in a letter, but her devotion turns to resentment when she is spurned, her anger fuelled further by her suspicion that, despite the narrator’s emphasis on the Sybil’s age and ugliness, Max has somehow fallen under her spell, and later by the discovery that she has used her as the model for the character of Gwendolen Harleth in Daniel Deronda. This hatred simmers over several years and is finally vented in an explosive confrontation in which Duncker’s portrayal of Eliot is deeply moving – one of the few moments where she allows the reader full emotional engagement with her characters. For this book is deliberately tricksy, playing with and challenging our assumptions about the form of the novel, its authorial voice and the characters it represents. “I have mixed fiction with the detail of real lives in outrageous ways,” Duncker declares gleefully in the afterword, but we already knew that from the novel’s epigraphs, one of which is a knowing quote from the novel’s fictional narrator commenting on what she perceives to be the intentions of the author who created her.

This narrator pauses the action throughout the book to comment on it directly to the reader like a Greek chorus, albeit one versed in contemporary literary theory. These asides, full of diverting historical and literary background, nonetheless have the deliberate effect of distancing the reader from the story’s characters, ensuring that we observe them in an artificial light, as if through a proscenium.

This is not the first time Duncker has explored the often obsessive and possessive relationship that can develop between a writer and his or her readers; in this regard it most closely resembles her acclaimed 1996 debut, Hallucinating Foucault. Sophie and the Sybil digs deeper into the same theme, with intriguing arguments, but though often highly entertaining, ultimately it remains a novel that engages the intellect rather than the emotions.

To order Sophie and the Sybil for £12.74 click here