Like the great 19th-century novelists, the neurologist Oliver Sacks has crystallised different ways of being human for our medicalised times. His chosen literary mode is not the novel, but the clinical tale, a form inherited from the case histories of Freud and the Russian neuropsychologist Alexander Luria.

George Eliot’s Dorothea, the young, middle-class woman who thinks she can buy into the world of ideas by marriage, may not be for Sacks. Instead he gives us Miss R, a chronically ill and institutionalised sufferer of the 1920s epidemic of sleeping sickness, who is woken from her frozen Parkinsonian state by the ambiguous miracle of a druggy L-DOPA kiss – and a doctor.

His heroes are not Balzac’s provincials on the make in the glittering capital of corruption, but autistic boys with a genius for drawing or prime numbers; or a man afflicted by the tics and uncontrollable swearing of Tourette syndrome; or Dr P, a distinguished musician who has lost the ability to recognise faces but sees them where they are not.

For all their lacks and losses, or what the medics call “deficits”, Sacks’s subjects have a capacious 19th-century humanity. No mere objects of hasty clinical notes, or articles in professional journals, his “patients” are transformed by his interest, sympathetic gaze and ability to convey optimism in tragedy into grand characters who can transcend their conditions. They emerge as the very types of our neuroscientific age.

The fascination of Sacks writing about his own life is to discover what contributed to his affinity for those who are constituted eccentrically. In his brilliant memoir, Uncle Tungsten, he focused on his early boyhood, his medical family, and the chemical passions that fostered his love of science.

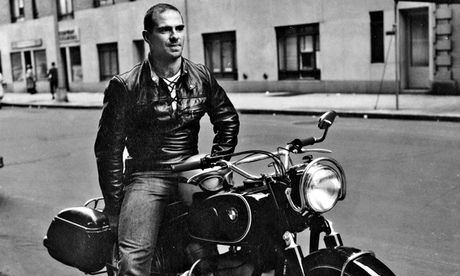

On the Move begins where that left off. A youthful, leather-and-jean-clad Sacks astride a large motorbike, bearing a distinct resemblance to Marlon Brando, is poised to take off on its cover. The book comes in tandem with Sacks’s moving statement in the New York Times in February about the imminence of his death. In this genial and often humorously narrated life, he is very much alive and full of passionate energy, as well as of and wry self-awareness.

Sent away from London and the warmth of family life during wartime bombing, Sacks endured the horrors of bullying at boarding school. Feeling “imprisoned and powerless”, he developed a passion for movement – for horses, skiing, and motorbikes. He got his first bike when he was 18. The speed and freedom of the road attracted him. So, too, did the romantic classlessness of biker society in those hierarchical 50s.

The growing torment of his schizophrenic brother, the drugs that sometimes calmed but as often tortured the ailing youth, left a deep mark on Sacks and, of course, his devastated parents. The seeds of Sacks’s later affinity with patients undoubtedly in part lies here.

When it becomes clear that Sacks will be among the last cohort conscripted into national service, he leaves home, first for Canada and then to become an intern in California. These early years in the US of the 60s are marked by a form of escape which doubles as a form of perceptual self-experimentation: drug-taking. Sacks becomes addicted to amphetamines – an “empty ecstasy”. Only when he moves to New York and starts work at a migraine clinic does the concerted action of a friend and the beginning of a long-term analysis wean him off.

Sacks may be odd and an enthusiast, but he is a writer of tact. He doesn’t speculate on what part his mother’s anguished statement on learning of his homosexuality – “I wish you had never been born”– played in his life. He writes of a few love affairs, his road trips, and obsessional body building, but doesn’t explain why, after one affair, he gave up sex for some 35 years. He is less reticent about the professional differences that marred some of his early endeavours, and his attempts to marry the neurological with the psychiatric, as well as medicine with its own history.

“Sacks will go far, if he doesn’t go too far,” a schoolmaster had noted about the 12-year-old Oliver. A restless energy and rebelliousness are undoubtedly what allowed Sacks to break the mould of the reductive scientising that characterised the American medical and neurological establishment he found himself in and to see the humanity in damaged patients. The last is what has made him a saintly figure for many.

But this is also a writer’s life. Early friendships with Auden, Thom Gunn and his contemporary Jonathan Miller loom in importance, as do the literary example of Luria, his relations with the publisher of Awakenings, and the actor who played him in the film, Robin Williams. Called Inky from boyhood on, Sacks had nearly 1,000 journals and more letters and clinical notes to feed this autobiography. He is an astute observer of the life around him. Judging from early motorcycle diaries and writings included here, he could have had an alternative career on the road with Hunter S Thompson. We are all in his debt for taking up the case history.

Lisa Appignanesi’s latest book is Trials of Passion (Virago/Little Brown). To order On the Move go to picador.com/books/on-the-move