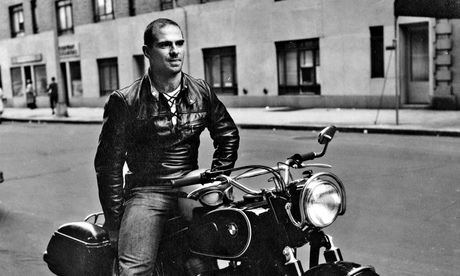

Critics rushed to pay tribute to the eminent neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks, who is ill with terminal cancer. But while some managed to stay focused on Sacks’ groundbreaking work on the human brain, others were momentarily distracted by the photographs accompanying his latest memoir, On the Move, which featured the dashing young doctor sporting a leather jacket, and a notably skimpy pair of Speedos. “May I just pause to say of the young Dr Sacks: well, phwoar!” enthused Janice Turner in the Times. “Forget the off-duty Santa of later years. At 25, Oliver was a Brando of the brain in motorbike leathers, known by his middle name Wolf.” All the more baffling, therefore, that he remained celibate for 35 years – although on the upside, it provided Turner with the irresistible opportunity for wordplay: “While Sacks in the sack is a disaster, in the cerebral plane he soars.” The celibacy question also preoccupied James McConnachie, who noted in the Sunday Times that he “offers regret but no real explanation” for it. “You feel, by the end, that you still do not quite know him and even, astonishingly, that he still does not quite know himself.”

Reviewers were divided as to whether Kate Atkinson’s A God in Ruins was a worthy follow-up to her critical and commercial hit Life After Life. In the Telegraph, James Walton saw it as “triumphant”, “a wholehearted and perhaps even rather subversive celebration of such resolutely unfashionable qualities as choosing duty over self-fulfilment and emotional restraint over causing distress to others”. For Amber Pearson, in the Daily Mail, however, it was a “quieter, more restrained work”, and the Sunday Times’s Theo Tait found that “it suffers by comparison with Life After Life in that there are no narrative pyrotechnics to distract from Atkinson’s weaknesses. She has a tendency, for instance, to reproduce the events of the war using tired historical shorthand.” In the Observer, Stephanie Merritt warned against underestimating the book. “Though it may appear to lack the bold formal conceit that made Life After Life so original, don’t make the mistake of thinking that Atkinson has abandoned her interest in authorial playfulness.”

Another big-hitter, Toni Morrison, was also given a mixed critical reception for her latest novel, God Help the Child. The book “offers only the most inconsequential answers to questions of grave consequence”, wrote Sarah Churchwell in the Spectator, comparing it to “a colouring book that no one bothered to colour in”. Peter Kemp in the Sunday Times was also unconvinced. “Unsurpassed at portraying racial and cultural trauma among America’s blacks, [Morrison] operates with far less sureness when exploring childhood injury ... God Help the Child is an ill-judged deviation from imaginative territory where she is supreme.” Bernardine Evaristo went the other way in the Observer, writing that Morrison “proves with God Help the Child that her writing is still as fresh, adventurous and vigorous as ever”, and noting that “characteristically deft temporal shifts and precisely honed language deliver literary riches galore”. In the Daily Telegraph, Leo Robson occupied the centre ground: “The slender novel that Morrison has constructed ... proves intricate, inventive and stinging – but also, none too surprisingly, overcrowded, heavy-handed, tiring.”