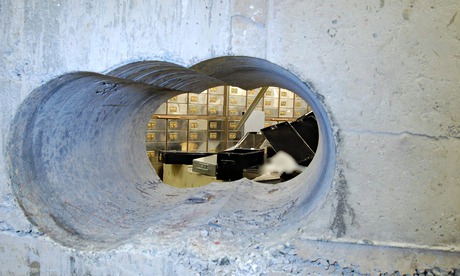

It’s time to call Sherlock. A picture of the hole drilled by ingenious thieves through the 50cm-thick reinforced concrete wall of the basement vault of Hatton Garden Safe Deposit over the Easter weekend reveals a mystery well beyond the powers of Scotland Yard. Inspector Lestrade and his men admit they are currently trying to understand how nine thieves got through a space just 25cm high and 45cm across.

Elementary, my dear Watson. Plainly this was a crime with something of the bizarre about it. Scotland Yard should perhaps be looking for a criminal who is also an employee of the Zoological Society of London. The thief sent through the hole was plainly not human. It was a trained monkey or small ape, or even – I refer you to the case of The Speckled Band – a snake.

Depressingly, modern security methods make Sherlock’s speculations unlikely. From CCTV footage the police know that human beings did get through that hole into the vault. Unless they were chimpanzees disguised as men. Perhaps – suggests Holmes – we are looking for a team of acrobats, trained to wriggle through apparently impossible apertures. Were any circuses in the vicinity of Hatton Garden at Easter? There, I believe, you will find your contortionists.

Some crimes tickle everyone’s fictional fancy. The Hatton Garden heist has all the makings of a crime classic. No one was physically hurt, so there is no guilt about enjoying this robbery as entertainment (we’ll get on to the loss of property in a moment). It is also genuinely mysterious. The image of the slender space through which the criminals apparently squeezed only adds to the daring of their entry into the basement by abseiling down a liftshaft, and to their good luck that an alarm was ignored and they were able to spend two consecutive nights rifling through safe deposite boxes at their leisure.

Many people inevitably see this as a real-life version of heist movies like Ocean’s Eleven, Ocean’s Twelve and so forth. Personally, I find heist films really boring. I’d much rather see Hatton Garden as a locked-room mystery in the tradition of Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Allan Poe. In one of the very first crime stories, written in 1841, Poe’s Parisian detective Auguste Dupin proves that a hideous double murder in an apparently secure upstairs room was in fact carried out by an orangutan. Now we’re talking. To repeat the advert placed in a newspaper by Dupin – has anyone lost an orangutan? Or perhaps, given the size of the hole, a pmeerkat.

But wait. Looking through this mysterious hole into the mayhem of the looted vault, are we not forgetting the victims of crime? It is all very well to indulge in whatever crime fictions you enjoy – from Poe to Goodfellas (“It was the greatest heist in Holborn’s history ...”) – but surely we should be more horrified by this crime against property.

Uh-huh.

There is something missing from this image of a pierced wall and a pilfered fortune. It is empathy. Most people find it easier to identify with the criminals – to imagine them as witty desperadoes led by George Clooney – than to feel for the wealthy folk who left valuables at Hatton Garden. Behind our armchair detective fun lies a sense that no real harm was done here, except against the rich.

It is the same emotion of our time that is making it so hard for the Conservative party to establish a solid lead in the election despite a run of good economic news and dire warnings by business against a Labour/SNP government. Because we hate the rich. The financial crisis has left a real and justified sense of inequality and the scandal of runaway financial capitalism across the world; in Britain it makes it hard, perhaps impossible, for the Conservatives to convince enough people they are running the economy for the many rather than the few. And that same outrage at unfettered wealth turns the Hatton Garden robbers, whoever they are, into perverse folk heroes.

It is not just a hole in a wall. It is a window on to a glittering secret world of wealth. The metallic deposit boxes literally shine, in a brilliant array of what looks like silver and gold. It is like peering into the tomb of a pharaoh. So that’s what the inner sanctums of modern money look like – deathly and silent reserves of mysteriously obtained wealth. Where there are opulent tombs, you will always get tomb raiders.