The writer and activist Larry Kramer lives at the foot of Fifth Avenue in New York, in an apartment overlooking Washington Square Park. For the entirety of our conversation the sound of a saxophone, playing a jazz riff, drifts up from below. Sometimes it’s louder than Kramer’s own voice, which is hoarse from a series of illnesses.

The careful way he sits down shows just how frail he is, but his words still have the strength of conviction, if not volume. For example: when I ask him about the historians who told the New York Times that they had been surprised to find themselves mentioned (and criticised) in his new, ribald and quite unforgettable book, The American People: Volume One, he grins and says: “Tough shit.”

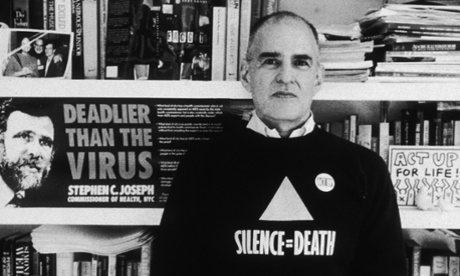

Kramer is more used to argument than your average man. Now 79, he came of age in an era when being gay was still illegal, when that counterculture wasn’t just rebellious but in serious peril. He was a firsthand witness to the deadly costs of that taboo, because when Aids came and swept the city, it took a long time to get American health authorities to pay attention. He was there, in the front row, to catalogue and object to every moment of that neglect as a founder of Act-Up, the organisation behind the protests that drove American health authorities to take Aids seriously. In fact, he still worries they didn’t go far enough. “There are 80 million people who have been infected [with HIV],” he told me. “When I first read about it, there were 41.” (The joint United Nations program on HIV/Aids puts the figure at closer to 34 million by 2014.)

There is, indeed, a dark abyss between those numbers. It can be hard to think about for very long, the scale of it too horrible to keep in sight. But Kramer has spent his whole life staring at it. And that has marked him, though in the wider culture it has mostly marked him as a very angry man. A 2002 New Yorker profile of Kramer, by the writer Michael Specter, is stuffed with examples of people calling Kramer a fringe element. Specter wrote that when he first met Kramer, he himself thought Kramer was “a complete lunatic”.

Specter changed his mind, though. And throughout the reports over the years are mentions of Kramer being soft-spoken in person. Ellen Barkin once told a New York Times columnist she found him a “paradox” because in spite of flashes of temper, he could be “the sweetest man she ever met”.

The firebrand reputation – the metaphors used are always incendiary – has clearly come to bother Kramer, a bit. He complains to me that every article about him begins with some statement about what a “loudmouth” he is. But he wants to be considered an artist too: “I like to think I work very hard on my writing. And unfortunately in this country you can’t be taken seriously as an artist if you’re also an activist.” This, he says, is in contrast to South America or France, where artists “write political stuff and it’s fine! It doesn’t matter … That’s sort of very provincial about America.”

He is certainly not the only American artist who has made that complaint in recent years. Strident politics are out of fashion. And The American People: Volume 1, certainly wears Kramer’s politics on its sleeve.

The book is being marketed by the publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, as a novel. But, as Kramer will readily tell you, he doesn’t consider it fiction, not precisely; everyone in the book is “based on a real person”. These people have various occupations and preoccupations, but they are unified by the author’s animating purpose, which, Kramer says, is “to write a history of my American people”.

His people are gay, and they have mostly been ignored by conventional history. The book’s animating idea is spoken by Kramer’s own stand-in in the book: “If Fred’s history will seem less unbiased than some would wish, let it never be overlooked that it is no small task to record a history of hate when one is among the hated.”

“Most histories are written by straight people who wouldn’t know, see the signs that a gay person does when they look at a person’s life,” Kramer said. “I mean, how could you write the life of Mark Twain without realising that he was hugely, hugely gay? The way he lived, who his friends were, and how his relationships began. And what he wrote about! I don’t know how you could avoid the assumption that he’s gay.” (Kramer is not the first to raise this possibility, but it is not a view accepted by most Twain scholars.)

Other prominent historical figures are also re-imagined (or re-stated) as gay. There are other writers, like Melville, whose gayness is obvious to Kramer. There are also presidents who he feels clearly were: Lincoln, for starters, and of course George Washington himself. Kramer weaves these addresses of history with long passages about sex, for which, he tells me, “I kept trying to expand my horizon of dirty words. Which you might say, after awhile that becomes a task in itself.” Kramer says he’s always been enchanted with language: he cites Evelyn Waugh, or Trollope or Forster or Raymond Chandler.

What makes the book compelling is the engine of passion that fires it. It is certainly an aggressive work, but the sheer force of its argumentation can grow on you. At 800 pages it certainly requires some kind of force to carry the reader along. Kramer wanted specifically to write a long book because, “I had written plays, I’d written novels, I’d written endless political speeches, screenplays, I wanted to try and stretch myself in terms of form.” He admits that he discovered that “it’s not as easy as you think.” A second volume is planned.

So far, reviews of The American People: Volume 1 have been middling, and when I saw Kramer he had already been annoyed by the review he’d received in the New York Times. In it, the staff critic Dwight Garner likened the book’s sprawl to that of Thackeray or Thomas Pynchon’s work. But then he delivers a sort of death blow: “As a work of sustained passion, it is formidable. As a work of art, it is very modest indeed.”

Kramer is rather used to bad reviews of his work. “The Normal Heart got terrible reviews when it came out. I’ve never had a good review in the New York Times.” Over the years Kramer has often excoriated the Times for being slow to cover the Aids crisis, so much so that the newspaper is practically a character in The Normal Heart, the autobiographical play about the beginning of the Aids crisis that made Kramer a hero. It was put up at the Public Theater in New York by the legendary producer Joe Papp in 1985, and more recently was made into a very successful HBO movie.

The endurance of The Normal Heart suggests that Kramer’s work is rarely best judged by its initial reception. Frank Rich, who was the Times’s theatre critic in 1985, sniffed that Kramer lacked “theatrical talent”. He also added: “Some of the author’s specific accusations are questionable, and, needless to say, we often hear only one side of inflammatory debates.”

It is now “needless to say” that the Aids crisis turned out to be much more than an “inflammatory debate”. It was, instead, a catastrophe. The incendiary anger it provoked came from the desperation of people who saw a system that was failing them. Failing to keep them alive, that is.

To a large extent Kramer still feels it’s failing. “I’m trying now to raise the whole issue about cure! Why is it taking so long? It’s the 35th year of a plague. That’s a long time. We should know more. And have more.” It would help others and perhaps serve his own fragile health, too. Kramer, who was diagnosed with HIV in 1988, begins to tell me about his “long and involved relationship” with Dr Anthony Fauci, a public health official who was often the target of his tirades.

Now, Kramer says, “I both love him and hate him. he gave me medicines that helped me live … they helped me when I had my liver transplant. I’m always screaming at him that they’re not working fast enough, and they’re taking for ever, and is no one in charge, you know? This is a mammoth Manhattan project that is needed.” And as he talks his hoarse voice at last gets louder, as passionate on this subject now as he has ever been.