In 1995, I’d just begun my freelance working life as an illustrator. I switched on the internet twice a day. International clients would still get in touch by landline, or maybe they’d fax. I didn’t use email for personal correspondence. There was no social media. It was several lifetimes ago.

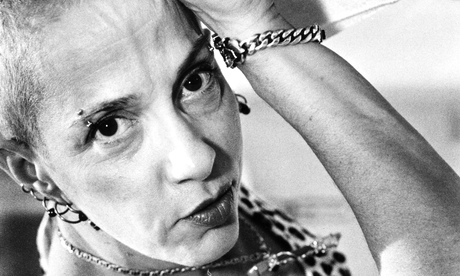

In 1995, Kathy Acker – writer, artist, punk icon, best known for her transgressive, experimental novel Blood and Guts in High School – emailed cultural theorist McKenzie Wark, or rather he emailed her as she flew back to the US from Australia after their brief sexual and intellectual encounter. And she wrote back.

“Perhaps email does best with crushes,” suggests the writer artist and critic Matias Viegener, who is also Acker’s literary executor, in his introduction to Acker and Wark’s collected correspondence, written over a few intense weeks and now published as I’m Very Into You. The book, he suggests, is “not an artefact of an affair, but of a seduction,” bookended by the protagonists’ meetings IRL in Sydney and New York. Seduction via email in 1995 was similar to the moment when, as Philip Larkin had it, “sexual intercourse began/ in nineteen sixty-three …/ Between the end of the Chatterley ban/ And the Beatles’ first LP.” It created not so much a new erotic act as a separate erogenous zone, one – as Acker says in her second email – of “pure narcissism”, the opposite of meatspace sex, which Wark describes as “centralising in space and localising in time”.

Wark and Acker’s emails criss-cross, often aimed not at, but past each other, as they try on sexual, political, and national identities in the freefall of the virtual world, with all the insecurity and performativity we selfie-snappers take for granted. Acker is always “flipping” – “flipping out” as well as “flipping” or “switching” sexual preference and gender identity. “Oooo this is like writing!” squeals Acker, whose best-known works question both identity and authority, rewriting books ranging from pulp fiction to canon classics to star versions of the author.

A self-confessed “style sponge”, her emails are an exhilarating stream-of-consciousness, a paragraph-less, almost sentence-less, flow: “My mind,” she says, “does not go in any linear fashion whatsoever”. Wark matches Acker’s intensity and range as they discuss everything from Elvis to Deleuze, Bataille to The Simpsons, but his writing is comparatively sedate. “Slipping between straight/gay,” he writes, “is child’s play compared to slipping between writer/teacher/influence-peddler whatever.” If Acker performs some of the possibilities of the internet, he unwinds and analyses them. Wark untangles Acker’s emails, sometimes sorting his responses into numbered paragraphs: “just when I think I’ve abstracted something from [your writing], found a diagram for you, you reach out from the page and tear it all up.” “I’m not being grammatical,” writes Acker, who already understands that “such are the delights of email”.

“It can’t be mistaken to need someone else to love, and yet only human solitariness allows human survival,” Acker wrote in her version of Don Quixote. The internet seems to offer the chance to square this circle, providing what Acker calls “a privacy based on our not knowing each other long,” but when the emails do hit home emotionally, around plans for a real-life meeting, the correspondence turns interestingly uncomfortable. ”I’m not fucking playing games,” writes Acker, trying to pin Wark down on what he wants from their relationship. Wark apologises for “my cavalier use of the medium”, and admits “I’m a bit stuck for what to say next”. “Life doesn’t exist inside language,” as Acker said on her spoken-word album, Redoing Childhood, then, as though signing off an email that offers the hope of communication even as it denies the possibility, “Too bad for me - Kathy.”

There might seem something odd about publishing a book of emails – a technological step backwards into paper-based linear narrative – but this mashup of media is analogous to, as well as essential commentary on, Acker’s literary cut-ups: her extraordinary texts in which the generic fights with the intensely personal, so that they seem all depth and all surface, simultaneously literature and criticism. An interdisciplinary artist whose life was bound up with her work, and whose image was both her identity and her brand, Acker might have seemed made for the internet age (as Wark claimed in a recent interview, she’d already been thrown out of several proto-chatrooms).

“Acker understands that writing without myth is nothing,” wrote the American author and film-maker Chris Kraus, who is currently working on a critical biography of Acker. In this collection, the focus can’t help but be on Acker, already a literary star. But Acker died of cancer in 1997, and never saw Facebook, or YouTube: she never encountered trolling, or emoticons, Grindr or the Dark Net. Wark went on to write A Hacker Manifesto and Gamer Theory; his Twitter avatar, like the book of emails, was until recently another artefact of their relationship: the ring Acker gave him, which is also pictured on the cover of the book.