There’s a beautiful moment in Terry Pratchett’s Bromeliad trilogy. A colony of tiny Amazonian frogs has lived inside a tree-top flower for generations. The flower is their world. Until the day one of them climbs up, peeps out and glimpses the unimagined vastness of the forest canopy, with its galaxies of flowers like his own. It’s a parable about the history of science, but it’s also a great image of Pratchett’s own creativity.

Discworld began – in the The Colour of Magic – as a comprehensive parody of fantasy. Its “hero” Rincewind is a rubbish wizard whose mother “ran away before he was born”. The action takes place in Ankh-Morpork – a city that feels like the unsanitary shanty town that might have grown up around Gondor if Middle Earth had had an industrial revolution.

But like the frog, Pratchett kept seeing more in the world he had created. He found that he could use it to satirise not just fantasy, but also cinema, the police, financial institutions, the politics of fear, military adventurism and, the ultimate absurdity, our own mortality. Whereas Tolkien spent years imagining the geography, history and languages of Middle Earth before releasing his books, Discworld grew in front of our eyes and tumbled off into streams – Death, The Witches, The Watch.

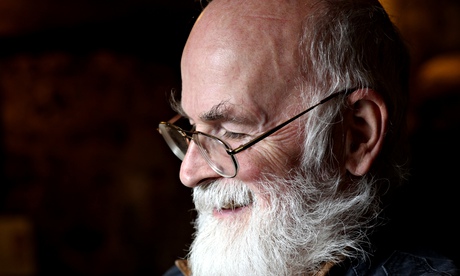

It was the fans who drew the maps and genealogies. Pratchett seemed to be exploring the place and, because it was such a revealing mirror, exploring us, too. He sometimes wore a T-shirt with the slogan: “Tolkien’s dead, J K Rowling said no, Philip Pullman couldn’t come. Hi, I’m Terry Pratchett.” But his invention was different from theirs. He wasn’t imagining an alternative universe; he was reimagining ours. His fantasies sit alongside – and are the equals of – those of Rabelais, Voltaire, Swift, Kurt Vonnegut and Douglas Adams. He’s surely our most quotable writer after Shakespeare and Wilde. Granny Weatherwax’s definition of sin – “When you treat people as things” – is all you need to know about ethics.

So there will be many commentators today bemoaning his lack of literary prestige, but the fact that he dodged the gongs is part of his power. Whereas all my beloved P G Wodehouses and Philip Pullmans are neatly arranged on the bookshelves, my Pratchetts are strewn under the beds, in the bathrooms, the glove compartments. They have shopping lists, takeaway orders and Scrabble scores scribbled on the fly leaves. They were part of life.

You could take a random Discworld to the dentist’s knowing that you could open it at any page and be transported. A writer with mere literary prestige would not have inspired my 11-year-old to create a Lego tombstone for him. Rincewind is always looking for something “better than magic”. Pratchett found something better than literature.

We live in a society whose culture is driven by fear of death. We adore youth. We pay for science that extends life rather than enriches it. In his life and in his work, Death – “not cruel, just terribly terribly good at his job” – was the final and finest target of Pratchett’s satire. In Mort – Pratchett’s most popular novel – Death takes on an apprentice so he can have some time to himself. As he learns to appreciate life, so the apprentice comes to appreciate Death.

I hope in all the pages that will be written about him in the next few days, it will be remembered that he was a great, Carnegie-winning children’s writer.

For me, his masterpiece is that Bromeliad trilogy. The story of a group of nomes who live in a big department store and who have taken its slogan “Everything Under One Roof” to mean that there is nothing at all outside the store. They worship an inanimate box called “The Thing”, which they belief will lead them “home”, a ridiculous belief that turns out to be true.

This twist is at the heart of Pratchett. In an age of fundamentalisms, he embraced doubt, the possibility that a stupid belief might have something going for it, whereas an obvious and rational truth might get you nowhere. I hope that that is the twist he is enjoying today – that having dismissed all hope of an afterlife, he is sitting on a cloud with Jonathan Swift and Swift is saying: “By Jesus, Terry, I wish I’d written Truckers.”