The illustrator Fritz Wegner, who has died aged 90, was a prolific creator of funny, detailed and memorable drawings, and a much-loved teacher. Born in Vienna to secular Jewish parents, Michael and Eti, he had a secure childhood, but it was abruptly ended by the Anschluss of 1938. After drawing a cartoon of Hitler and enraging his pro-Nazi teacher, he understood the danger he was in, and his parents organised his departure, alone, by train to London.

His parents and sister were able to join him later, but initially Fritz was taken in by George Mansell, one of his teachers at St Martin’s School of Art (now Central Saint Martins), and his wife. As Wegner recalled in an interview: “It was an extremely generous thing to do and indeed I lived with them for several years, learning everything I later knew about lettering, penmanship, gilding and the Roman alphabet. That was the start of an early passion, after which I moved on to doing illustrations.

“George, an extremely knowledgable and cultivated man, was able to teach me a great deal more about life. He was responsible for giving me my first formal education in cultural matters, and introducing me to literature, the English language and a love for the arts. He had an immense influence on my life and I was very grateful to him.”

At the outbreak of war, Wegner worked as a labourer on the land in Buckinghamshire, gaining further education from his co-workers, mostly conscientious objectors. While there, he met the journalist Janet Barber, who was living in a nearby village. They were married two years later and moved to Bromley, then Hampstead Heath.

Wegner began his long career as a freelance illustrator by working for Liliput magazine and drawing book jackets. Titles included the English edition of The Catcher in the Rye (1951), and religious works by Dorothy L Sayers such as The Story of Noah’s Ark (1956) and The Days of Christ’s Coming (1960). Working constantly to support a family of three, Wegner undertook a range of illustration work, including stamps for Christmas and other festivities and, from 1973, a string of drawings for the American children’s magazine Cricket, which featured running commentary by insect characters. He found his metier in children’s books, including the new edition by Bodley Head of André Maurois’s Fattypuffs and Thinifers (1968), subsequently reissued with colour added.

Wegner’s illustrations are nearly always comical, and, while crowded with detail, the strength of the drawing and composition draws the eye inwards to explore their parallel world. In 1990, he was voted the Illustrator’s Illustrator, although many of his contemporaries became more immediately recognised names. In a tribute for Wegner’s 90th birthday, the author and fellow illustrator Ian Beck wrote, “No one to touch him; wit, warmth, and above all such fine and fluid draughtsmanship,” while for Shirley Hughes, “Looking at the range of his delightful picture books, you see not just a stunning technique but a true artist whose first priority is to serve the story and make it come alive for the reader.” Wegner declared his love for “fanciful stories that give me lots of opportunities for invention and humour because those are things I like to bring to my work. It’s not the cartoony, belly-laugh type of humour, but something perhaps a little more subtle.”

One such book was The Wicked Tricks of Till Owlyglass (1989), the German classic Till Eulenspiegel, familiar from Wegner’s childhood, retold by Michael Rosen and published by Walker Books. The same publisher also undertook Wegner’s ambitious project Heaven on Earth (1992), an illustrated summary of the collected lore of the zodiac, with texts distilled from much research by his close companion of many years, Emma Curzon. This was a movable book, with subtle paper engineering: for each of the signs a spread was filled with wit and invention.

For Allan Ahlberg he illustrated Please Mrs Butler (1984), The Better Brown Stories (1996) and The Little Cat Baby (2004), and for Leon Garfield The Strange Affair of Adelaide Harris (1971) and Guilt and Gingerbread (1984).

Wegner was a visiting lecturer at St Martin’s for 25 years from 1969, gently encouraging his students and on one occasion following a tearful beginner under a table to persuade her to come out again. The illustrator Phillida Gili has told how “Fritz gave me the first words of encouragement I ever received at art school.” Other students included Glynn Boyd Harte, Nicola Bayley and George Hardie, who shared his creative love of the past and brought a light but sophisticated touch to their work in the 1970s.

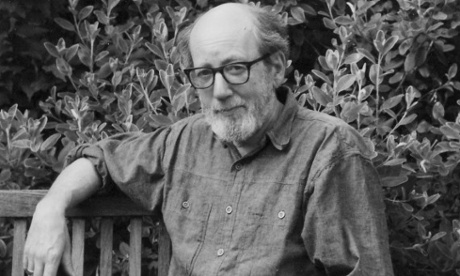

Although Wegner could be modest and diffident about his work, he was a gregarious man, and his domed head and neatly bearded and bespectacled face, with a bow tie for formal occasions, were often seen at the Art Workers’ Guild (to which he was introduced by Mansell in 1952), at the Chelsea Arts Club and at the dinners of the Double Crown Club. The Double Crown was responsible for publishing a pamphlet, Fritzschrift, for his 90th birthday, which should prompt a wider appreciation.

In his final years, failing eyesight and health confined Wegner to home. He is survived by Janet, their children, Nicholas, Charles and Elizabeth, and nine grandchildren.

• James Fritz Wegner, illustrator, born 15 September 1924; died 15 March 2015