Much has been made recently about the over-representation of the wealthy and privileged in the creative industries. I am not sure all this fuss is justified. Certainly the middle and upper class dominate the arts as they dominate all areas of society; that’s why they’re called middle and upper. However, working- (“lower-”?) class writers, actors and filmmakers – sometimes even telling stories from a working class point of view – still pop up regularly in most forms of cultural representation.

The reality of the presence of people from “ordinary” backgrounds in the creative industries is self-evident. There are a few TV writers (Sally Wainwright, Paul Abbott, Jimmy McGovern), filmmakers (Andrea Arnold, Steve McQueen, Ken Loach) and playwrights (David Eldridge, Dennis Kelly, Laura Wade). Certainly there is no shortage of actors and visual artists from non-posh and even underprivileged backgrounds.

But there is one significant area of the arts where inequality is blindingly obvious. It is rarely noted, however, because it has been so true for so long that nobody bothers to remark on it any more. This is visible in the death not only of the English working-class novel but of the English working-class literary novelist. I use the delineation “English” advisedly: the same is not true of Scotland, which from Ali Smith to Irvine Welsh to AL Kennedy and James Kelman boasts a rich stock of authors from the estates, slums and benighted small towns, despite the fact that Scotland’s population is tiny, relative to England.

It is too late to hold a funeral – the passing came around the mid-1960s. But it is important to acknowledge that a significant mouthpiece of a sizeable part of society has been comprehensively silenced, in this field at least, for a generation, probably two.

It is easy to think of working-class novelists and novels, even though the most celebrated are half a century in the past now. The works of John Braine, Alan Sillitoe, Stan Barstow and David Storey come to mind. There are working-class novelists from that and the next generation who are still productive – Melvyn Bragg, Howard Jacobson, Jeanette Winterson, Margaret Forster. But since that brief dawning, working-class writers and working-class narratives have more or less disappeared from the world of literary fiction in England.

All the above narratives – and writers, incidentally – are northern. It is as if the working class south of Manchester does not exist in literary terms, despite London and the south-east containing some of the worst areas of deprivation in Europe. Here I must declare an interest, since I have written two novels set among the southern working class, White City Blue and Rumours of a Hurricane, and one memoir of working-class life, The Scent of Dried Roses. However, I cannot be relied upon to keep the flame alive. I am no longer working class, and even though my next novel has as a protagonist the son of a shoe shop worker living on a council estate, that fact is not central to the narrative. I have little idea what life in the poorer parts of England is like any more, other than what I can glean from documentaries such as Benefits Street.

More recent narratives of working-class life have been published – but only incidentally so. Because stories of “the streets” now tend to come from post-colonial voices, such as Zadie Smith, Courttia Newland, Andrea Levy, Monica Ali and Hanif Kureishi. Their narratives explore multiple identities – ethnic, religious, cultural. These explorations may include class identity, but it is unlikely to be a primary concern.

The politics of identity has replaced the politics of class. Thus “working-class” writing has come to mean little more than “white” writing. Perhaps this is one of the reasons for its fading from view. Because if “working-class” writing is “white” writing, perhaps we are making some kind of a dubious statement in seeking it out, either as publishers or consumers.

This doesn’t, however, answer the question of why working-class writers have been so much less successful in fiction than in other artistic fields, when the literature of the commonplace is still so alive in Scotland (other than Jackie Kay, incidentally, writers from ethnic minorities are in short supply north of the border).

A number of factors are possible to isolate: the slow death of library culture; the fading of books themselves as a dominant cultural form as the internet and long-form TV drama take over; the end of grammar schools, perhaps – all the successful working-class novelists I can think of, including myself, escaped from their culturally impoverished circumstances through grammars (along with playwrights like Harold Pinter, Steven Berkoff, Dennis Potter and Alan Bennett).

Fiction writing, after all, is a “high” literary form (probably the same reason there aren’t many working-class classical musicians). It requires eloquence and education. Neither are particularly prioritised, and may even be stigmatic, in working-class culture (I was often sneered at for having “swallowed a dictionary”). To embark upon a novel requires the belief that its achievement is within the realm of imaginative possibility. Most people from a modern sink estate would find it as hard to envisage pitching for a publishing contract as they would to contemplate applying to be a high court judge.

Its withering as a form also has to do with the de-exotification of the working class. Nell Dunn, upper-class author of narratives such as Up the Junction, wrote about the working class because she found them more “alive” then the people in her own world. From Jimmy Porter to Joe Lampton to Arthur Seaton, in the 1960s working-class characters – mainly but not entirely men – were sexual, instinctive, angry and passionate in the way that their genteel middle-class counterparts were not.

Perhaps, like theatre in the 50s, we have once again become too wedded to politeness (now in the guise of political sensitivity and inner thought policing) and too wary of passion, honesty and, sometimes, vulgarity. The working-class voice now makes the middle-class reader nervous – partly because of guilt, and partly because, as Ken Loach observed, “any working-class person who speak intelligently is absolutely abhorrent to critics.”

From being heroic, interesting, passionate, honest and authentic, working-class people are now seen as white, racist, thuggish, scrounging, loud, unpleasant and uncultured. Are they really like this? I don’t know. That’s the point. There are no writers out there any more to bring us bulletins from the lives of what is probably the largest single group in society.

Ironically, one of our most brilliant and successful novelists, Hilary Mantel, is the daughter of a mill worker. After labouring as a writer for years, how has she finally made her breakthrough success? With a story of the court of Henry VIII and the machinations the ruling classes.

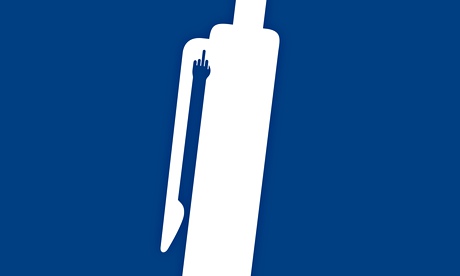

Perhaps there is only one way now for working-class writers to make it: to stop being working-class and, even more importantly, to stop having the bad manners to write about it. Then, if you are able to pass yourself off with the right accent, regurgitate the dictionary you swallowed and keep your horny hands confined within borrowed velvet gloves, then you’re in with a (very remote) chance.