In the introduction to her book on the women of Bletchley Park, The Bletchley Girls, broadcaster Tessa Dunlop, perhaps unwisely, quotes the response of her elderly aunt Sally on the news that Dunlop was to embark on the project: “Gosh, darling … I should think that quite enough has been written on the subject!”

Undeterred, an author in search of an angle, Dunlop pounced upon a description of life at Bletchley by one of her interviewees: “I had no idea how boring it was going to be. It was excessively boring.” This may or may not be a revelation but Dunlop believes that there is an image of Bletchley that needs correcting. “Numerous personal testimonies in the last 40 years have helped bolster the glamorous ‘Bletchley brand’, which now boasts not only a vast museum, but also several television series and films and countless books. Was there anyone left to counter the prevailing opinion?”

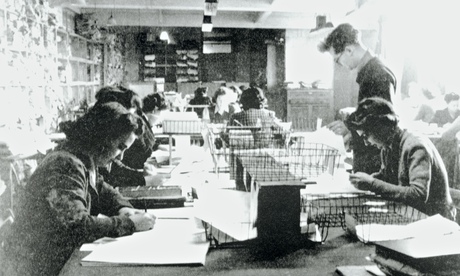

For most of the women at Bletchley, the work was indeed grindingly dull and monotonous and made more so by their having no idea to what purpose they were collating information. Ann Mitchell cycled 10 miles to her night-shift every day, sustained by a cup of Oxo and a boiled egg. In 1944, the sick rate at Bletchley was more than 4%: the monotony of her work (“If you can call it a job, ticking boxes”) drove Jean Fforde to the brink of a nervous breakdown. “I would get up every morning with dread. It went on and on, ticking, ticking.”

Dunlop has interviewed some of those Bletchley women still alive and draws on one or two unpublished diaries. These have yielded some good stuff, especially on the particular intensity of wartime sexual relationships: Alan Turing’s homosexuality was common knowledge among the girls, she was told, and regarded with sympathy: “B[letchley]P[ark] was avant garde and I was young and picked up on the feeling among people that this was perfectly normal.”

Yet Dunlop’s tone jars. There is too much of her and not enough of her interviewees. She cannot resist inserting her own sometimes patronising embellishments: one woman has an “impish grin”, another “a coquettish giggle”; of a third, “even at the age of 11, little Betty was a realist”.

Dunlop is also obsessed by class – in the manner of one treading uneasily in the foreign territory of a past where she believes people thought of nothing else. It is true that Bletchley was marked by a degree of class difference, as was the world outside it. Billets in Woburn Abbey, for example, were snapped up by the posher girls and the rest had to make do with local lodgings.

Yet Dunlop’s flat-footed attention to social pecking orders obscures the broader wartime achievement that saw women of all backgrounds working together – at Bletchley too (as Dunlop’s interviewees, when they are given space, make clear). And she is as excited by a title as a 1930s dowager: I lost count of the times that Jean Fforde is introduced with some breathless reference to her ducal forbears.

The unfortunate title of Michael Smith’s The Debs of Bletchley Park suggests that he might be veering down the same alleyway. Thankfully, however, debs do not dominate (or not unless they have something interesting to say about their war, which they often do) in his brisk and readable story of the women of Bletchley. Women were recruited from a wide range of backgrounds: a lot of the work was drudgery but a certain kind of intelligence was required – language skills, clerical skills, mathematics. Mair Thomas, for example, was a student at Cardiff University, studying languages, when a strange man tapped her on the shoulder in the library and told her to write to the Foreign Office and say that he’d sent her.

Smith, a former defence correspondent and author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park, is good on what the women actually did, what daily operations entailed. Here’s Eileen Plowman on the cracking of the day’s code: “It got more intense once it was broken. They used to say they were ‘breaking the day’. We would set the machines up and then all the messages – there were lots and lots of messages – came through and everybody went mad with all the decoding and it all came out in German. Where I came in useful was that I knew German, because it was all positions of the U-boats and we had to get that right and send up to Admiralty. The next thing you’d hear was that a U-boat had been sunk.”

Dunlop’s aunt Sally is surely mistaken: there is always more to find out about Bletchley. But publishers might give the interesting, intelligent, independent female veterans of Bletchley their proper due and ban the use of “girls” or “debs” in any forthcoming titles. It says a lot more about us than them.

The Bletchley Girls is published by Hodder & Stoughton (£20). Click here to buy it for £16. The Debs of Bletchley Park and Other Stories is published by Aurum (£20). Click here to buy it for £16