Winter

I am Winter that do keep

Longing safe amidst of sleep:

Who shall say if I were dead

What should be remembered?

The Woodpecker

I once a King and chief

Now am the tree-bark’s thief,

Ever ’twixt trunk and leaf

Chasing the prey.

The Lion

The Beasts that be

In wood and waste

Now sit and see

Nor ride nor haste.

Pomona

I am the ancient Apple-Queen,

As once I was so am I now.

For evermore a hope unseen,

Betwixt the blossom and the bough.

Ah, where’s the river’s hidden Gold!

And where the windy grave of Troy?

Yet come I as I came of old,

From out the heart of Summer’s joy.

William Morris’s final, 1891 collection of poetry, Poems by the Way, includes a series of engaging miniature ekphrastic verses relating to paintings or tapestries. My sample of personal favourites from these Verses for Pictures begins with Winter, which comes from a six-part sequence, Day, Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter, Night. The argument in the tiny monologue that Morris gives the personified Winter echoes the song of Orpheus in Book 12 of his once-popular epic poem, The Life and Death of Jason: “O death, that makest life so sweet … ” But, in the quatrain, it’s not simply that Winter provides the necessary contrast which, almost like a painting’s dark background, emphasises the colourful pleasures of the other seasons. Her guarantee is founded on the sense of loss. How, in her absence, she asks rhetorically, would the good things be “remembered?” The verb is extenuated over four heavy-echoing syllables. It is not emergent life, but “Longing” that Winter secures “amidst of sleep”.

The “Woodpecker” quatrain, divided into two lines of Gothic script, was woven into a tapestry designed by Morris and produced under his supervision in 1885. It illustrates the tale in Ovid’s Metamorphoses concerning King Picus, changed into a woodpecker by Circe as a punishment for rejecting her overtures. In both its precise detail and its open-endedness (the fourth unrhymed line suggests a further partnering stanza), it somehow resembles a decorated curlicue in a William Morris wallpaper pattern.

From The Forest Tapestry, The Lion offers us a more idealised image of power brought low. Morris is probably not thinking primarily of Edenic, Judeo-Christian mythology. That his lion is symbolic is clear from the assertion that such beasts neither “ride nor haste”. It seems this vignette of a life of peaceful contemplation might represent Morris’s ideal society. The creatures “sit and see”, as Morris believed all human beings would do when, released from mundane, repetitive toil, they found their true roles as artists and artisans. The competitive scramble is over. This Lion is an aesthetic Lion in a socialist Utopia, about to take up an engraving knife or paintbrush.

Pomona alludes to one of a pair of tapestry wall hangings depicting the goddesses Flora and Pomona. Like King Picus, the Roman goddess of orchards features in the Metamorphoses: in fact, to thicken the plot, she was once pursued unsuccessfully by the same king in his younger days. Again, there’s a sense of spatial neatness in the poem: as the woodpecker hunts his prey “’twixt trunk and leaf”, so the apple-queen’s promise is pledged “betwixt the blossom and the bough”.

Pomona’s liberality is ancient and immutable: her earthy gifts outlast the ephemeral glories of civilisation. Morris had unfulfilled plans to write a poem addressing the Fall of Troy: perhaps his distillation in line six of Pomona is no less evocative than an epic might have proved?

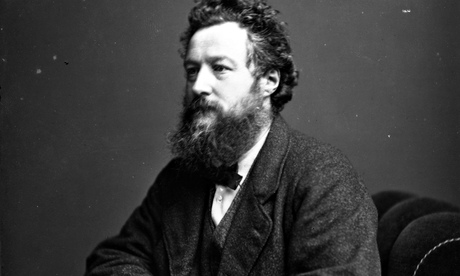

As a designer, William Morris was a revolutionary; in his politics, a radical. As a poet, he was more comfortable with the conventions of his age, although he wrote some fine, rather sombre work, some of it influenced by the Icelandic verse he translated, much of it to be found in his second collection The Earthly Paradise.

He shared convictions and preoccupations with WB Yeats, but achieved nothing comparably great in his verse. Yet in these small, aphoristic, sometimes riddle-like Verses for Pictures, with their delicate medievalist touches, he escapes the heavy-duty responsibilities of the English Victorian poet to become almost a prototype modernist. Readers new to his work might well enjoy starting here before getting down to the epic.